Andrew Coyne briefly praises the CPP before advancing a plan to (eventually) supplant it entirely:

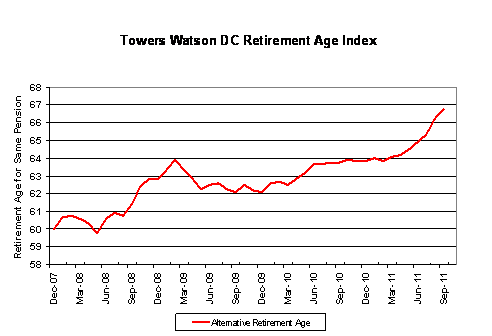

By most measures, Canada’s retirement income support system is an outstanding success. The poverty rate for Canadian seniors, with just 4.4% living below half the median income, is among the lowest in the world. The Canada Pension Plan, once careening towards insolvency, is now on a sounder footing. Millions of Canadians contribute to their Registered Retirement Savings Plans every year, with a view to replacing more of their income than the 25% covered by the CPP; Tax-Free Savings Accounts are a fast-growing alternative. For most people, then, the pension system works well. There is no evidence of a generalized pension “crisis.”

[. . .]

Suppose an additional levy were tacked onto CPP premiums. Only instead of going into the regular CPP pot, the funds would accumulate in the contributor’s own personal fund — like an RRSP, only compulsory. To avoid wasting money on management fees, funds would be invested strictly passively (ie buying the indexes), with the particular asset mix varying as the investor aged: more stocks when younger, more bonds when older.

Any increase in benefits would thus have to be fully funded; at the same time, since legal title to the funds would rest with the contributor, there would be no way politicians could raid the kitty. Moreover, with such a direct link between contributions and the size of their nest egg, contributors would be less likely to see the rise in premiums as a tax increase, and more as savings, mitigating labour market effects, at least on the supply side.

On its own, this would be vastly preferable to CPP expansion. If we liked the results, we might even think of going further. Over time, one could imagine migrating more and more of the regular CPP over to these mandatory personal accounts, allowing the CPP fund to be slowly wound down. Rather than simply expanding the CPP, the challenge of population aging presents an opportunity to reform it.