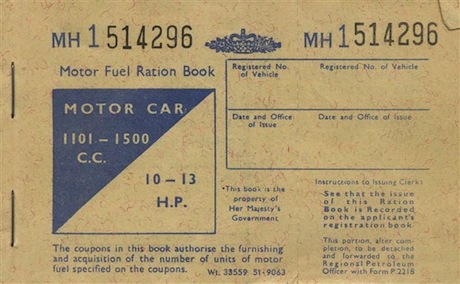

The euphoria of the New Elizabethan Age was all the more striking when set against the backdrop of the deprivation and austerity of the immediate post-war years. For many people, things had actually got worse after the war. The shortages — of food, of fuel, of housing — were such that on the first anniversary of VE Day, as Susan Cooper later recalled, “the mood of the British was one not of festivity but of bleak resignation, with a faint rebelliousness at the restrictions and looming crises that hung over them like a fog.” “We won the war,” one housewife was quoted as saying. “Why is it so much worse?” The winter of 1947 was the coldest of the century: there were shortages, and strikes, and everyone shivered; and in the spring the floods struck, closing down the London Underground, washing away the crops of thirty-one counties and pouring into thousands of homes. By the following year, rationing had fallen well below the wartime level. The average adult in 1948 was entitled to a weekly allowance of thirteen ounces of meat, one-and-a-half ounces of cheese, six ounces of butter, one ounce of cooking fat, eight ounces of sugar, two pints of milk and one egg. Even dried egg, which had been a staple of meals in wartime, had disappeared from the shops. Children at the beginning of the 1950s still wondered what their parents meant when the reminisced about eating oranges, pineapples, and chocolate; they bathed in a few inches of water, and wore cheap, threadbare clothes with “Utility” labels. It was just as well that the British prided themselves on their ability to form an orderly queue; they had plenty of opportunities to prove it. Not until July 1954 did food rationing finally come to an end.

Austerity left its mark, and many people who had scrimped and saved through the post-war years found it hard to accept the attitudes of their juniors during the long boom that followed. As one housewife later commented: “It makes you very careful and appreciate what you have got. You don’t take things for granted.” Caution, thrift, and the virtues of “making do” had become so ingrained during the long years of rationing that many people never forgot them and forever told each other, “Waste not, want not”, or reminded themselves to put things aside “for a rainy day”, or complained that their children and grandchildren did not “know the value of money.”

Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good: A history of Britain from Suez to the Beatles, 2005.

January 9, 2015

QotD: Britain in the “New Elizabethan Age” of the 1950s

April 9, 2013

Britain’s wartime rationing was the actual start of the modern welfare state

In the Telegraph, Daniel Hannan shows that the wartime coalition government led by Winston Churchill actually laid the groundwork for the post-war “creation” of the welfare state:

It wasn’t the 1945 Labour Government that created the welfare state, that Saturn which now devours its children. The real power-grab came in 1940.

With Britain’s manpower and economy commandeered for the war effort, it seemed only natural that ministers should extend their control over healthcare, education and social security. Hayek chronicled the process at first hand: his Road to Serfdom was published when Winston Churchill was still in Downing Street.

Churchill had become prime minister because he was the Conservative politician most acceptable to Labour. In essence, the wartime coalition involved a grand bargain. Churchill was allowed to prosecute the war with all the nation’s resources while Labour was given a free hand to run domestic policy.

The social-democratic dispensation which was to last, ruinously, for the next four decades — and chunks of which are rusting away even today — was created in an era of ration-books, conscription, expropriations and unprecedented spending. The state education system, the NHS, the Beveridge settlement — all were conceived at a time when it was thought unpatriotic to question an official, and when almost any complaint against the state bureaucracy could be answered with “Don’t you know there’s a war on?”

All quite true, and all quite necessary at the time. Without significant amounts of imported food, Britain could not feed its people. Even with imports, the amount of available food was subject to unpredictable fluctuations as losses at sea interrupted supply and left empty shelves in grocery stores. Although losses were relatively low early in the war (early U boats were unable to stay at sea for long periods, and German bases were a long way from most British trade routes), the writing was on the wall if the war continued for years.

To fight a totalitarian regime, Britain had to emulate some of its methods (ironically, full rationing wasn’t introduced in Germany until much later in the war). For the middle classes, this was an unwelcome intrusion of the state into private affairs, but generally accepted due to the war. For the working classes, in many cases it was actively welcomed. While the rations were small, there was the promise — and generally a fulfilled promise — that some would be made available even in the poorest areas of the country. My mother was nine when the war began, and she remembers seeing more food in the stores of Middlesbrough after rationing was introduced. After the deprivations of the Great Depression, many people in the north and in Scotland were better fed and clothed during the rationing period than they had been for nearly a decade.

Given that information, it should not be surprising that so many people voted for Labour in the 1945 elections: they’d had what they believed to be a live demonstration of the benefits of socialism for six years of war, and didn’t want to go back to the pre-1940 status quo.

July 9, 2012

The constipated British housing market

Tim Harford’s weekend column on the state of Britain’s housing market and a possible solution to the disconnect between supply and demand:

The chief obstacle to house building in the UK is the planning system, which, 65 years ago, did away with the idea that if you owned land, you could build on it, and replaced it with a system where planning permission was required. Permission to build houses is severely rationed, and such rationing can be seen clearly in the gap between the value of agricultural land without planning permission (a few thousand pounds a hectare) and the value of such land once permission has been granted (a few million).

The difficulty is that local authorities have the ability to grant planning permission but have little incentive to do so, because it tends to be unpopular with existing voters. The huge windfall from winning planning permission falls to whoever has managed to speculate on land and navigate the tangle of planning rules. These serve as nice barriers to entry for existing developers, while driving up the price of building land and so driving down the size of new homes.

Tim Leunig, chief economist at CentreForum, a think-tank, has proposed a two-part system of land auctions to get around this problem. Local authorities would buy land at auction, grant planning permission on it and then sell the land on to developers — with some strings attached, if they so choose. The profits would be enormous, and enjoyed by existing residents in the form of lower taxes or better public services. This isn’t the only way to liberalise planning, but it retains local control and democratic accountability — while dramatically increasing the incentive to develop.

Restoring a free market right to build on property you own would also be a fast solution to the diminished housing supply, but when have governments at any level willingly given up power?

July 7, 2011

March 7, 2011

Your energy consuming future

Britain is facing a very different future, from the point of energy consumption, according to Steve Holliday, CEO of National Grid:

Because of a six-fold increase in wind generation, which won’t be available when the wind doesn’t blow, “The grid is going to be a very different system in 2020, 2030,” he told BBC’s Radio 4. “We keep thinking that we want it to be there and provide power when we need it. It’s going to be much smarter than that.

“We are going to change our own behaviour and consume it when it is available and available cheaply.”

The more of your electricity that is produced from wind power, the more there will be very noticeable peaks and valleys in available electricity. Not only do you need more sources, you need over-capacity in some areas to generate sufficient power to supply to areas which are becalmed.

Under the so-called “smart grid” that the UK is developing, the government-regulated utility will be able to decide when and where power should be delivered, to ensure that it meets the highest social purpose. Governments may, for example, decide that the needs of key industries take precedence over others, or that the needs of industry trump that of residential consumers. Governments would also be able to price power prohibitively if it is used for non-essential purposes.

Perhaps it’s just the libertarian in me that finds the term “highest social purpose” to be very disturbing: just who the hell is going to be making that determination? And on what basis will the new high priests of the lightnings be making that call?

Smart grids are being developed by utilities worldwide to allow the government to control electricity use in the home, down to the individual appliance. Smart grids would monitor the consumption of each appliance and be capable of turning them off if the power is needed elsewhere.

Like the idea that someone at your local electrical board can decide that you don’t really need to run that TV set or that toaster right now? If the control freaks at the utilities manage to foist this off on us, we’ll be techno-peasants who are only allowed to run electrical devices that meet “social purpose” guidelines.