The Great War

Published 11 Apr 2025For more than three long months in 1917, Allied and German soldiers fought tooth and nail over a battlefield churned into a sea of sucking mud and shellholes by the guns. Hundreds of thousands were killed and wounded, some of them drowning in the soupy ground — for Allied gains of just a few kilometers. So why did the Battle of Passchendaele happen at all, and was it the most pointless battle of the First World War? (more…)

April 13, 2025

The Most Pointless Battle of WW1? – Passchendaele 1917

October 8, 2023

The Grave of Canada’s Greatest General: Sir Arthur Currie

OTD Military History

Published 23 Jun 2023The grave of General Sir Arthur Currie in Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal, Quebec. Arthur Currie was the commander of the Canadian Corps from June 1917 to the end of World War 1. Appointed as the Principal and Vice-Chancellor of McGill University in 1920, he held that position until his death in 1933.

(more…)

July 1, 2023

QotD: The ever-increasing size and number of artillery pieces in WW1 trench battles

Because the generals on the attacking side – and it is worth remembering that Germany, Austria-Hungary, Britain, France and Italy all took their turns being the attacker on the narrower Western and Italian fronts defined by continuous unbroken trench-lines (the Eastern Front was somewhat more open) – were actively looking for ways out of the trench stalemate. We’ve already discussed one effort to get out, poison gas, and why it didn’t succeed. But there was a more immediate solution: after all, every field manual said the solution to weakening infantry positions on the field was artillery. Sure, trenches and dugouts made infantry resistant to artillery, but they didn’t make them immune to it. So what if we used more artillery?

So by the Second Battle of Artois (May, 1915), the barrage was four days long and included 293 heavy guns and 1,075 lighter pieces. At Verdun (February, 1916) the Germans brought in 1,201 guns, mostly heavy indirect fire artillery (of which the Germans had more than the French) with a shifting barrage that expected to fire 2 million shells in the first six days and 4 million during the first 18 days. At the Somme (1916) the British barrage lasted from the 24th of June to the attack on July 1 (so a seven-day barrage); a shorter barrage was proposed but could not be managed because the British didn’t have enough guns to throw enough shells in the shorter time frame. A longer barrage was also out: the British didn’t have the shells for it. By Passchendaele (1917) the British were deploying some 3,000 artillery pieces; one for every 15 yards of frontage they were attacking.

These efforts didn’t merely get to be more, but also more complex. It was recognized that if the infantry could start their advance while the shells were still falling, that would give them an advantage in the race to the parapet. The solution was the “creeping” barrage which slowly lifted, moving further towards the enemy’s rear. These could be run by carefully planned time-table (but disaster might strike if the infantry moved too slow or the barrage lifted too early) or, if you could guarantee observation by aircraft, be lifted based on your own movements (in as much as your aircraft pilots, with their MK1 eyeballs, could tell what was happening below them). […]

I find that most casual students of military history assume that these barrages generally failed. I suspect this has a lot to do with how certain attacks with ineffective barrages (e.g. the Somme generally, the ANZAC Corps’ attack at Passchendaele) have ended up as emblematic of the entire war (and in some cases, nationality-defining events) in the English-language discussion. And absolutely, sometimes the barrages just failed and attacks were stopped cold with terrible losses. But rather more frequently, the barrages worked: they inflicted tremendous casualties on defenders and allowed the attackers to win the race to the parapet which in turn meant the remaining defenders were likely to be swiftly grenaded or bayoneted. This is part of why WWI commanders continued to believe that they were “on the verge of a breakthrough”, that each attack had come so close, because initially there were often promising gains. They were wrong, of course, about being that close, but opening attacks regularly overran the initial enemy positions. Even the worst debacles of the war, like at the Somme, generally did so.

And at this point, you may be wondering if you’d been lied to, because you were always told this was a war where advances where measured in feet and meters instead of miles or kilometers and how can that be if initial attacks generally did, in fact, overrun the forward enemy positions? I’ll push this even further – typically, in the initial phases of these battles (the first few days) the casualty rates between attacker and defender were close to even, or favored the attacker. This is of course connected to the fact that the leading cause of battle deaths in the war was not rifle fire, machine guns, grenades, bayonets but in fact artillery fire and the attacker was the one blasting fixed positions with literal tons of artillery fire. So what is going on?

Because both sides quickly figured out that their forward positions were badly exposed to artillery barrages and began designing defenses in depth, with rear positions well out of the reach of all but the largest enemy artillery. For instance, most of the so-called “Hindenburg Line” (the Germans called it the Siegfriedstellung or “Siegfried Position”) was set in multiple lines […] The plan consisted of a thin initially defense which was assumed to fall in the event of an attack, but still featured channels made by heavy barbed wire and machine guns designed to inflict maximum casualties on an advancing force (and be dangerous enough to require the artillery barrage and planned assault). Then behind that was more open ground and then a second line of trenches, this time much more solid, with communications trenches cutting vertically and the battle positions horizontally, enabling reserves to be brought up through those trenches without being exposed to fire. Finally the reserves themselves were in a third line of trenches even further back, well outside of the enemy’s barrage (or indeed the range of all but their heaviest guns). Of course while your artillery is in the back, out of range of the enemy artillery, the enemy infantry is attacking into your artillery range. This keeps your artillery from being disabled into the initial barrage (you hope) so that it can be brought into action for the counter-attack.

And now the enemy of the attacker is friction (as we’ve discussed before with defense in depth). If everything possible goes right, you open with the barrage, your infantry sweeps forward, the creeping barrage lifts and you win the race to the parapet. The forward enemy defenders are either blasted apart by the barrage or butchered in their holes by your gas, grenades and bayonets. Great! Now you need to then attack again out of those enemy positions to get to the next line, but your forces are disorganized and disoriented, your troops are tired and your supplies, reinforcements and artillery (including many heavy guns that weigh many tons and shoot shells that also weigh 100+lbs a pop) have to get to you through the terrain the barrage created […]

So rapidly the power of your initial attack runs out. And then the counter-attacks, as inevitable as the rising sun, start. Your opponents can shell you from nice, prepared positions, while your artillery now has to move forward to support you. Their troops can ride railways to staging posts close to the front lines, advance through well-maintained communications trenches directly to you, while your troops have to advance over open group, under artillery fire, in order to support you. The brutal calculus begins to take its toll, you lose ground and the casualty ratios swings in favor of the “defender” (who to be clear, is now attacking positions he once held). Eventually your footholds are lost and both sides end up more or less where they started, minus a few hundreds or thousands of dead. This – not the popular image – this is the stalemate: the attacker frequently wins tactically, but operational conditions make it impossible to make victory stick.

The brutal irony of this “defensive” stalemate is that at any given moment in a battle that might last months and swing from offensive to defensive and back again that casualties typically favored the side which was attacking at any given moment. More ironic yet, the problem here is that the artillery itself is digging the hole you cannot climb out of, because it is the barrage that tears up the landscape, obliterating roads, making movement and communication nearly impossible for the attacker (but not for the defender). But without the barrage, there’s no way to suppress enemy artillery and machine guns to make it possible to cross no man’s land. Even with tanks, an attack without supporting artillery is suicide; enemy artillery will calmly knock out your tanks (which are quite slow; this is in 1918, not 1939).

The problem, for the attacker and the defender isn’t machine guns, it is artillery: the artillery that makes assaults possible in the first place makes actual victory – breaking through the enemy and restoring maneuver – impossible.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part I: The Trench Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-17.

December 30, 2021

The Story Of Sir Arthur Currie: From Gunner To General | The Great War With Norm Christie | Timeline

Timeline – World History Documentaries

Published 28 Dec 2021Military historian Norm Christie presents a four-part series examining the First World War from a Canadian perspective. As he begins his journey through the historic battlefields of France and Belgium, Christie focuses on the career of General Sir Arthur Currie, a soldier who rose through the ranks from humble gunner in 1897 to lead the Canadian Corps to several victories during the conflict which began in 1914.

It’s like Netflix for history… Sign up to History Hit, the world’s best history documentary service and get 50% off using the code ‘TIMELINE’ http://bit.ly/3a7ambu

You can find more from us on:

https://www.instagram.com/timelineWH

Any queries, please contact owned-enquiries@littledotstudios.com

Note: The original YouTube title said “from Gunman to General”. Perhaps in British usage, “gunman” is a variant of “gunner” (an artilleryman), but in Canadian usage the word “gunman” almost invariably means armed criminal or terrorist, and while Sir Arthur’s career had its difficulties, he was never a criminal.

March 13, 2020

“The Price of a Mile” – The Battle of Passchendaele – Sabaton History 058 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 12 Mar 2020So tell me what’s the price of a mile? The Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 is often remembered as a dismal and dreadful campaign. Fighting over endless mud, waterlogged shell-holes and unrecognizable, bombed out ground, the battle became a slog where everybody was just miserable. Hundreds of thousands of men became casualties for the advance of a handful of miles.

The Art of War online: https://sites.ualberta.ca/~enoch/Read… [PDF]

Support Sabaton History on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sabatonhistory

Listen to “Price of a Mile” on the album The Art of War:

CD: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarStore

Spotify: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarSpotify

Apple Music: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarAppleMusic

iTunes: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWariTunes

Amazon: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarAmz

Google Play: http://bit.ly/TheArtOfWarGooglePlayCheck out the trailer for Sabaton’s new album The Great War right here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCZP1…

Listen to Sabaton on Spotify: http://smarturl.it/SabatonSpotify

Official Sabaton Merchandise Shop: http://bit.ly/SabatonOfficialShopHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard and Wieke Kapteijns

Produced by: Pär Sundström, Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Executive Producers: Pär Sundström, Joakim Broden, Tomas Sunmo, Indy Neidell, Astrid Deinhard, and Spartacus Olsson

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Karolina Kosmowska

Sound Editing by: Marek Kaminski

Maps by: Eastory – https://www.youtube.com/c/eastoryArchive by: Reuters/Screenocean https://www.screenocean.com

Music by Sabaton.Sources:

– Imperial War Museum: Q 20705;Q 45462;Q 5989;6Q 2890;Q 3117 Q 3008;Q 2712;Q 23779;Q 7806;Q 5937;Q 5726;Q 2902;Q 2713;Q 57299;Q 57247;Q 45390;Q 51569;Q 1426;Q 540;Q 17868;Q 50237;Q 47725;Q 45382;Q 2639;Q 29088;Q 42251;Q 5714;Q 2868;Q 5938;Q_005935;Q 2625;Q 5723;Q 2627;Q 29090;Q 52862;Q 88098;Q 88017;Q 2706;Q 5936;Q 5904;Q 5940;Q 5941;Q 5902;Q 47741;Q 3001;Q 5947;Q 6458;Q 3252;Q 29088;Q 5767;Q 45461;Q 42251;Q 2682;Q 20705;Q 6346;Q 6223;Q 11688;Q 2708.;Q 47719;Q 3103;Q 2679;;Q 2640;Q 2858;Q 2735;Q 2707;Q 2757;Q 5901;Q 3006.;Q 5904;Q 5928;Q 3104;Q5903;Q 29089;Q 5865;Q 11668;Q 3002;Q 2978;Q 3121;Q5706;Q 47741;Q 2755;Q 55558;Q 3012;Q 5874;Q 5888;Q 7806;Q 6327;Q 54408;Q 2866;Q 56567;Q 6047;Q 6049;Q 3252; 3140;Q 2868;Q 61034;Q 42250;Q 3025;Q 7814.;Q 2893;Q 2737;E00777;Q 3029;Q 2763;Q 5773;Q 2756;Q 47741;Q 45369;Q 2707;Q 6327;Q 5902.;Q 3006;Q 5871;Q 5733; CO 1757;CO 2241;CO 1757;CO 2252;CO 2241;CO 1757;CO 2246;CO 2252;CO 1763;CO 2241; E(AUS) 941;(E(AUS) 719);E(AUS) 1233.;(E(AUS) 719),

– Art IWM: ART 1921; ART 1150,

– The Australian War Memorial: E00693; E04678; E01912; E00874; E00807; E00874; E01229; A02653; E00927

– National Army Museum: 1952-01-33-55-391; 1985-04-48-412; 2001-02-256-96;1997-12-75-81; 2010-01-56-40; 1994-12-31-1; 1978-11-157-24-36;

1965-10-209-27; 1972-08-67-1-40; 1917-07-31,

– Canadian War Museum: CWM 19930013-511;CWM 19890222-001;CWM 19930013-464;CWM 19930013-511;CWM 19710261-0093.;

165-BO-1503,

– Library and Archives Canada: 040139An OnLion Entertainment GmbH and Raging Beaver Publishing AB co-Production.

© Raging Beaver Publishing AB, 2019 – all rights reserved.

November 17, 2017

The End Of Passchendaele – Fighting in Petrograd I THE GREAT WAR Week 173

The Great War

Published on 16 Nov 2017The Anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia are trying to fight back last week’s revolution. The Battle of Passchendaele ends after 3 months of fighting and at least 500,000 casualties on both sides. The British are still advancing on Jerusalem and the Italians set up defences behind the Piave river.

November 10, 2017

The Russian October Revolution 1917 I THE GREAT WAR Week 172

The Great War

Published on 9 Nov 2017After the turmoil of the past weeks in Petrograd, the Soviets and the Red Guards seize the opportunity and topple the provisional government under Alexander Kerensky. Their first goal is to pull out of the war. The Italians were still in full retreat during the Battle of Caporetto and the British Army was still advancing in Palestine.

November 6, 2017

The end of the battle of Passchendaele, 1917

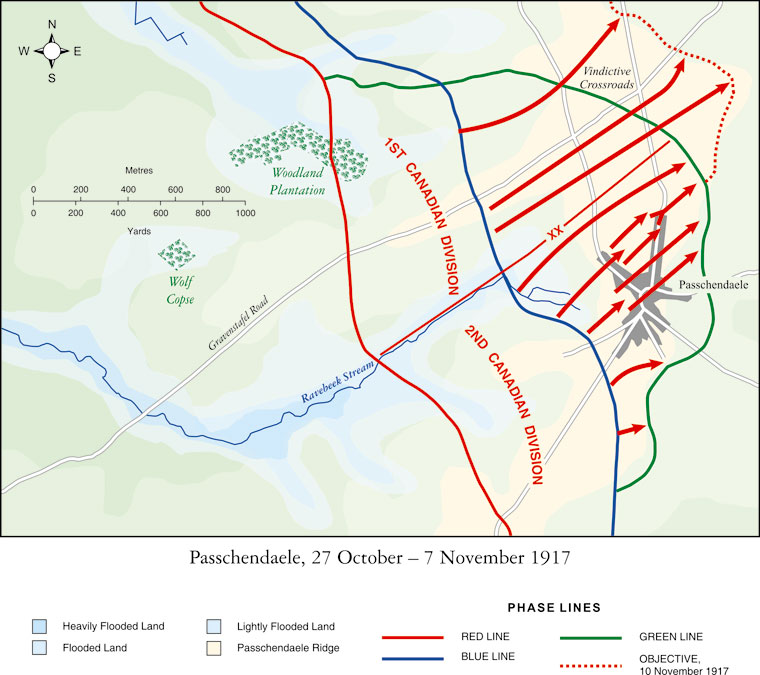

The Canadian Corps under Lieutenant General Arthur Currie began the final phase of the battle on 6 November, 1917:

By 6 November, the Canadians were prepared to advance upon the Green Line. The final objective was to capture the high ground north of the town and to secure positions on the eastern side of Passchendaele Ridge. Again, according to Major Robert Massie: “The third attack … was the day when the First and Second Divisions took Passchendaele itself. On this occasion, the attack went off the most smoothly of any of the three. They had fair ground to go over, and especially those that went into Passchendaele itself had pretty fair going, and the objectives were reached on time.”

After early hand-to-hand fighting, the 2nd Division easily occupied Passchendaele just three hours after commencement of the attack at 0600 hours. The 1st Division, however, found itself in some trouble when one company of the 3rd Battalion became cut off and was stranded in a bog. When this situation eventually righted itself, the 1st Division continued toward its objectives. Well-camouflaged tunnels at Moseelmarkt provided an opportunity for the enemy to counterattack, but they were fended off by the Canadians. By the end of the day, the Canadian Corps was firmly in control of both Passchendaele and the ridge.

The final Canadian action at Passchendaele commenced at 0605 hours on 10 November 1917. Sir Arthur Currie used the opportunity to make adjustments to the line, strengthening his defensive positions. Robert Massie summed up the thoughts of many participating Canadians as follows: “What those men did at Passchendaele was beyond praise. There was no protection in that land. They could not get into the trenches which were full of mud, and you would see two or three of them huddled together during the night, lying on ground that was pure mud, without protection of any kind, and then going forward the next morning and cleaning up their job.”

The Canadians had done the impossible. After just 14 days of combat, they had driven the German army out of Passchendaele and off the ridge. There was almost nothing left of the village to hold. Altogether, the Canadian Corps had fired a total of 1,453,056 shells, containing 40,908 tons of high explosive. Aerial photography verified approximately one million shell holes in a one square mile area. The human cost was even greater. Casualties on the British side totalled over 310,000, including approximately 36,500 Australians and 3596 New Zealanders. German casualties totalled 260,000 troops.

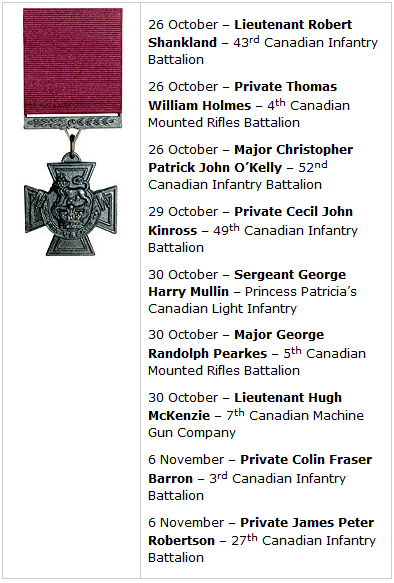

For the Canadians, Currie’s words were prophetic. He had told Haig it would cost Canada 16,000 casualties to take Passchendaele – and, in truth, the final total was 15,654, many of whom were killed. One thousand Canadian bodies were never recovered, trapped forever in the mud of Flanders. Nine Canadians won the Victoria Cross during the battles for Passchendaele. While the human cost had been terrible: “Nevertheless, the competence, confidence, and maturity began in 1915 at Ypres a short distance away, and at Vimy Ridge earlier that spring, again confirmed the reputation of the Canadian Corps as the finest fighting formation on the Western Front.” So wrote esteemed Professor of History Doctor Ronald Haycock at the Royal Military College of Canada for The Oxford Companion to Canadian History in 2004.

Haig proved to be true to his word. By 14 November 1917, the Canadians had been returned to the relative quiet of the Vimy sector. They had not been asked to hold what it had cost them so much to take. However, by March 1918, all the gains made by Canada at Passchendaele would be lost in the German spring offensive known as Operation Michael.

General Sir David Watson praised the Canadian effort: “It need hardly be a matter of surprise that the Canadians by this time had the reputation of being the best shock troops in the Allied Armies. They had been pitted against the select guards and shock troops of Germany and the Canadian superiority was proven beyond question. They had the physique, the stamina, the initiative, the confidence between officers and men (so frequently of equal standing in civilian life) and happened to have the opportunity.”

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was even clearer when it came to the Canadians: “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line they prepared for the worst.”

November 5, 2017

Breakthroughs and Setbacks – Fall 1917 I THE GREAT WAR Summary Part 11

The Great War

Published on 4 Nov 2017The Battle of Passchendaele begins on the Western Front, whilst the climate grows steadily more unstable in Russia, where General Kornilov hopes to seize power. Operation Albion is launched by Germany in the Northeast, and the French enjoy some successes, including at Malmaison. The tide is turned in the Battle of Caporetto. The death toll climbs ever higher, in yet another dark period of the Great War. We cover all this and more in our recap of Fall 1917.

November 3, 2017

Battle of Beersheba – Canadian Frustration – Balfour Declaration I THE GREAT WAR Week 171

The Great War

Published on 2 Nov 2017On the Western Front this week, the Canadians under Sir Arthur Currie attempt to advance once more, whilst Haig remains optimistic about an imminent breakthrough. Following Caporetto, the Italian retreat continues, whilst the British Army enjoys success on the Palestine Front, with a little help from mounted ANZAC troops. With Lenin’s return, the revolution looms over the Russian capital, whilst the Balfour Declaration is issued in Britain.

October 27, 2017

The Battle of La Malmaison – Breakthrough at Caporetto I THE GREAT WAR Week 170

The Great War

Published on 26 Oct 2017The French score a morale boosting victory over the German at La Malmaison, but the Canadians were not so successful elsewhere on the Western Front. Whilst the Germans continue on through the Estonian Archipelago and onto the Russian mainland, the 12th Battle of the Isonzo takes place on the Italian Front. Unlike the 11 battles that came before it, this one was initiated by the Central Powers and was their biggest breakthrough yet on that front.

October 24, 2017

German Defensive Strategy and Tactics At Passchendaele I THE GREAT WAR Special

The Great War

Published on 23 Oct 2017Hindenburg Line Poster: http://bit.ly/HindenburgLinePoster

The Hindenburg Line, which was developed in early 1917, was designed to have depth and flexibility. Pillboxes, bunkers and machine gun nests all played vital roles in the system, as did the counter-attacking Eingreiftruppen. Since its conception, it had been effective when used properly, but Passchendaele would be where the Siegfriedstellung would face its toughest test yet. Allied superiority in artillery and aircraft, unrelenting bad weather and exhausted soldiers all put a huge strain on the German defence system, but would they be its undoing?

October 20, 2017

Operation Albion Concludes – Allied Failures In Belgium I THE GREAT WAR Week 169

The Great War

Published on 19 Oct 2017100 years ago this week, Operation Albion comes to a successful end for the Germans, as revolution is on the horizon in Russia. The Allies aren’t faring quite so well on the Western Front, where the weather continues to worsen and the death toll climbs ever higher. Haig believes a breakthrough is imminent and German morale is tested. The stalemate continues, but sooner or later the Battle of Passchendaele must come to an end.

October 13, 2017

Operation Albion – Passchendaele Drowns In Mud I THE GREAT WAR Week 168

The Great War

Published on 12 Oct 2017The situation for the German Army on the Western Front looks grim, but in the East they have the upper hand and this week begin to put pressure on the Russians in Operation Albion – an amphibious landing operation in the Estonian archipelago. At the same time, the battlefield at Passchendaele is turning into a muddy swamp.

October 6, 2017

Sabotage In The Desert – Battle of Broodseinde I THE GREAT WAR Week 167

The Great War

Published on 5 Oct 2017While the regular British forces were advancing towards Jerusalem and Baghdad, T.E. Lawrence and the Arab Revolt were causing havoc behind the lines. This week 100 years ago, they were continuing to attack the important Hejaz railway which was one of the vital supply routes for the Ottoman Army. On October 4, the Battle of Broodseinde was fought near Ypres and the costly British victory there caused real headaches for German general Erich Ludendorff.