Dita von Teese: I of all people told someone not to “romance the past” the other night. But not everthing was better back then, that’s a fact!

October 5, 2009

September 15, 2009

QotD: Generational obsolescence

What I find amusing is how some believe that the death of civility is a new development. It started with Joe Wilson and was compounded by Serena Williams. Civility has been chained to a rock getting its liver picked out by buzzards since the golden children of the Greatest Generation were encouraged to let their freak flag fly, to use a horrid phrase.

[. . .]

I’ve always thought it’s imperative to stay engaged with your times until your time, singular, is up. Otherwise your sense of the world calcifies, and your worst impressions become your default opinion. The glories of the imagined past become a means of self-admiration, because you were not only lucky enough to be there but smart enough to get it. Kids today, they don’t. Perhaps growing up in the 70s kept me from idealizing my own past; the culture was all gimcrack glitz and second-hand hippie shite before the jams were well and truly kicked out by the anti-sloth movements of the late seventies and early 80s. They were musical and political; the former was all over the road and the latter emotional and naive, but I think they were the first attempts to wrest control of the social narrative from the early boomers, and as such were derided with the smooth weary conceits you’d expect from the generation that remade the world and expected the rest of us to line up and lay laurel wreaths at their sandaled feet.

Then the rise of internet culture saved the late boomers and Gen Xers from cultural obsolescence, because it was no longer necessarily to participate in any of the usual events to be up to the moment. On the internet anyone can be about 26 years old.

James Lileks, The Bleat, 2009-09-15

July 25, 2009

A blast from my past

I was reading Charles Stross’s blog the other day, and noticed that he’d nicely compiled all his “How I got here in the end” blog entries into a single post. I’d not read the whole thing, so a quick bookmark and I was off to other things. Today, while going back to the bookmark, I discovered that we may have crossed paths in our respective previous lives:

I spent nearly three and a half years working on technical documentation for a UNIX vendor during the early 90s. Along the way, I learned Perl (against orders), accidentally provoked the invention of the

robots.txtfile, was the token Departmental Hippie, and finally jumped ship when the company ran aground on the jagged rocky reefs of the Dilbert Continent. At one time, that particular company was an extremely cool place to work. But today, it lingers on in popular memories only because of the hideous legacy of it’s initials … SCO.SCO was not then the brain-eating zombie of the UNIX world, odd though this may seem to young ‘uns who’ve grown up with Linux. Back in the late eighties and early nineties, SCO (then known more commonly as the Santa Cruz Operation) was a real UNIX company. Started by a father-son team, Larry and Doug Michels, SCO initially did UNIX device driver work. Then, around 1985, Microsoft made a huge mistake. Back in those days, MS developed code for multiple operating systems. Some time before then, they’d acquired the rights to Xenix, a fork of AT&T UNIX Version 7. SCO did most of the heavy lifting on porting Xenix to new platforms; and so, when Microsoft decided Xenix wasn’t central to their business any more, SCO bought the rights (in return for a minority shareholding).

SCO is one of the stops on my resumé that I rarely call attention to, as it was an unhappy and eventually unpleasant stop along the way. Charles says “late 1991”, so perhaps we didn’t actually meet . . . I visited the SCO Watford office in August.

Still, I’d like to think that I met one of my favourite authors before he became famous . . .

Later on in that mega-post he says:

During this process I discovered several things about myself. I do not respond well to micro-managing. I especially do not respond well to being micro-managed on a highly technical task by a journalism graduate. Also, I’m a lousy proofreader. Did I say lousy? I meant lousy.

Dude. You want to talk micro-managed? My (Toronto-based) manager wanted twice-daily meetings where I needed to show my progress since the last meeting. I got so paranoid about “showing progress” that I stopped writing altogether, just showing a list of emails I’d been involved in since the last 4-hourly meeting occurred . . .

Do I need to say that my employment at SCO didn’t last much more than a few months after my visit to the Watford office?

Reading further in Charlie’s memoirs:

Here is an example of a Terminally Bad Sign for any organization in the computer business:

… When you discover that your line manager’s recreational reading is the 1980 edition of the IBM Staff Handbook.

Oddly enough, I had a few co-op work terms with IBM in the mid-to-late 1980’s. There were few books that could strike fear in the hearts of technology sector workers like official IBM publications. My very first official IBM staff meeting had the head of R&D in IBM Canada saying things like “There is business out there that we’re not getting. Business that GOD HIMSELF wanted us to have!” For some reason, I thought he was making a joke. I laughed out loud. My IBM career didn’t exactly go upwards from there . . .

July 20, 2009

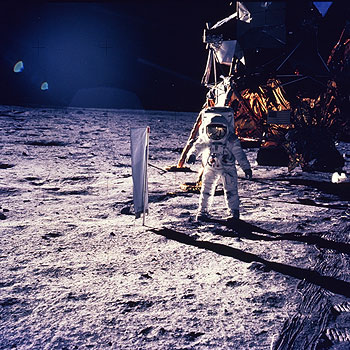

That’s one small miscue for a man, one giant leap for Mankind

It was 40 years ago:

Armstrong and fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin left the Apollo 11 command module (piloted by Michael Collins) in orbit and performed a landing in the lunar module Eagle. At 4:18 p.m. EDT, Armstrong announced to a watching and waiting world that “The Eagle has landed.”

Six-and-a-half hours later, he stepped onto the powdery surface with the words, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin soon followed Armstrong down the ladder to become the second man to stand on the moon.

The mission was by no means a slam dunk. There was real fear that once on the lunar surface the astronauts might end up marooned and beyond rescue. In fact, President Nixon had a condolence speech ready to go in the event things turned out badly.

Nostalgia is an interesting phenomenon . . . the very term “President Nixon” is pried out of deep archaeological layers of memory, yet the first moon landing still seems fresh and no-longer-new but still somehow “recent”.

If you’re still eager for more, Wired has a convenient round-up of Apollo 11-related sites and events.

July 15, 2009

It’s been 40 years . . . why haven’t we gone back?

On July 20th, it will have been 40 years since many of us clustered around our tiny black-and-white televisions, watching the first moon landing (or for those of you of conspiracist leanings, a really convincing sound stage in Area 51). Why, after all this time, haven’t we gone further? Why, for that matter, have we not been back to the moon for over a generation? Ronald Bailey explains the real reason:

The Apollo moon landings have often been compared to the explorations of Christopher Columbus and the Lewis and Clark expedition to Oregon. For example, on the 20th anniversary of the first moon landing, President George H.W. Bush declared, “From the voyages of Columbus to the Oregon Trail to the journey to the Moon itself: history proves that we have never lost by pressing the limits of our frontiers.”

But what boosters of the moon expeditions overlook is that the motive for pressing the limits of our frontiers in those cases was chiefly profit. In his report from his first voyage, Columbus predicted that his explorations would result in “vast commerce and great profit.” The extension of commerce was also the chief justification that President Thomas Jefferson gave in his secret message to Congress requesting $2,500 to fund what would become the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Forty years later, as we bask in the waning prestige that the Apollo missions earned our country, we must keep in mind that humanity will some day colonize the moon and other parts of the solar system, but only when it becomes profitable to do so.

Back in 1969, my friend Alan Fairfield and I sat in fascination (at least in the golden memory, they do . . . we were nine: I doubt that we paid as much attention to the broadcast as his mother thought we should). Mrs. Fairfield told us that we’d be able to go to the moon ourselves by the time we were grown up. It didn’t turn out that way, and at the current rate of progress, it may not turn out that way for my grandkids.

But I still hope, one day . . .

(Cross-posted to the old blog, http://bolditalic.com/quotulatiousness_archive/005583.html.)