Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 16 Aug 2022

(more…)

January 10, 2023

Catherine the Great & the Volga Germans

December 16, 2021

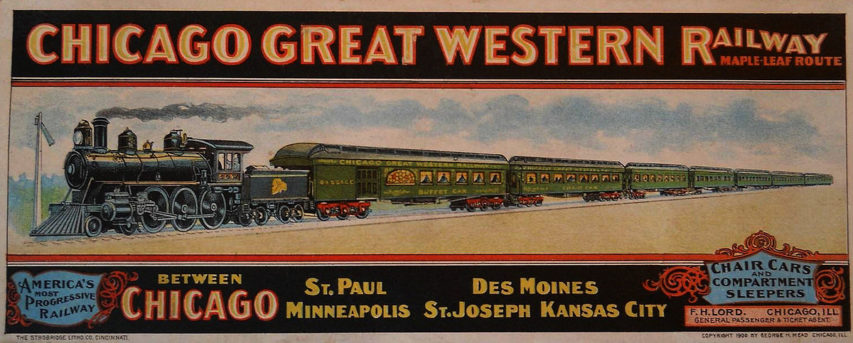

Fallen Flag — the Chicago Great Western Railroad

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

The Panic of 1907 ended Stickney’s control of the railway and it ended up in the hands of J.P. Morgan:

Even though Stickney had imaginatively assembled a Midwestern trunk line, he ultimately lost his railroad. The brief but severe Bankers’ Panic of 1907 threw CGW into receivership, a fate the company had avoided during the much more severe Panic of 1893. The nation’s financial wizard, J.P. Morgan, took control, and in 1909 a reorganized Chicago Great Western Railroad made its debut. Morgan wisely placed Samuel Morse Felton in charge, because the new president excelled as a railroad manager. His greatest triumph before joining the Great Western had been to turn the Chicago & Alton into a profitable property.

[…]

The Felton years in Chicago Great Western railroad history resulted in a rehabilitated physical plant. Changes in rolling stock caught the attention of thousands of on-line residents. In 1910, for example, CGW purchased 10 Baldwin 2-6-6-2 Mallets (“Snakes”, as employees called them), and the road’s own shop forces at Oelwein, Iowa, rebuilt three F-3 class 2-6-2s (CGW had 95 total Prairie types) into three more 2-6-6-2s. Unfortunately, these giants did not work out, and in 1916 the Baldwins were sold to the Clinchfield and the homebuilds were rebuilt into 4-6-2s. In the Mallets’ place appeared reliable yet powerful 2-8-2s, of which CGW owned 35.

The railroad became a leader in the use of gasoline and later diesel motive power. Before World War I CGW assembled a small fleet of McKeen motor cars, knife-nosed “wind-splitters” that replaced steam-powered branchline and local trains. Its 1924 gas-electric car M-300 was the first unit of any type sold by the Electro-Motive Co., and it helped replace steam on trains 3 and 4 on the 509-mile Chicago–Omaha run. In 1929 CGW remodeled three McKeens to make up a deluxe gas-electric train, the Minneapolis–Rochester (Minn.) Blue Bird. CGW was mostly satisfied with its pioneering internal-combustion equipment.

1906 advertising blotter for the Chicago Great Western Railroad’s passenger trains.

Wikimedia Commons.

CGW’s independent life came to an end in the same era as a lot of small to medium sized railways disappeared into corporate mergers, take-overs, or bankruptcy:

Being a small road in an era when competitors were expanding through mergers led to the corporate demise of the CGW. Saying that shareholders “must be protected”, the board sought a partner. Although the expectation was union with KCS or perhaps the Soo Line, the aggressive Chicago & North Western, headed by resourceful Ben W. Heineman, made an acceptable proposal, and in 1968 Chicago Great Western Railroad history ended with it becoming a Fallen Flag.

C&NW operated CGW switchers and F units for a short time, and assimilated Great Western’s only second generation diesels — eight GP30s and nine SD40s, all painted in the final solid “Deramus red” seen also on KCS and Katy — into the yellow fleet.

Although for a short time much of the former Great Western maintained its identity as C&NW’s Missouri Division, that operating organization ended and its lines started to disappear. By the 1980s much of the trackage had been retired, and at the start of the 21st century only about 145 miles remained. Survivors include portions of the main lines in Iowa (Mason City to the Fort Dodge area; Oelwein–Waterloo; and a leg into Council Bluffs); the Cannon Falls (Minn.) branch; and terminal trackage around South St. Paul, Minn., and just west of Chicago.

December 5, 2019

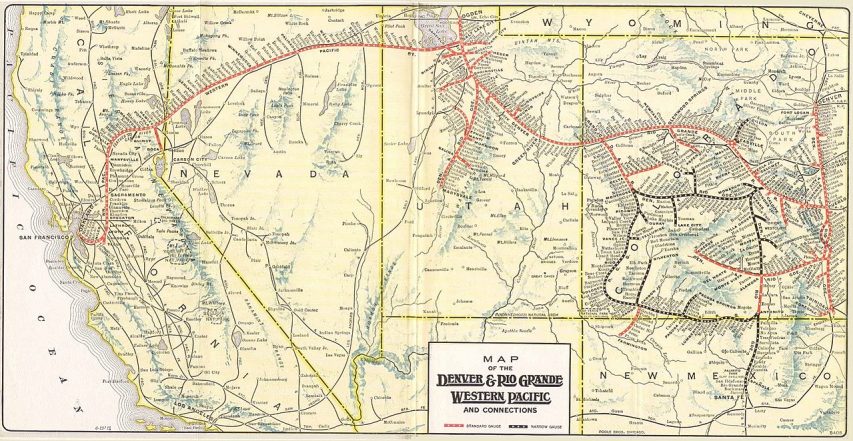

Fallen flag – the Denver & Rio Grande Western

The origins of the Denver & Rio Grande Western by Mark Hemphill for Trains magazine:

1914 route map of the Denver & Rio Grande Western and Western Pacific railroads.

Map via Wikimedia Commons

In the American tradition, a railroad is conceived by noble men for noble purposes: to develop a nation, or to connect small villages to the big city. The Denver & Rio Grande of 1870 was not that railroad. Much later, however, it came to serve an admirable public purpose, earn the appreciation of its shippers and passengers, and return a substantial profit.

The Rio Grande was conceived by former Union Brig. Gen. William Jackson Palmer. As surveyor of the Kansas Pacific (later in Union Pacific’s realm), Palmer saw the profit possibilities if you got there first and tied up the real estate. Palmer, apparently connecting dots on a map to appeal to British and Dutch investors, proposed the Denver & Rio Grande Railway to run south from Denver via El Paso, Texas, to Mexico City. There was no trade, nor prospect for such, between the two end points, but the proposal did attract sufficient capital to finish the first 75 miles to Colorado Springs in 1871.

William Jackson Palmer 1836-1909, founder of Colorado Springs, Colorado, builder of several railroads including the D&RGW.

Photograph circa 1870, photographer unknown, via Wikimedia Commons.Narrow-gauge origins

Palmer chose 3-foot gauge to save money, assessing that the real value lay in the real estate, not in railroad operation. At each new terminal, Palmer’s men corralled the land, then located the depot, profiting through a side company on land sales. Construction continued fitfully to Trinidad, Colo., 210 miles from Denver, by 1878. Above Trinidad, on the ascent to Raton Pass, Palmer’s engineers collided with the Santa Fe’s, who were building toward California. Realizing that a roundabout narrow-gauge competing with a point-to-point standard-gauge would serve neither the fare box nor the next prospectus, Palmer changed course, making D&RG a supply line to the gold and silver bonanzas blossoming all over Colorado and Utah. Thus the Rio Grande would look west, not south, and would plumb so many canyons in search of mineral wealth that it was a surprise to find one without its rails.Turning west at Pueblo, Colo., and outfighting the Santa Fe for the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River — where there truly was room for only one track — D&RG entered Leadville, Colorado’s first world-class mining bonanza, in 1880. Three years later, it completed a Denver–Salt Lake City main line west from Salida, Colo., via Marshall Pass and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. The last-spike ceremony in the desert west of Green River, Utah, was low-key, lest anyone closely examine this rough, circuitous, and glacially slow “transcontinental.” Almost as an afterthought, D&RG added a third, standard-gauge rail from Denver to Pueblo, acknowledgment that once paralleled by a standard-gauge competitor, narrow-gauge was a death sentence.

New owners, new purpose

Palmer then began to exit. The company went bust, twice, in rapid succession. The new investors repurposed the railroad again. Instead of transient gold and silver, the new salvation would be coal. Thick bituminous seams in the Walsenburg-Trinidad field fed beehive coke ovens of a new steel mill near Pueblo and heated much of eastern Colorado and western Kansas and Nebraska.

August 2, 2014

The Burlington “Zephyr” in 1939

Visit the Retronaut for three more photos in this series. Wikipedia says:

The Pioneer Zephyr is a diesel-powered railroad train formed of railroad cars permanently articulated together with Jacobs bogies, built by the Budd Company in 1934 for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), commonly known as the Burlington. The train featured extensive use of stainless steel, was originally named the Zephyr, and was meant as a promotional tool to advertise passenger rail service in the United States. The construction included innovations such as shotwelding (a specialized type of spot welding) to join the stainless steel, and articulation to reduce its weight.

On May 26, 1934, it set a speed record for travel between Denver, Colorado, and Chicago, Illinois, when it made a 1,015-mile (1,633 km) non-stop “Dawn-to-Dusk” dash in 13 hours 5 minutes at an average speed of 77 mph (124 km/h). For one section of the run it reached a speed of 112.5 mph (181 km/h), just short of the then US land speed record of 115 mph (185 km/h). The historic dash inspired a 1934 film and the train’s nickname, “The Silver Streak”.

The train entered regular revenue service on November 11, 1934, between Kansas City, Missouri; Omaha, Nebraska; and Lincoln, Nebraska. It operated this and other routes until its retirement in 1960, when it was donated to Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, where it remains on public display. The train is generally regarded as the first successful streamliner on American railroads.

September 16, 2012

Nebraska: same penalty for manslaughter and for operating a business without a license

Nebraska sure is harsh on people who operate unlicensed businesses. Or they’re really soft on those who commit manslaughter:

The libertarian public-interest law firm Institute for Justice reports on one of the most insane, inane, and profane prosecutions in all-time memory.

Karen Hough is a long-time practitioner of “equine massage,” which supposedly is beneficial in all sorts of ways to the animals in question.

[. . .]

A few weeks later, she received a letter from Nebraska’s Department of Health and Human Services ordering her to “cease and desist” from the “unlicensed practice of veterinary medicine.” In Nebraska, continuing to operate a business without a license after getting a cease and desist letter is a Class III felony. So Karen could face up to 20 years in prison and pay a $25,000 fine. By comparison, that’s the same penalty for manslaughter in the Cornhusker State.

Nebraska isn’t a place that shows up in the news very often: I’ve posted nearly 5,000 entries here at the blog, and this is the first time I’ve needed to tag anything “Nebraska”.