In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes says the real Roaring Twenties were back in the eighteenth century:

Last week I called the 1720s an era of schemes. 1720 was the year of the South Sea Company’s crash, as well as the collapse of John Law’s Mississippi Company in France. But the decade saw some oft-neglected innovations too. As I never tire of saying, Britain’s extraordinary acceleration of innovation was about all industries, not just the famous ones of cotton, coal, iron, and steam — a point that the 1720s demonstrate perfectly.

For a start, it was the decade in which smallpox began to be systematically eradicated through inoculation. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, having observed the procedure in the Ottoman Empire, had her daughter inoculated in London following an outbreak in 1721. The same epidemic prompted the trialling of inoculation in New England, and the reports of these successes provided the statistical evidence for it to be more widely spread. Soon, through Lady Montagu’s aristocratic connections, even the royal children were being inoculated. Inoculation was still dangerous — it was decades before non-deadly cowpox was discovered to also confer immunity to smallpox — but the 1720s marked the beginning of the end for one of humanity’s greatest killers.

[…]

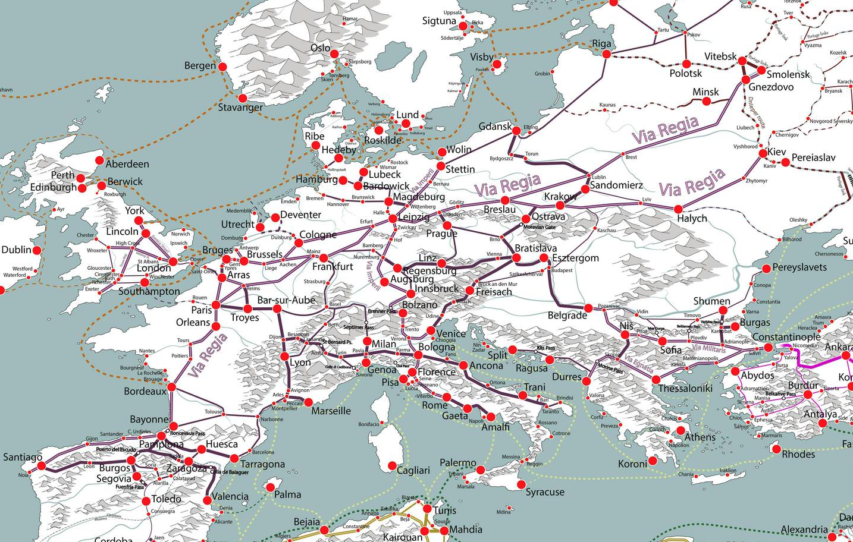

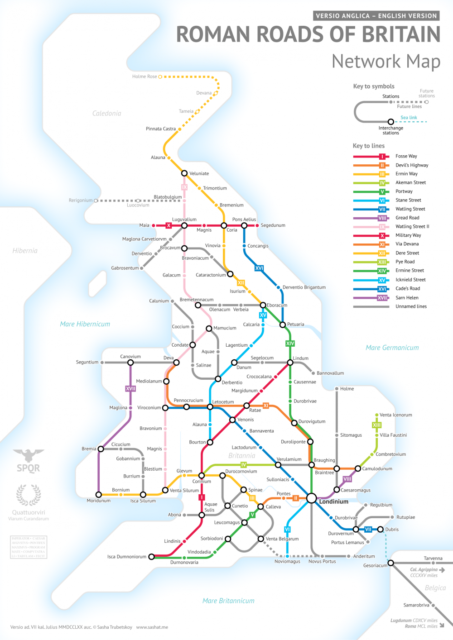

Most famous, however, was the search for longitude. When at sea, it was relatively easy to tell how far north or south you were, but not how far east or west. The implications for navigation were immense. William Whiston, a protégé of Newton, was in 1714 instrumental in lobbying for the creation of a substantial government prize for a solution, and spent much of the following decades trying to win it. His earliest proposal, along with the mathematician Humphrey Ditton, was for ships anchored at fixed locations to essentially shoot fireworks at fixed intervals. By comparing the difference between seeing and hearing the flashes, you might calculate your longitude (it’s actually not that dissimilar to the principle that underlies GPS).

Marine chronometer “Copie No. 18″, Thomas Mudge, Jr., Robert Pennington, Richard Pendleton, et al, London, 1795 – Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, Dresden.

Photo by Daderot via Wikimedia Commons.But unlike with the medical advances, the poets were having none of it. As one of them rather crudely put it:

The longitude miss’d on

By wicked Will Whiston;

And not better hit on

By good master Ditton.

So Ditton and Whiston

May both be bepist on;

And Whiston and Ditton

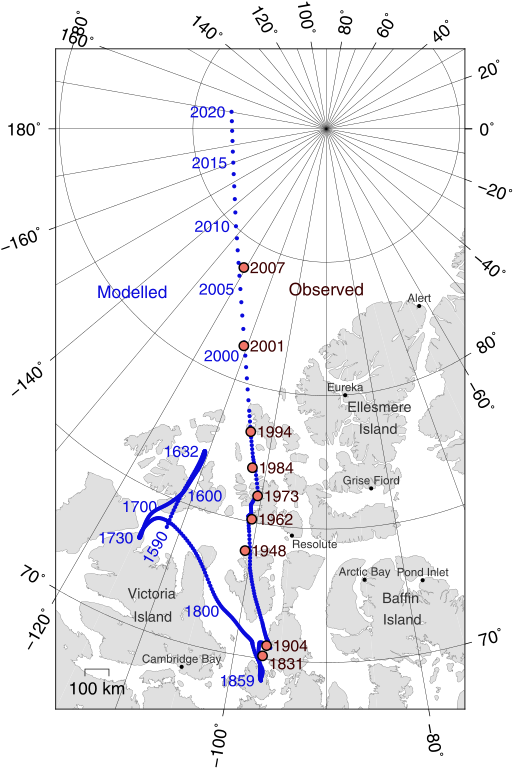

May both be beshit on.Whiston and the other longitude-searchers also investigated using the earth’s magnetic variation — he produced perhaps the first map with isogonic lines, indicating where compass needles dipped — as well as solar eclipses. And as longitude could be found on land by looking at the eclipses of Jupiter’s moons, he tried to develop telescopes so that they could observe such events on the unsteady sea.

Nonetheless, the solution came from one of George Graham’s friends, the clockmaker John Harrison. Starting in the 1720s, Harrison developed a timekeeping device — the marine chronometer — that would keep its accuracy despite the rocking and rolling and atmospheric changes from being at sea. By comparing your local time with the time at Greenwich shown on the chronometer, you could calculate your longitude. (Though by the time his device came into use in the 1770s, another method had been discovered that involved observing the moon).

And of particular interest to woodworkers who also have historical interests:

While scientific minds sought the longitude, consumer items were also being transformed. In the 1720s, a ship’s carpenter to Jamaica, Robert Gillow, was among the first to import mahogany to Britain, creating a tradition of furniture-making in Lancaster that even the fashion-conscious French would come to regard jealously.