… let’s just look at the presidents of my lifetime: JFK: Adulterer, drug user, made his brother (!) Attorney General, shady mafia connections, stole election. LBJ: Adulterer, much cruder than Trump, started Vietnam War. Nixon: Honestly, better than LBJ but the source of the term “Nixonian.” Ford: Nice guy, failed president. Carter: Nice guy, failed president. Reagan: The GOP gold standard, but a multiply-divorced Hollywood actor whose administration was marked by nearly as much scandal-drama as Trump’s. (Just look up Justice Gorsuch’s mother). George HW: Nice guy, but longtime adulterer and failed president. Bill Clinton: I mean, come on. George W. Bush: Personal rectitude in office, though he’s been a bit of a dick since Trump beat his brother. Iraq War thing didn’t turn out too well. Mediocre judicial appointments and little attention to domestic reforms. Gave us TSA. Obama: Far more scandals, and far more abuse of power, than Trump. And does French forget that Trump was running against Hillary?

Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds, “I LIKE DAVID FRENCH, BUT THIS IS AHISTORICAL BULLSHIT”, Instapundit, 2019-04-20.

May 21, 2019

September 14, 2017

Ken Burns and Lynn Novick: The Vietnam War Is the Key to Understanding America

Published on 13 Sep 2017

Nick Gillespie interviews Ken Burns and Lynn Novick about their new documentary series: The Vietnam War.

The Vietnam War led to more than 1.3 million deaths and it’s one of the most divisive, painful, and poorly understood episodes in American history.

Documentarians Ken Burns and Lynn Novick have spent the past decade making a film that aims to exhume the war’s buried history. Their 10-part series, which premieres on PBS next week, is a comprehensive look at the secrecy, disinformation, and spin surrounding Vietnam, and its lasting impact on two nations. The 18-hour film combines never-before-seen historical footage, with testimonies from nearly 80 witnesses, including soldiers on both sides of the conflict, leaders of the protest movement, and civilians from North and South Vietnam.

A two-time Academy Award winner, Burns is among the most celebrated documentary filmmakers of our time, best-known for the 1990 PBS miniseries The Civil War, which drew a television viewership of 40 million. He and Novick are longtime collaborators, and in 2011 she co-directed and produced Prohibition with Burns. In 2011, Reason’s Nick Gillespie interviewed Burns that film and the role of public television in underwriting his work.

With the release of The Vietnam War, Gillespie sat down with Burns and Novick to talk about the decade-long process of making their new film, and why understanding what happened in Vietnam is essential to interpreting American life today.

Produced by Todd Krainin. Cameras by Meredith Bragg, Mark McDaniel, and Krainin.

Full interview transcript available at http://bit.ly/2x0e5U4

June 15, 2017

Words & Numbers: What You Should Know About Poverty in America

Published on 14 Jun 2017

Poverty is a big deal – it affects about 41 million people in the United States every year – yet the federal government spends a huge amount of money to end poverty. So much of the government’s welfare spending gets eaten up by bureaucracy, conflicting programs, and politicians presuming they know how people should spend their own money. Obviously, this isn’t working.

This week on Words and Numbers, Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan delve into how people can really become less poor and what that means for society and the government.

April 19, 2017

QotD: Hubris and Nemesis, or pride goeth before the fall

Few things are more likely to precede defeat than the conviction that you are on the verge of victory. One hundred years ago, in the spring of 1917, Germany had every reason to believe that it would triumph over its enemies in the First World War. France had been bled white in repeated attacks on the German army’s fortified lines, England was suffering from shortages of both munitions and military manpower, and Russia was descending into a revolution that would, within a year, enable Germany and its Austro-Hungarian allies to shift enormous numbers of troops and guns to the Western Front. Yet the entry of the United States into the war on April 6, 1917, proved to be the counterweight that shifted the balance. By the autumn of 1918, the fond hope of Germany victory had been exposed as a delusion. The ultimate result of the Kaiser’s war was the destruction of the Kaiser’s empire, and of much else besides.

What is true in war is true also in politics. Hubris is nearly always the precedent to unexpected defeat. In 1964, Lyndon Johnson won a landslide victory; less than four years later, LBJ could not even win his own party’s nomination for re-election. In 1972, Richard Nixon was re-elected in a landslide; less than two years later, he was forced to resign from office. More recently, after George W. Bush’s 2004 re-election, some imagined that this victory was the harbinger of a “permanent Republican majority” — a GOP electoral hegemony based on a so-called “center-right” realignment — but two years later, Democrats captured control of Congress and in 2008 Barack Obama was elected president. Obama’s success in turn led Democrats to become overconfident, and Hillary Clinton’s supporters believed they were “on the right side of history,” as rock singer Bruce Springsteen told a rally in Philadelphia on the eve of the 2016 election. Unfortunately for Democrats, history disagreed.

Robert Stacy McCain, “Why Is the ‘Right Side of History’ Losing?”, The American Spectator, 2017-04-05.

January 5, 2017

Thomas Sowell

David Warren on the recently announced retirement of economist Thomas Sowell:

Born in the rural poverty of North Carolina, raised in Harlem, he remained personally acquainted with the fate of his race. A disciplined and unexciteable controversialist, he rose closest to exhibiting passion when discussing, for instance, the destruction of the black family by the Great Society of Lyndon Baines Johnson — how it arrested the social and economic advancement blacks had been making by their own efforts to overcome the monstrous history of slavery. By its “helping hand” the government rewarded unwed motherhood, punished enterprise, and promoted crime. In addition to family, it undermined religion, and finally helped install the abortion mills which disproportionally reduce the black population. And all of this by legislation drumrolled from the start with pseudo-Christian moral posturing.

Sowell could understand this through the economic analysis of moral hazard. Reward people for making irresponsible life choices, for discarding prudence and embracing victimhood and dependency — the result may be predicted. The question whether the policies were the product of invincible stupidity or demonic inspiration is moot: for stupidity is among the devil’s excavating tools. He is a master policy analyst, to whom men are merely statistics to be crunched; and to the stupid man he proposes the job-ready shovel, by which to dig his own grave.

January 17, 2016

QotD: The entrenchment of American political tribes

We learned that much of the increase in political polarization was unavoidable. It was the natural result of the political realignment that took place after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The conservative southern states, which had been solidly Democratic since the Civil War (since Lincoln was a Republican) then began to leave the Democratic Party, and by the 1990s the South was solidly Republican. Before this realignment there had been liberals and conservatives in both parties, which made it easy to form bipartisan teams who could work together.

[…]

But we also learned about factors that might possibly be reversed. The most poignant moment of the conference came when Jim Leach, a former Republican congressman from Iowa, described the changes that began in 1995. Newt Gingrich, the new speaker of the House of Representatives, encouraged the large group of incoming Republicans to leave their families in their home districts rather than moving their spouse and children to Washington. Before 1995, Congressmen from both parties attended many of the same social events on weekends; their spouses became friends; their children played on the same sports teams. But nowadays most Congressmen fly to Washington on Monday night, huddle with their teammates and do battle for three days, and then fly home on Thursday night. Cross-party friendships are disappearing; Manichaeism and scorched Earth politics are increasing.

Jonathan Haidt, quoted by Scott Alexander in “List Of The Passages I Highlighted In My Copy Of Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind“, Slate Star Codex, 2014-06-12.

July 10, 2015

July 3, 2014

How the Great Society failed American blacks

Fred Siegel reviews Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make it Harder for Blacks to Succeed, by Jason Riley:

A half-century ago, the Great Society promised to complete the civil rights revolution by pulling African-Americans into the middle class. Today, a substantial black middle class exists, but its primary function has been, ironically, to provide custodial care to a black underclass — one ever more deeply mired in the pathologies of subsidized poverty. In Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make it Harder for Blacks to Succeed, Jason Riley, an editorial writer for the Wall Street Journal who grew up in Buffalo, New York, explains how poverty programs have succeeded politically by failing socially. “Today,” writes Riley, “more than 70 percent of black children are born to unwed mothers. Only 16 percent of black households are married couples with children, the lowest of any racial group in the United States.” Riley attributes the breakdown of the black family to the perverse effects of government social programs, which have created what journalist William Tucker calls “state polygamy.” As depicted in an idyllic 2012 Obama campaign cartoon, “The Life of Julia,” a lifelong relationship with the state offers the sustenance usually provided by two parents in most middle-class families.

Riley’s own life experience gives him powerful perspective from which to address these issues. His parents divorced but both remained attentive to him and his two sisters. His sisters, however, were drawn into the sex-and-drug pleasures of inner-city “culture.” By the time he graduated from high school, his older sister was a single mother. By the time he graduated from college, his younger sister had died from a drug overdose. Riley’s nine-year-old niece teased him for “acting white.” “Why you talk white, Uncle Jason?” she wanted to know. She couldn’t understand why he was “trying to sound so smart.” His black public school teacher similarly mocked his standard English in front of the class. “The reality was,” Riley explains, “that if you were a bookish black kid who placed shared sensibilities above skin color, you probably had a lot of white friends.”

The compulsory “benevolence” of the welfare state, borne of the supposed expertise of sociologists and social planners, undermined the opportunities opened up by the end of segregation. The great hopes placed in education as a path to the middle class were waylaid by the virulence of a ghetto culture nurtured by family breakdown. Adjusted for inflation, federal per-pupil school spending grew 375 percent from 1970 to 2005, but the achievement gap between white and black students remained unchanged.

August 5, 2012

A quixotic quest to rehabilitate the reputation of Richard Nixon

President Richard Nixon’s reputation could hardly be any worse: he’s seen as the most evil president if not of all time, certainly of the 20th century. Conrad Black attempts to correct the record:

Forty years after Watergate, as the agreed demonology of that drama begins to unravel and the chief authors of it, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, struggle to keep the conventional wisdom about it intact as an article of righteous liberal faith, a factual review is timely. When Richard Nixon was inaugurated president in 1969, the United States had 550,000 draftees in Indochina with no plausible explanation or constitutionally legitimate reason for them to be there and 200 to 400 of them were coming back every week in body bags. President Lyndon Johnson had offered Ho Chi Minh deferred victory in his Manila proposal of October 1966: withdrawal of all foreign forces from South Vietnam. Ho could have taken the offer and returned six months after the Americans had left, saved his countrymen at least 500,000 combat dead, and lived to see a communist Saigon. He chose to not even give LBJ a decent interval for defeat and insisted on militarily humiliating the United States.

In January 1969, there were no U.S. relations with China, no arms control talks in progress with the U.S.S.R., no peace process in the Middle East, there were race or anti-war riots almost every week all over the United States, and the country had been shaken by the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy (both in their early 40s). LBJ could not go anywhere in the country without demonstrations, as students occupied universities and the whole country was in tumult.

Four years later, Nixon had withdrawn from Vietnam, preserving a non-communist South Vietnam, which had defeated the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong in April 1972 with no American ground support, though heavy air support. He had negotiated and signed the greatest arms control agreement in world history with the Soviet Union, founded the Environmental Protection Agency, ended school segregation and avoided the court-ordered, Democratic Party-approved nightmare of busing children all around metropolitan areas for racial balance, and there were no riots, demonstrations, assassinations or university occupations. He started the Middle East peace process, reduced the crime rate and ended conscription. For all of these reasons, he was re-elected by the greatest plurality in American history, 18 million votes, and a percentage of the vote (60.7) equalled only by Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936. His term was rivalled only by Lincoln’s and FDR’s first and third terms as the most successful in U.S. history.

June 19, 2012

Robert Fulford: 1963-74 was a period where “everything connects in a web of deceit, paranoia and distorted ambition”

An interesting article by Robert Fulford in the National Post, discussing the time between the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the resignation of Richard Nixon. I was too young to pay any attention to politics in those days, and I only started being aware of how weird it was through reading Hunter S. Thompson’s political writings of the time — and I still think it’s a great encapsulation of the bottled insanity of the US political system of that era.

For 11 years, 1963 to 1974, tragedy and shame were the most persistent themes of American politics. That period has never been given a name, but after four decades it feels like a distinct unit in history. From the death of John Kennedy to the resignation of Richard Nixon, everything connects in a web of deceit, paranoia and distorted ambition.

[. . .]

Even after ultimate power fell into Johnson’s hands, it left him squirming in frustration and rage. He was triumphant for a brief moment, pushing through Congress laws that opened society to black Americans. But he felt surrounded by enemies. Although he asked Kennedy’s men to stay on, he never trusted them. When Malvolio leaves the stage he threatens, “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you.” That was how Johnson felt about Bobby Kennedy. Caro is especially good on the bitter 15-year struggle that consumed these two men, both smart but both hopelessly lacking in self-awareness.

Johnson’s second downfall, the swiftly increasing Vietnam war, was also America’s tragedy, a fruitless enterprise that cost many lives and wrecked American confidence in Washington. As Caro now says, “Everyone thinks distrust of government started under Nixon. That’s not true. It started under Johnson.” On Vietnam he lied so consistently that Americans ceased to believe anything he said. Journalists spoke euphemistically of his “credibility gap.” Trust in the political class never returned.

With Johnson so dishonoured that he couldn’t run for re-election in 1968, Nixon succeeded him. He brought with him a style darker and more paranoid even than Johnson’s. In covering up a break-in by his party’s operatives at the Watergate complex, he revealed that everything said about him by his worst enemies was true.

[. . .]

From beginning to end, Schlesinger despised Nixon. In 1962, when Nixon brought out his self-revealing memoir, Six Crises, demonstrating that his main interest in life was judging how others saw him, Schlesinger wrote in his diary “I do not see how his political career can survive this book.” Schlesinger, while he served power-mad leaders, didn’t understand them. He couldn’t imagine that just six years later, in 1968, Nixon’s furious ambition would make him president and then get him re-elected to a second term, the one he failed to complete because Watergate made him the first American president ever to resign in disgrace, a fate even worse than Johnson’s.

Schlesinger’s book provides an accompaniment to this heartbreaking era of shame. It never fails to remind us that, no matter what theories the historians construct, the course of history is usually shaped by a few frail, frightened and often deeply damaged human beings.

April 17, 2012

The US Navy’s next destroyer will be the USS Lyndon B. Johnson

I guess they’re happy they don’t have to use that particular name on an aircraft carrier:

Strike one against the U.S.S. Lyndon Johnson: the Gulf of Tonkin incident. A confusing episode off the Vietnamese coast on August 2, 1964 resulted in a brief maritime skirmish with the North Vietnamese. The destroyer U.S.S. Maddox got shot; one of its aircraft was damaged. It was unclear who fired first. (A claimed follow-on engagement two days later was ultimately determined to have been a fiction.) Johnson’s administration, seeking an excuse to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam, portrayed the incident to Congress as a clear-cut act of North Vietnamese aggression. A decade later, the futile Vietnam war had claimed 57,000 American lives.

Strike two: Lyndon Johnson’s Naval war record was similarly dubious. As Johnson’s magisterial biographer, Robert Caro, documented in Means of Ascent, Johnson’s Naval commission in World War II was the result of string-pulling. (Johnson was a sitting congressman at the time; he sought a commission to bolster his political career.) His military career consisted of a single combat flight over the Pacific for which he received a Silver Star. For the next two decades, Johnson repeatedly exaggerated his tall tale of defying a Japanese Zero.

Strike three: the U.S.S. Lyndon Johnson will be a Zumwalt-class destroyer — a class of ship singled out by good-government watchdogs as an unaffordable boondoggle.

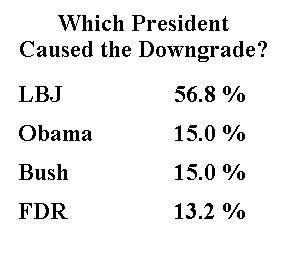

Well, it turns out that Social Security is a relatively minor part of the problem, so even though President Roosevelt’s policies exacerbated and extended the Great Depression, the program he created is only responsible for a small share of the fiscal crisis. To give the illusion of scientific exactitude, let’s assign FDR 13.2 percent of the blame.

Well, it turns out that Social Security is a relatively minor part of the problem, so even though President Roosevelt’s policies exacerbated and extended the Great Depression, the program he created is only responsible for a small share of the fiscal crisis. To give the illusion of scientific exactitude, let’s assign FDR 13.2 percent of the blame.