Probably the most common definition is “the science of allocating scarce resources to diverse ends.” [Michael] Watts offers Marshall’s definition: The study of mankind in the ordinary business of life. Neither of those is what I think of as economics. Still less is it the study of the economy, which I suspect would come closest to what most people think the word means.

To me, economics is that approach to understanding behavior that starts from the assumption that individuals have objectives and tend to take the acts that best achieve them. That is what economists mean by “rationality,” and it is the assumption of rationality that is, in my view, the distinguishing characteristic of economics. What I am looking for are works that tell us something interesting about the implications of that assumption.

Someone at some point suggested Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. It is an interesting book, although much too long for my purposes. But what makes it interesting, economically speaking, is not the vivid picture of poverty in the period between the wars but particular details relevant to implications of rational behavior.

I can give, by memory, an example. Orwell observed waiters in a fancy Paris restaurant, out of sight of the diners, spitting in the dishes they were going to serve. In an idealized market context, the waiter would never spit in the dish unless the value to him of doing so was more than the disvalue to the patron he was serving, which is unlikely. But throw in the inability of either the patrons or the waiter’s employers to monitor the waiter’s behavior and any benefit to the waiter of expressing his hostility is a sufficient incentive to make him do it. That suggests the further point that, when you cannot monitor someone’s behavior, his preferences matter — you want the job he is doing for you to be done by someone whose preferences are close enough to yours so that he will want to do what you would want him to do — even if nobody is watching.

Economics is not the study of the economy. A picture of poverty, or unemployment, or wealth, or economic growth, however accurate and vivid, does not in itself teach you any economics. A story such as Poul Anderson’s “Margin of Profit,” which deals with a wholly fictional future, does, because it demonstrates in that world an important implication of rationality that holds in our world as well — that in order to prevent someone from doing something you do not want him to do it is not necessary to make it impossible, merely unprofitable.

David Friedman, “Thoughts on Literature, Economics and Education”, Ideas, 2017-05-01.

June 9, 2019

QotD: What is economics?

December 1, 2018

CAFE killed the North American passenger car

The move by GM to close many of its remaining car manufacturing facilities in Canada and the US is a belated rational response — not to the market, but to the ways government action has distorted the market. In the Financial Post, Lawrence Solomon explains how, step-by-step, the CAFE rules have shifted drivers out of sedans and wagons and into minivans, pickup trucks, and SUVs:

Before the U.S. government introduced Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards to increase the distance cars could travel per gallon of gas, sedans and full-size station wagons were popular and SUVs were unknown. CAFE, which effectively governed the entire North American market thanks to the Canada-U.S. Auto Pact, incented manufacturers to artificially raise the cost of large passenger cars in order to favour smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles. It soon claimed its first victim: the full-size station wagon, whose flexible interior accommodated both passenger and cargo needs, and which, at its peak, came in 62 models to satisfy different tastes.

But, although CAFE priced the station wagon out of the market, the market still demanded a vehicle that offered its flexibility. Enter Lee Iacocca, the chairman of Chrysler, who helped develop the minivan and convinced the U.S. government to deem it a truck rather than a passenger vehicle, thus exempting it from the strict CAFE standards that killed the station wagon. The minivan took off — the first 1984 model, built in Windsor, sold 209,000 its first year — followed by the SUV, which also was deemed a truck rather than a passenger vehicle. By 2000, the passenger car had less than half the market. Today it accounts for only about a third.

CAFE standards didn’t only claim certain car models as victims, they also made the whole industry a victim by making it dependent on government whims and then handouts. CAFE also distorted the market by creating credits for ethanol and electric vehicles and by creating a lobbyist’s dream through ever-changing regulations that led car manufacturers to continually game the system to favour their own vehicles over those of competitors.

Perversely, by improving mileage, CAFE also increased distances travelled and emissions of pollutants such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides. The 2025 CAFE targets (since cancelled by President Trump) ran to almost 2,000 pages and were estimated to add an average of US$1,946 to the cost of a vehicle. Tax loopholes also helped accelerate SUV sales — like all light trucks, they were exempted from the gas-guzzler’s excise tax and also given preferential tax treatment as business vehicles.

October 26, 2018

Economist Jack Mintz dis-claims credit for the Liberals’ carbon tax scheme

Everybody likes to be recognized for their work, but Jack Mintz wants to delineate where his original plan and the actual carbon tax scheme implemented by the federal government diverge:

I continue to maintain, as I have all these years, that the best way to implement carbon taxes is to use the revenues to reduce harmful corporate and personal taxes (I’ve since added land-transfer taxes to the original list). This includes removing anti-competitive levies while also providing support for low-income households to cope with higher electricity, heating and transportation costs.

However, what was unveiled Tuesday by the federal Liberal government in its carbon-pricing plan fails to achieve what I would have argued to be an ideal carbon policy. What is being advertised as a climate plan for provinces that fail to follow Ottawa’s carbon-tax directives — currently New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, but they’ll likely be joined by others — instead comes across as a grand redistribution scheme administered by an expanding government bureaucracy.

While the federal carbon tax is almost uniform (electricity is not yet included), it provides special exemptions for certain sectors such as farmers, fishers, aviation, power producers in the North and greenhouse operators, although not the ones growing recreational cannabis.

But the departure from uniformity is marginal and not nearly as concerning as the Trudeau government’s continuing commitment to existing and even new regulations and subsidies to promote “clean energy,” each with their implicit carbon price. While economists repeatedly argue for a carbon tax precisely because it means we can forgo these high-cost interventions, somehow that has all been lost. While plenty of the economists behind the carbon-tax lobby were cheering Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s new plan yesterday, I somehow missed their demands that we now must eliminate clean fuel and renewable electricity standards, subsidies for electric vehicles and ethanol — all of which have carbon costs well in excess of the $50-a-tonne carbon tax planned for 2022.

Another failure of the federal plan is to pass on carbon taxes in the form of Justin Bucks — or, to use the more laborious official name for these tax rebates: Climate Action Incentive Payments. So, rather than include carbon taxation as part of a comprehensive tax reform to make the tax system simpler, less distorting and fair, these Justin Bucks will be paid to households, small businesses, municipalities, universities, colleges, hospitals, non-profit and Indigenous populations.

A fatal flaw in federal pricing plan is a major shift in taxes from individuals to businesses. The average per household rebate — $1,161 in Saskatchewan in 2022 for example — is more than the cost per household of $946 (not including GST or HST on any energy bills). Even though the document states that business taxes are fully shifted forward to households, something is amiss here. How can household rebates average more than costs?

October 25, 2018

It’s not a “bribe” … it’s an “incentive”!

Terence Corcoran explains why the federal government’s promised “incentive” isn’t in any way, shape, or form any kind of bribe:

Step right up, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome aboard the all-new Canadian Cynical Circular Carbon Circus, the amazing Liberal climate control spectacle that will send you on a great environmental ride into the future.

Come on in! We will pay you to not consume fossil fuels — as individuals and as industries. It’s an economic revolution that takes us beyond blockchain and cryptocurrencies and cannabis into a brave new universe in which money goes round and round and everybody wins. We will pay Canadians with their own money — more than $20 billion over five years in carbon taxes that will raise the price of gasoline by 11 cents a litre by 2022, and ever higher thereafter if not sooner. Everybody pays and everybody wins, except for those who don’t. And some people win more than they pay. It’s better than a lottery!

For the people of Ontario, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and New Brunswick, the federal carbon circus cash comes via a new “Climate Action Incentive Payment.” An Ontario family of four will receive $307 for this year, the amount to be claimed on 2018 income tax returns. A Saskatchewan family will get a Climate Action Incentive Payment of $609.

What’s the Climate Action Incentive Payment for? The Liberal plan unveiled by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Environment Minister Catherine McKenna Tuesday doesn’t specify. What are taxpayers in the four provinces being incented to do, exactly, with this new wad of free cash? There is only one explanation: Vote Liberal in 2019!

The payments are based on a 2019 carbon price of $20 a tonne, rising to $50 by 2022. As the carbon tax goes up, Ontario families will receive $718 in 2022 and Saskatchewan families $1,459. And there will be more to come, presumably, since the latest doomsday scenario from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — the font of all speculation and data manipulation on climate issues — warned that by 2030 (only 12 years from now) a carbon price of somewhere between $135 to $5,500 per tonne would be needed to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

October 12, 2018

Carbon taxes may be efficient, but let’s not rush into it quite yet…

Terence Corcoran says we shouldn’t jump at the chance to kill our economy just because carbon taxes are efficient:

It didn’t take long for federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna to tweet out the news implying that the Nobel committee supported the government of Canada’s carbon-price scheme. The Montreal-based carbon-taxing NGO, the Ecofiscal Commission, hailed Nordhaus for having “demonstrated” that a universal price on carbon was the most “efficient” way to curb climate change.

Before jumping aboard the Nordhaus bandwagon, however, carbon-taxing politicians and all Canadians might want to take a closer look at what they are being led into.

[…]

Nordhaus and his co-winner of this year’s Nobel in economics, former Stanford economist Paul Romer, are great believers in “incentives.” As Romer said in a post-Nobel interview (tweeted by McKenna, naturally): “I believe, and I think Bill (Nordhaus) believes, that if we start encouraging people to find ways to produce lower carbon energy, everybody’s going to be surprised at the progress we’ll make as we go down that path. All we need to do is create some incentives that get people going in that direction, and that we don’t know exactly what solution will come out of it — but we’ll make big progress.”

But why a tax? If all we need to do is deploy the price mechanism, why impose a tax? Let’s ignore for a moment the dubious assumption that the science and economics of climate change are sound and settled. Would it still not be better to have the government set the carbon price, require the energy companies to charge it, but allow the revenue to flow not to government but through to energy companies and their shareholders, and others in the supply chain? That’s where market forces and the above-mentioned miracle price mechanisms — rather than government planners — would determine where to invest and what energy alternatives are best. (No gas retailer could possibly eat the cost of a 90-cent-per-litre carbon tax, so they’d have no choice but to pass at least most of it along to the customer).

One of the ironies of carbon taxation is the enthusiasm for “market mechanisms” and “prices” among politicians who otherwise abhor and resist market pricing of everything from roads to health care to rental housing to public transit to education to broadcasting and telecom and the internet and the price of cannabis, not to mention the Canadian price of milk and chickens. With carbon, market pricing is suddenly a great idea, no matter how fanciful the analyses and speculative the projections.

September 26, 2018

Reforming Union Pacific

Fred Frailey explains why the vast Union Pacific system is due for some serious economic streamlining:

Union Pacific locomotive 5587, a General Electric AC4400CW-CTE (AC44CWCTE)

Photo by Terry Cantrell via Wikimedia Commons.

Union Pacific is the ideal lab rat for Precision Scheduled Railroading, practiced by the late Hunter Harrison on four Class I railroads, with great rewards for shareholders and mixed results for customers. UP, which will begin recasting itself October 1, is ideal for the role because it has too many employees, too many unproductive route miles, and too many expensive toys. Plus, it is less interested in increasing market share than in maximizing freight rates, which makes right-sizing the railroad easier. Let’s start by running the numbers.

Employees. At the peak of the last railroad cycle in 2006, Union Pacific had already been lapped by its western competitor, BNSF Railway, in both cars originated and revenue ton miles. Since then, through 2017, UP’s originations and revenue ton miles both fell 17 percent, while BNSF RTMs actually set a record in 2017. Yet at 44,146 employees last year, UP’s employee count was still 7 percent higher than that of BNSF. To put this another way, for UP’s productivity per employee (revenue ton miles per worker) to equal its competitor’s, it would need to slice the headcount by 16,000. A place to start might be headquarters in Omaha. UP counted 3,678 executives, officials and staff assistants in 2017 versus BNSF’s 1,511.

Barren route miles. Salina, Kan., to Provo, Utah, is becoming a traffic wasteland. That didn’t stop UP from laying welded rail and concrete ties and from covering the almost 1,000 miles with centralized traffic control. Meanwhile, one train a day (plus Amtrak) operates In Missouri between St. Louis and Poplar Bluff, Ark. And the railroad has effectively ceased freight service between Watsonville Junction and San Luis Obispo, Calif., and is close to doing so over the rest of the Coast Line to Los Angeles. All of these routes and perhaps many others you can identify contribute little revenue but buckets of costs, inflating the operating ratio (which is the percentage of revenues eaten up by operating costs). They would constitute Hunter Harrison’s first target.

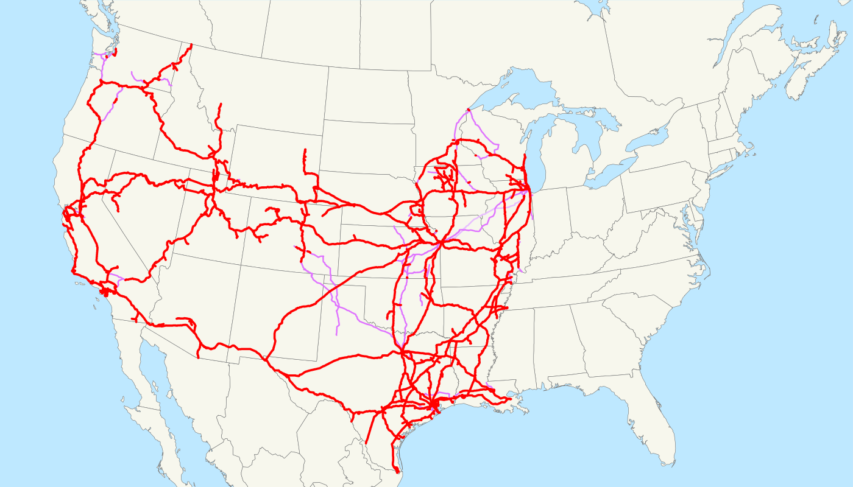

Map of the Union Pacific Railroad as of 2008, with trackage rights in purple (the special Chicago-Kansas City intermodal trackage rights are lighter).

Image via Wikimedia Commons.[…]

Moreover, there are aspects to PSR as practiced by Hunter Harrison that customers won’t like. At the core of Precision Scheduled Railroading is intense use of assets: Run as many trains every day one direction as you do the other, fill them to maximum designed length and operate them at similar speeds. This isn’t how the commercial world works, and the Hunter Harrison way to make customers ship seven days a week was to discount rates on slow days and slap on surcharges on busy days. This keeps your crews and equipment fleet in motion at all times, and those cars and locomotives not continually used can be retired. Goodbye to growth and increased market share, which is a messy process requiring you to accede to the needs of customers rather than the other way around. But it is efficient.

However, if Union Pacific is serious about serving its customers better and delivering individual cars rather than trains to their destinations on schedule, I have an idea that I guarantee will achieve that result: Base salaried bonuses and stock grants on UP’s success in getting cars to customers on the right day and time and on the right train. UP has scheduled individual cars for decades, but there have never been monetary consequences for achieving those plans. People do follow the money. And when Union Pacific does for customers what it says it will do, calling the process Precision Scheduled Railroading or whatever you wish, I will be leading the applause.

September 25, 2018

QotD: The Laffer Curve

Around a certain sort of leftist mention of the Laffer Curve just brings a derisive snort. The sadness of that reaction being that it’s just an obvious mathematical truth. Tax rates of 0 % and 100 % bring in no revenue. Somewhere in between maximises the moolah. Note what isn’t being said, that all tax cuts always pay for themselves, nor even that lower tax rates are necessarily a good thing. Only that there’s some optimal level with regard to revenue collection.

All the arguments about the optimal level of government are over in the Wagner Curve and such others.

The Laffer Curve is also made up of two components, the income and substitution. Some people will work just to make their nut. Observational studies have shown that many taxi drivers do. So, increase their tax rates and they’ll work more. The substitution effect is, well, what’s that net wage worth to me? What’s the value of not working? When going fishing is worth more than working then people will go fishing. The curve as a whole is the interplay of these two effects.

Each tax in each society has its own such curve. A transactions tax of 0.01% can reduce revenue collection, as the EU’s study of a financial transactions tax shows us. Taxes upon income of 20% are below that Laffer Curve peak.

But where, exactly, is that peak for taxes upon income? The best study we’ve got, Saez and Diamond, says between 54% and 80% dependent upon other structures in the tax system. The Tory part of the UK Treasury says around 40 to 45% for income tax, plus national insurance, so at the bottom end of that S&D range. Many lefties want to say it’s higher so we can tax “the rich” more.

Tim Worstall, “How Lovely To Spot The Laffer Curve In The Wild – Doctors’ Pensions Edition”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-09-05.

July 17, 2018

QotD: The incentive problem for universities

Incentives matter. This is a fundamental tenet of economics: People respond to their incentives. If something in a market seems to be going wrong, it’s because the incentives have gotten screwed up.

Looking at the market for education, it’s hard not to think that there’s something wrong with the incentives. Tuition keeps going up and so does debt. The percentage of people who are not paying off that debt — either because they are in default, deferment, or an income-based repayment program — is staggering. Naturally, a lot of folks would like to get the government in there to start tweaking those incentives until the market stops being so crazy.

One issue involves the incentives that schools have to ensure that their graduates get value out of their degrees. At the moment, a school can enroll you in practically any program, and the government will lend you money for tuition and living expenses, whether or not that degree is likely to produce the means to repay the loan. Since schools are often in a better position to know the economic value of their degrees than naive potential students, that twists the incentives. Eventually, the student will pay, either with money or trashed credit. If the loan defaults, taxpayers will pay too. The school has the most information about the transaction and yet it has the least at stake. No wonder we have such high tuition, so many dubious degree programs and such a troubling rate of default.

Megan McArdle, “Don’t Make Colleges Pay for Student-Loan Defaults”, Bloomberg View, 2016-09-07.

July 2, 2018

QotD: Perverse incentives, death penalty edition

People cheered when, in the 1990s, Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich advocated mandatory executions for drug dealers. But economists wondered why Gingrich wanted to decrease the penalty for murder. How does the death penalty for drug dealers decrease the penalty for murder? Think about it this way: Suppose that Gingrich’s bill becomes law and the police bust into an apartment where three drug dealers have hidden their stash. What happens? The drug dealers know that if they give up, they will be put to death. So why not try to kill the police? If the dealers are lucky, they get away. If the dealers are unlucky, they are no worse off than if they didn’t fight because when drug dealing is a capital offense, drug dealers face no additional penalty for murder.

Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok, Modern Principles: Microeconomics (3rd Edition), 2015.

May 28, 2018

QotD: Correcting mistakes in private and public enterprises

… government cannot do just one thing, and some of the repercussions of what it chooses to do will be, as it were, mistakes in the perspective of the public even if the initial action were not. But the public’s dissatisfaction with these adverse outcomes can make itself known only via the politically charged process of complaint to authorities, petition for redress of grievance, lobbying, payoffs to public officials, and all the rest of the endlessly complex apparatus for the operation of the government’s political and bureaucratic setup. One is lucky to get any constructive response at all from the government, whose effective control is apt to be in the hands of entrenched politicians, bureaucrats, and private-sector cronies in the various iron triangles that pervade the state at large. If one does succeed in getting a constructive response, it is likely to come forth only after years of expensive and time-consuming delays.

This lack of an effective feedback-incentive mechanism is among the greatest flaws of all government activities. Markets, in contrast, are certainly not perfect relative to the model criteria economists have devised to evaluate them, but they are undoubtedly superior in the operation of their feedback information and response to mistakes. To remove an activity from the market and place in under government control is to ensure that henceforth mistakes, whether they arise from bad judgement, corruption, or ignorance, will not elicit a proper or timely response. In the government realm, mistakes and the slow, counter-productive responses, like doomed lovers, sink together slowly in the quicksand of bad actions being made ever worse by ill-fated reactions.

Robert Higgs, “Dealing with Mistakes: Government Action versus Private Action”, The Beacon, 2016-08-17.

May 21, 2018

QotD: The key difference between private and public enterprise is effective feedback

State bureaucracies are notoriously inept in reacting constructively to their own mistakes. For example, they continuously seek to increase their budgets, staffs, and authority, even when their projects have proven counter-productive or disastrous. It’s almost as if they promote their institutional objectives best by fouling up their programs, then coming back to their funding sources to explain that they cannot succeed unless they receive more resources to do so. Thus do public agencies pour money and effort down the rat hole for years on end, wasting the public’s money every step of the way. The feedback system in this case is obviously perverse so far as serving the public interest is concerned.

Such perversity is practically guaranteed in government operations because government operates outside the realm of private property rights, the price system, and the profit-and-loss accounting that constitute a feedback system in the market realm. In the market, money-losing projects do not persist indefinitely. Their owners and managers eventually decide against throwing good money after bad and close the unprofitable operations. Owners who refuse to read and respond correctly to the clear message transmitted by profits and losses suffer reductions of their own wealth, which serves as a powerful incentive to act correctly and to rectify the mistakes they have made before even more wealth goes down the drain.

Robert Higgs, “Dealing with Mistakes: Government Action versus Private Action”, The Beacon, 2016-08-17.

April 25, 2018

March 19, 2018

QotD: Unintended consequences, recycling division

The hallmark of science is a commitment to follow arguments to their logical conclusions; the hallmark of certain kinds of religion is a slick appeal to logic followed by a hasty retreat if it points in an unexpected direction. Environmentalists can quote reams [!] of statistics on the importance of trees and then jump to the conclusion that recycling paper is a good idea. But the opposite conclusion makes equal sense. I am sure that if we found a way to recycle beef, the population of cattle would go down, not up. If you want ranchers to keep a lot of cattle, you should eat a lot of beef. Recycling paper eliminates the incentive for paper companies to plant more trees and can cause forests to shrink.

Steven Landsburg, The Armchair Economist, 1993.

February 14, 2018

Repost: “I, Rose” and “A Price is Signal Wrapped Up in an Incentive”

Published on 8 Feb 2015

How is it that people in snowy, chilly cities have access to beautiful, fresh roses every February on Valentine’s Day? The answer lies in how the invisible hand helps coordinate economic activity, Using the example of the rose market, this video explains how dispersed knowledge and self-interested actors lead to a global market for affordable roses.

Published on 8 Feb 2015

Join Professor Tabarrok in exploring the mystery and marvel of prices. We take a look at how oil prices signal the scarcity of oil and the value of its alternative uses. Following up on our previous video, “I, Rose,” we show how the price system allows for people with dispersed knowledge and information about rose production to coordinate global economic activity. This global production of roses reveals how the price system is emergent, and not the product of human design.

January 31, 2018

QotD: “Enhancing the user experience”

Once upon a time, computers weren’t all constantly connected to the intertubes. What we call “air-gapped” these days was the normal state of machines back in the desktop beige box days.

Back then, when you bought a program it came in a cardboard box on physical media. You would install it on your computer and it would work the same way from the day you installed it to the day you stopped using it. Nobody could rearrange the menus on WordPerfect or change the buttons in Secret Weapons of the Lufwaffe … Good times.

Nowadays, half the software you interact with doesn’t even reside on your PC. Further, there are whole departments at, say, Facebook or Blizzard or Google whose entire job is to “enhance the user experience”. If they’re not constantly dicking around, adding and removing features, changing what buttons do, moving things around … then they’re not doing their jobs.

We have incentivized instability.

Tamara Keel, “Tinkering for tinkering’s sake…”, View From The Porch, 2018-01-10.