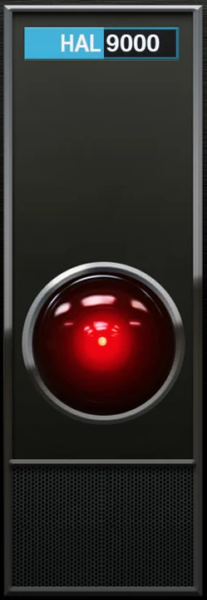

Ted Gioia explains the deep history behind the scene in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey where H.A.L. sings a song:

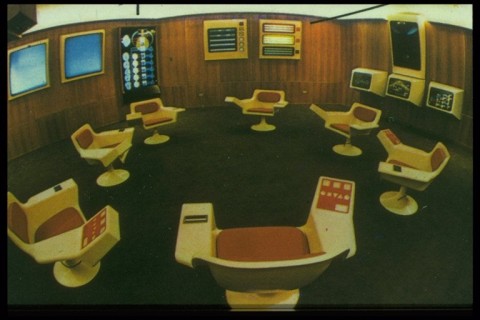

Not many people could afford an IBM 7094 computer back in the early 1960s — a typical installation cost $3 million. That’s the equivalent of around $20 million in purchasing power today. Over the course of the decade, fewer than 300 were built.

You didn’t get much computing power for that hefty price tag, at least by current-day standards. But if you wanted a machine that did complex or rapid math, you had few other options. The 7094 could handle 250,000 additions or subtractions in just one second. A whole room of accountants couldn’t keep up with it.

But addition and subtraction aren’t very sexy. So someone got the bright idea of teaching the IBM 7094 to sing. That’s why John L. Kelly Jr., Carol Lockbaum, and Lou Gerstman of Bell Labs, in Murray Hill, New Jersey, began working in 1961 on this pioneering computer music project.

Digital music wasn’t an entirely new development, even in those distant days, but singing presented completely different challenges, requiring breakthroughs in speech synthesis. But Bell Labs — then the in-house research arm of AT&T (it’s now part of Nokia) — had more expertise in that area than any other organization in the world.

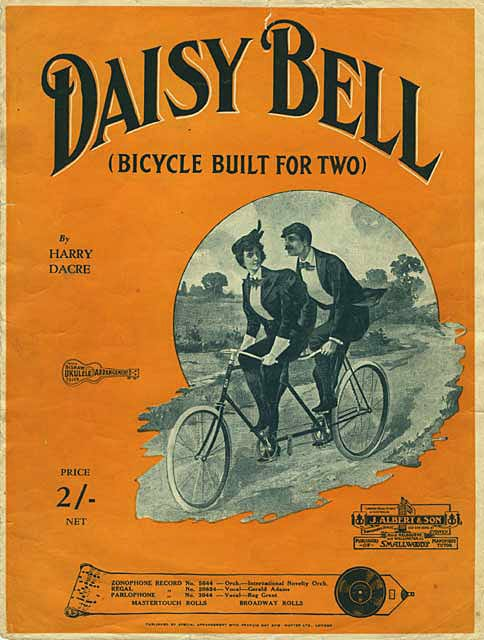

The Bell Labs team needed a song for their experiment. They decided on “Daisy Bell” — also known as “Bicycle Built for Two” — composed by British tunesmith Harry Dacre in 1892.

The idea for the song came to Dacre when he visited the US and found, to his surprise, that the customs officials had imposed a tariff on his bicycle. A friend quipped that he was lucky it wasn’t a bicycle with two seats, or the duty might have been double. The end result was Dacre’s most successful song ever.

[…]

Even back in the early 1960s, this tune didn’t have much hipness potential. But at least the melody was simple, well-known, and no longer protected by copyright. (That said, I would love to watch a jury in 1961 debate computer music rights.)

For the instrumental parts of the song, the Bell Labs team relied on contributions from Max Matthews, who had created a breakthrough sound-generating program called MUSIC back in 1957. In those ancient analog days, he had hooked up his violin to an IBM 704, and was thus the first performer in history to transfer live music to a computer for synthesis and playback.