canmildoc

Published on 17 Sep 2011Part 1 of 5

Documentary “Stories from the Second World War: Bloody Normany”.

Juno or Juno Beach was one of five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, during the Second World War. The sector spanned from Saint-Aubin, a village just east of the British Gold sector, to Courseulles, just west of the British Sword sector. The Juno landings were judged necessary to provide flanking support to the British drive on Caen from Sword, as well as to capture the German airfield at Carpiquet west of Caen. Taking Juno was the responsibility of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and commandos of the Royal Marines, with support from Naval Force J, the Juno contingent of the invasion fleet, including ships of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). The beach was defended by two battalions of the German 716th Infantry Division, with elements of the 21st Panzer Division held in reserve near Caen.

The invasion plan called for two brigades of the 3rd Canadian Division to land in two subsectors — Mike and Nan — focusing on Courseulles, Bernières, and Saint-Aubin. It was hoped that preliminary naval and air bombardment would soften up the beach defences and destroy coastal strongpoints. Close support on the beaches was to be provided by amphibious tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. Once the landing zones were secured, the plan called for the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade to land reserve battalions and deploy inland, the Royal Marine commandos to establish contact with the British 3rd Infantry Division on Sword, and the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade to link up with the British 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division on Gold. The 3rd Canadian Division’s D-Day objectives were to capture Carpiquet Airfield and reach the Caen-Bayeux railway line by nightfall.

The landings initially encountered heavy resistance from the German 716th Division; the preliminary bombardment proved less effective than had been hoped, and rough weather forced the first wave to be delayed until 07:35. Several assault companies — notably those of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada — took heavy casualties in the opening minutes of the first wave. Strength of numbers, as well as coordinated fire support from artillery and armoured squadrons, cleared most of the coastal defences within two hours of landing. The reserves of the 7th and 8th brigades began deploying at 08:30 (along with the Royal Marines), while the 9th Brigade began its deployment at 11:40.

The subsequent push inland towards Carpiquet and the Caen-Bayeux railway line achieved mixed results. The sheer numbers of men and vehicles on the beaches created lengthy delays between the landing of the 9th Brigade and the beginning of substantive attacks to the south. The 7th Brigade encountered heavy initial opposition before pushing south and making contact with the 50th Infantry Division at Creully. The 8th Brigade encountered heavy resistance from a battalion of the 716th at Tailleville, while the 9th Brigade deployed towards Carpiquet early in the evening. Resistance in Saint-Aubin prevented the Royal Marines from establishing contact with the British 3rd Division on Sword. When all operations on the Anglo-Canadian front were ordered to halt at 21:00, only one unit had reached its D-Day objective, but the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division had succeeded in pushing farther inland than any other landing force on D-Day. – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juno_beach

June 6, 2019

Bloody Normandy: Juno Beach and Beyond – Part 1

April 17, 2019

Tank Chats #46 Ram Kangaroo | The Funnies | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published on 16 Feb 2018As part of the Funnies mini-series, David Fletcher takes a look at the troop-carrying Ram Kangaroo.

Towards the end of World War Two, Canadian Ram tanks were converted into Armoured Personnel Carriers called Kangaroos.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Or donate http://tankmuseum.org/support-us/donateVisit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►https://tankmuseumshop.org/

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/ #tankmuseum #tanks

June 6, 2018

D-Day: Canada at Juno Beach

Yesterday Today

Published on 3 Jun 2017D-Day: Canada at Juno Beach

6 June 1944

Of the nearly 150,000 Allied troops who landed or parachuted onto the Normandy coast, 14,000 were Canadians. They assaulted a beachfront code-named “Juno”.

The Royal Canadian Navy contributed 110 ships & 10,000 sailors in support of the landings while the RCAF had helped prepare the invasion by bombing targets inland. On D-Day & during the ensuing campaign, 15 RCAF fighter & fighter-bomber squadrons helped control the skies over Normandy and attacked enemy targets. On D-Day, Canadians suffered 1074 casualties, including 359 killed.

April 15, 2018

Canada’s military – the difference between fighting wars in the 20th Century and fighting wars today

In a post from earlier this week about defence spending priorities for the Canadian military, Ted Campbell looks at how wars changed between the first half of the 20th century and the post-Cold War situation we face today:

In a post from earlier this week about defence spending priorities for the Canadian military, Ted Campbell looks at how wars changed between the first half of the 20th century and the post-Cold War situation we face today:

Is the 2% goal wrong?

No … it’s a pretty sensible level of defence spending for countries that really want to maintain a world at peace, as opposed to those, like Canada and many of its allies, that just want to hope for peace. But 2% is not a magic bullet … 1.5% of GDP, spent carefully, will do more than 2% spent as a job creation slush fund. But spending too little, cutting defence spending again and again and again just because it is unpopular can leave a country with what I have described as a Potemkin Village, a military that is more show than force.

The advent of a nuclear face-off circa 1950 changed the strategic calculus for the rest of the 20th century. We suddenly had the “come as you are war” which meant having regular, professional forces in being and not being able to rely upon time and space to give us time, as we had in past wars, to mobilize our reserves. We would do well, 101 years after the battle of Vimy Ridge, to recall that it, in April 1917, was the first time since war was declared (in the summer of 1914) that the full Canadian Corps, of four infantry divisions, was in battle as a corps ~ it took us over 30 months to get from a tiny standing army backed by small but eager reserves to a full corps composed of about 100,000 of the Canadians who served overseas during that war. We went to war again in the late summer of 1939 and it was not until the summer of 1943, over 40 months later, that we had a small corps, of only two divisions and an independent armoured brigade, in battle, in Italy. It takes a long time to mobilize and equip and train an army. The operational doctrine of the long and expensive cold war said that we could no longer have that time.

It is not clear that we must or even should still have small reserves and a relatively larger permanent force. Perhaps the time has come to re-examine the assumptions that underlie our force structure ideas. Maybe we need 150,000 uniformed people but, maybe, the split should be 50/50 or 75,000 full time and 75,000 part time sailors, soldiers and air force members. Maybe a country like Canada, with a population that will, in 2050, approach 40 million, should have a larger force: say 75,000 full time and even 150,000 part time military members … maybe our reserve force “regiments’ should have 500 or 750 soldiers and be required to “generate” a trained company (125 soldiers) rather than having only 150 soldiers and being hard pressed to “generate” a platoon of only 30 soldiers. I have my own ideas, but someone who has the necessary information at their disposal needs to look ahead at our strategic situation and develop a force model and a sane budget for 2050. That should be a job for skilled civil servants in the defence policy staff.

Our strategic priorities for the next 30 years or more need to be:

- Containing and reducing threats to global peace and security by helping to maintain alliances like NATO and groupings like AUSCANNZUKUS and supporting global peacemaking and peacekeeping efforts, even the generally worthless United Nations efforts;

- Confronting current threats to peace ~ like Russia ~ and deterring (by matching the growth in military power of) potential future threats ~ like China;

- Cooperating with the USA in the protection of North America; and

- Securing the land we claim as our own, the waters contiguous to it and the airspace over both.

When we work out the costs, of people, above all, but also of ships, tanks, guns and aircraft, and of ammunition, food and fuel and everything else, of doing those four things ~ and of doing them well enough ~ then we will know what what sort of forces we need and how much we must budget to build and maintain them. But no matter what the size and what the cost, I guarantee that people will still be the biggest single expense if we keep our priorities straight: and the overarching priority is that people cost more than machines because they matter more than machines.

August 23, 2017

One definite success from the Dieppe raid

The allied attack on Dieppe in August, 1942 was an operational failure: nearly 60% of the raiding force were killed, wounded or captured and the tactical objectives in the harbour area were not achieved. I’ve mentioned the speculations on an Enigma side-operation (which does not seem to be given credence by most historians), using the main Canadian attack as cover for an attempt to snatch the latest German encryption device from one or more high-security locations within the target area. A second side-mission was also conducted to capture one of the newest German radar stations at Pourville, just down the coast from Dieppe:

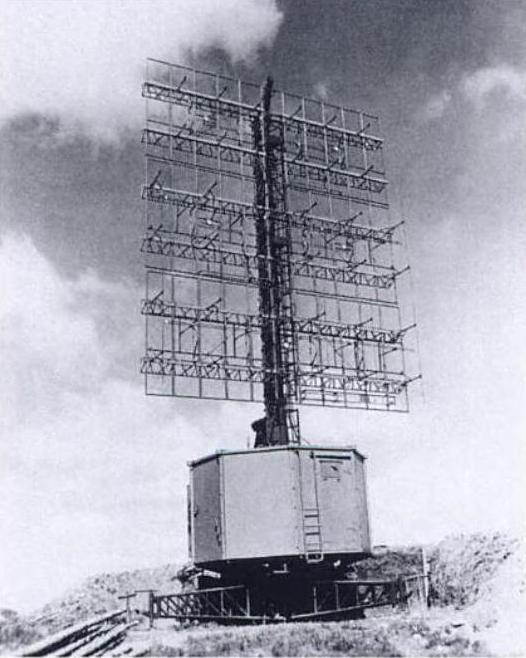

Aerial reconnaissance photos indicated that one of these new Freya radar sets had been installed at Pourville-sur-Mer, near Dieppe. A military raid on Dieppe, to test British and Canadian plans for an amphibious invasion, was already being planned. Senior officers immediately added a sub-plan to the Dieppe raid: a small force would be detached to attack the Pourville radar station. There, a radar expert would dismantle the station’s vital equipment and transport it back to the UK for analysis.

Nissenthall, a Jewish cockney who had a lifelong fascination with electronics and radio technology, had joined the Air Force as an apprentice in 1936. By the outbreak of the war in 1939 he was assigned to RAF radio direction finding stations (RDF, the short-lived original term for radar) and rapidly built up a reputation as a competent and technically skilled operator. Before the war he had also worked directly with Robert Watson-Watt, widely regarded today as the father of radar.A German FuMG 401 “Freya LZ” radar station of the type installed at Pourville. (US National Archives and Records Administration image, via Wikimedia)

[…]

More than 5,000 soldiers of the First Canadian Division set off from the south coast of England in the early hours of 19 August 1942. Embedded with A Company of the South Saskatchewan Regiment, Nissenthall’s 11-man bodyguard landed on French soil – but on the wrong side of the Scie River from the radar station.

After finding their way to their intended starting point, the team ran into stiff German resistance. Casualties soon mounted up as they probed the area, looking for a way into the radar station.

Thanks to the Bruneval raid six months previously, the Germans had beefed up their defences around coastal radar stations. This, combined with the naivete of the Allied planners back in Britain, had left the Canadians exposed and vulnerable. Though Nissenthall’s team had just about reached the radar station, there was no hope they would be able to get inside it, much less examine it, dismantle it and take away the most valuable parts of the Freya set inside.

August 19, 2017

Dieppe Raid 19 August, 1942 – Assault, escape and aftermath

Published on 22 Mar 2009

The Dieppe Raid was one of the costliest days for the Canadian Army in the entire Second World War. 907 Canadians were killed, in addition more than 2,500 were wounded or captured, all on August 19 of 1942.

At the BBC site: Julian Thompson’s summary of the Dieppe Raid.

October 15, 2015

S.L.A. Marshall, Dave Grossman, and the “man is naturally peaceful” meme

The American military historian S.L.A. Marshall was perhaps best known for his book Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command in Future War, where he argued that American military training was insufficient to overcome most men’s natural hesitation to take another human life, even in intense combat situations. Dave Grossman is a modern military author who draws much of his conclusions from the initial work of Marshall. Grossman’s case is presented in his book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, which was reviewed by Robert Engen in an older issue of the Canadian Military Journal:

As a military historian, I am instinctively skeptical of any work or theory that claims to overturn all existing scholarship – indeed, overturn an entire academic discipline – in one fell swoop. In academic history, the field normally expands and evolves incrementally, based upon new research, rather than being completely overthrown periodically. While it is not impossible for such a revolution to take place and become accepted, extraordinary new research and evidence would need to be presented to back up these claims. Simply put, Grossman’s On Killing and its succeeding “killology” literature represent a potential revolution for military history, if his claims can stand up to scrutiny – especially the claim that throughout human history, most soldiers and people have been unable to kill one another.

I will be the first to acknowledge that Grossman has made positive contributions to the discipline. On Combat, in particular, contains wonderful insights on the physiology of combat that bear further study and incorporation within the discipline. However, Grossman’s current “killology” literature contains some serious problems, and there are some worrying flaws in the theories that are being preached as truth to the men and women of the Canadian Forces. Although much of Grossman’s work is credible, his proposed theories on the inability of human beings to kill one another, while optimistic, are not sufficiently reinforced to warrant uncritical acceptance. A reassessment of the value that this material holds for the Canadian military is necessary.

The evidence seems to indicate that, contrary to Grossman’s ideas, killing is a natural, if difficult, part of human behaviour, and that killology’s belief that soldiers and the population at large are only being able to kill as part of programmed behaviour (or as a symptom of mental illness) hinders our understanding of the actualities of warfare. A flawed understanding of how and why soldiers can kill is no more helpful to the study of military history than it is to practitioners of the military profession. More research in this area is required, and On Killing and On Combat should be treated as the starting points, rather than the culmination, of this process.

June 6, 2015

Canada at War – Normandy, June 1944

Uploaded on 10 Jan 2012

Part 1 of 3

June – September 1944. D-Day, June 6, 1944. In the early morning hours, infantry carriers, including 110 ships of the Royal Canadian Navy, cross a seething, pitching sea to the coast of France, while Allied air forces pound enemy positions from the air. Cherbourg, Caen, Carpiquet, Falaise, Paris are liberated. Canadians return, this time victorious, to the beaches of Dieppe.

H/T to Gods of the Copybook Headings for the link.

May 10, 2015

In the Netherlands, 1945, nobody “swaggered”

David Warren on the task of the First Canadian Army after liberating The Netherlands:

It wasn’t only the liberation, but what our boys did after, in that devastated country. The Netherlands — but Canadians call her “Holland” — had suffered proportionally more than any other country the Wehrmacht had crushed and occupied, and would continue to suffer — famine — after their final defeat. The bastards blew the dikes to slow our allied advance. Breached, the lands flooded; … deaths heaped on deaths.

Victory is sweet, but there was no swagger, from the Dutch still mired in Hell.

And memorably, neither from our boys, who had liberated them. They didn’t swagger. Instead, they set down their guns and their helmets and went to work — spontaneously, voluntarily, on the enormous task of repair; of fixing the dikes and clearing the farms of salt-mud and debris. Of breaking the stones, and smoothing the roads, and shifting the rubble. The food bags, too, were starting to arrive, from Canada and the States — the tins and boxes; the cigarettes and medical supplies; and the candy, for the little children.

This wasn’t the Marshall Plan. It was three years before that. The Royal Canadian Air Force was dropping food from the sky, as fast as it could. (Our pilots read, “Thank you Canadians!” on rooftops.) Crates and drums were being discharged through the busted ports, wheat and flour from our Prairies. Yet thousands were still perishing from hunger.

And more: all the stuff sent by unorganized people, to wherever they thought it would do some good; to Germany as well as Holland; to wherever people must be desperate and starving. And back home our boys’ own families were throwing themselves into action, packing and shipping; and slipping in the letters of love and encouragement to strangers and new friends over the sea.

We were already hand-in-glove with the Dutch, from sheltering their royal family in exile. The magnificent Queen Wilhelmina, scourge of politicians (Churchill called her “the only real man” among all the exiled governors in London), no longer speaking in the nights, through the radio. For she had returned, to a rapturous welcome. And now, too, their little princess — Margriet Francisca — born in Ottawa Civic Hospital, in a maternity ward that had been declared Dutch sovereign territory for the occasion.

Every year, the tulips still come from Holland to decorate our Parliament Hill. And Dutch kids are still taught in school how to sing, “O Canada.”

December 27, 2014

Who should have been the allied commanders on D-Day?

Nigel Davies ventures into alternatives again, this time looking at who were the best allied generals for the D-Day invasion (for the record, he’s quite right about the best Canadian corps commander):

The truth is that any successful high command should maximise the chances of success of any campaign by choosing the ‘best fit’ for the job.

But that is not how generals were chosen for D Day.

(I would love to start with divisional commanders, but there are way too many, so for space I will start with Corps and Army commanders, and work up to the top).

The outstanding Canadian of the campaign for instance was Guy Simonds. Described by many as the best Allied Corps commander in France, and credited with re-invigorating the Canadian Army HQ when he filled in while his less successful superior Harry Crerar was sick, Simonds was undoubtedly the standout Canadian officer in both Italy and France.Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps.

He was however, the youngest Canadian division, corps or army commander, and the speed of his promotions pushed him past many superiors. He was also described as ‘cold and uninspiring’ even by those who called him ‘innovative and hard driving’. It can be taken as a two edged sword that Montgomery thought he was excellent (presumably implying Montgomery like qualities?) But his promotions seemed more related to ability than cronyism, and his achievements were undoubted.

Should he have been the Canadian Army commander instead of Crerar? Yes. Arguments against were mainly his lack of seniority, and lack of experience. but no Canadian had more experience, and lack of seniority was no bar in most of the other Allied armies.

It comes down to the simple fact that the Allied cause would have been better served by having Simonds in charge of Canadian forces than Crerar.

Simonds was a brilliant corps commander and (at least) a very good army commander, but he had one fatal flaw: he was no politician. Harry Crerar was a very “political” general, and played the political game with far greater talent than any other Canadian general. That got him into his role as army commander and his political skills kept him there despite the better “military” options available.

February 25, 2014

Official launch of the Laurier Military History Archive

A post at the Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies website introduces a digitized collection of maps, unit diaries, and other Canadian military history artifacts:

The Laurier Military History Archive – www.lmharchive.ca – is a project that was initiated in the Summer of 2013 by the Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies (LCMSDS), at Wilfrid Laurier University (Waterloo, Ontario). It offers the public previously unavailable access to a variety of digitized materials from LCMSDS’ archival holdings, and will increasingly offer digitized materials in partnership with other archival institutions and private donors. At time of our official launch of the website we would like to draw your attention to three collections in particular which our dedicated volunteers have worked hard to make available to you.

The three featured collections are the Second World War Canadian Army Air Photos Collection, The George Lindsey Fonds, and The Canadian War Diaries of the Normandy Campaign Collection.

February 4, 2014

“Chateau” generals

Nigel Davies has written a long post about the British and American standard of generalship in the two world wars, which won’t win him very many American (or Canadian) fans. That being said, he’s certainly right about the Canadian generals of WW2:

Contention: American senior generals in World War II were as bad, and for the same reason, as British senior generals in World War I.

[…] the politicians (and I will include Kitchener here, as he was by this time a politician with a military background rather than a real general), had based their recruiting campaign on a trendy ‘new model’ citizens army, rather than use the well developed existing territorial reserve system that would have done a far better job. They new enthusiastic troops were considered incapable of the traditional fire and movement approach of professional troops (the type that the Germans reintroduced in 1918 with their ‘commando units’, and the British army was able to copy soon after with properly trained and combat experienced personnel). Instead the enthusiastic amateurs were considered too badly trained to do more than advance in long straight lines… straight into the meat grinder.

Having said that the generals blame for the results should be at the very least shared with their political masters, I am still willing to express dissatisfaction with the approach of Haig and many of his senior commanders. They were Chateau Generals in approach and in attitude. They drew lines on maps without adequately considering the terrain, issued impossible instructions without looking at the state of the ground, and ran completely inadequate communications that were far from capable of keeping track of, or controlling, a modern battlefield.

[…]

It was noticeable later in the war that the more successful armies were commanded by competent and imaginative officers who insisted on detailed planning; intensive and specific tactical planning and operational training (down to practicing assaults on purpose built life size models); and very close control of operations to ensure success. They had usually learned the hard way, and had matured as experienced and pro-active leaders.

Of course some of this improvement was simply advances in technology. Tanks to breakthrough; better artillery fire plans to support and reduce casualties; air observation to enhance control and assess responses; better communications (including radio’s) to facilitate flexibility on the ground; and a generally better trained and more experienced soldier; with much more skilled officers. It all helped. But a lot came down to the attitude of the generals who believed that you got up front, found out the truth, stayed in close contact, and reacted to changed circumstances as immediately as possible.

However, as the American army was late to the battlefront, Davies contends that the leaders merely recapitulated the first stages of the bloody learning experience as their British counterparts, but didn’t produce the innovative leadership to match the Germans:

The Americans arrived on the Western Front when the war was already won. Only a few thousand were there for the last big German push, and by the time the Allies were moving to their final offensives with real American numbers involved, the German army was a broken reed. Which means that most American officers had only a few weeks of combat experience, and almost all of it against a failing army which had little resilience left to offer the type of resistance that might have caused the inexperienced American officers to have to reconsider their theories from their quicky officer training courses. Even the professional military officers received, at best, only a couple of hints that their ideas might not be inevitably effective against a stronger opponent. Certainly not enough time to learn how to analyse and adapt to circumstances in serious combat.

Which is why the majority of highly recognised American higher commanders in World War II appear to be chateau generals.

[…]

Eisenhower’s mistakes in theatre commands in Italy and France were possibly no worse in results than Wilson’s ongoing problems with Greece (he led the ‘forlorn hopes’ of both 1941 and 1944 there), but Eisenhower failed far more spectacularly with the Italian surrender, the Broad Front strategy, and the Bulge, than Wilson ever did with far inferior resources. MacArthur’s failures are more readily compared with Percival than the successes of a man like Leese, and Nimitz is often referred to as one of the great captains of history, for defeating a navy that repeatedly sabotaged its own efforts in the Pacific theatre. (Often by people who haven’t seemed to have ever heard of Max Horton’s much harder victory against the ruthlessly efficient U-boat campaign in the Atlantic theatre).

Similarly it is fair to say that the American front line commanders most people have never heard of were hardly inferior to their famous British contemporaries. Eichelberger was as good a commander, and as good a co-operator in Allied operations, as Alexander ever was. Truscott was probably at least the equal of Montgomery, given the opportunity. (I suspect possibly even better actually, but who can say?) Simpson, in his brief few months at the front, impressed many British officers who had served for years under men as good as Slim. And Ridgway showed in his few months of active operations a level of skill and competence (not necessarily the same thing) that far more experienced men like O’Connor did not surpass.

Why do we hear about the American chateau generals in preference to their front line leaders? And why do we hear about the British front line leaders in preference to their back office superiors. I would say it is because the British had been through a learning process in WWI that the Americans had not.

And the Canadian angle? As I’ve noted before, the First Canadian Army (scroll down to the item on John A. English’s book) was not as combat-effective in WW2 as the Canadian Corps had been in the First World War. One of the most obvious failings was in the advance to Antwerp:

Note that the equivalent British debacle during that campaign was when the Canadian Army took Antwerp undamaged, but then stopped for a rest before cutting off the retreating Germans. The Germans quickly fortified the riverbanks leading to the port, keeping it out of use for months. This was a clear example of the Canadian generals inexperience, and Montgomery is at fault here for being too involved in the last attempt to break the Germans before Christmas — Market Garden — and not paying close enough attention to one of his Army commanders, who was not supervising his Corps commander, who was not chasing his divisional commander adequately. (No one is imune from such glitches in a fast moving campaign. Inexperience any where down the chain can cause big problems. But it is noticeable that Crerar’s failure did not get him the public acclaim Patton has enjoyed?) Crerar was a ‘political appointment’ by the Canadians (an ‘able administrator’, but militarily ‘mediocre’ according to most) who Montgomery considered to be as inferior in experience and attitude as many of the American ‘chateau leaders’ he would have put in the same basket. By contrast Monty was delighted when the more competent front line leaders – the Canadian Simonds and the American Simpson – were assigned to him instead. As in the cases of the Australian General Morshead or the Polish General Anders, Montgomery only cared about ability, not nationality. But as was the case with the Americans, all too many generals in most armies, including the British and German armies, lacked experience or ability.

Update, 13 February: Mark Collins linked to an earlier post that helpfully describes some of the problems with Canadian generalship in Europe:

The Canadian command style in WW II was even more stuck in the mud than the American. With a few exceptions (McNaughton, Burns, Crerar) most Canadian generals had little or no General Staff experience, and those that did were practitioners of a successful, for the earlier WW I time and place, doctrine based on set piece battles founded on the systematic and intensive use of artillery.

One virtue of the German system is that it allowed officers to make mistakes: it did not allow them to sit on their butts waiting for orders; it encouraged risk taking which often worked but sometimes ended in bloody disaster (indeed it’s amazing it didn’t in France in 1940).

Indeed comparing the Canadian Army in WWII with the German is very difficult. Both had to expand from a tiny base to their war-time peak, but the Germans began in 1933 (actually even before then); we didn’t really begin until 1940. The Germans lost the Great War and the Reichswehr gave serious thought to how to do better next time.

One thing underlying the British set piece battle approach and limited freedom for commanders – the one the Canadian Army followed – seems to have been their realization in the late 1930s that the British Army was simply not as good as its 1914 ancestor. That was partly because of the losses of promising junior officers who never made general [though that affected the Germans too], partly because of indifference to defence at the governmental level, and partly because the military lapsed all too happily back into “real soldiering” in the 20’s.

September 20, 2012

Rewriting a crucial moment in WW2: 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade on D+1

If you’re interested in the Canadian part of the D-Day landings and the days that followed, you’ll probably want to visit the Canadian Military History site:

Marc Milner’s Chapter, “No Ambush, No Defeat: The Advance of the Vanguard of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 7 June 1944″ in Canada and the Second World War: Essays in Honour of Terry Copp rewrites the history of 9 Brigade on D-Day+1. The defeat of 9 Brigade has always been used a prime example of the flawed nature of Allied leadership and combat capability and proof of the superior fighting skill of German forces. Milner challenges this assessment, arguing “the vanguard of 9 Brigade fought an enemy at least three times its size to a standstill, and did so largely without the crucial component of Anglo-Canadian doctrine: artillery support … in the process 9 Brigade met and defeated a portion of the panzer forces that the 3rd Canadian Division had been tasked with destroying. So maybe 9 Brigade did all right on D+1 after all.”

The revised chapter to the book has been made available as a freely downloadable PDF.

August 30, 2012

General A.G.L. McNaughton and the First Canadian Army

Randall Wakelam reviews a new biography of Lieutenant-General A.G.L. McNaughton, the first commander of Canada’s major field formation in World War 2:

Lieutenant-General A.G.L. ‘Andy’ McNaughton was one of the key staff gunners in the Canadian Corps in the Great War and went on to be Chief of the General Staff in Ottawa from 1930 to 1935. From 1935 to 1939 he established and led the National Research Council. He was recalled to active service in 1939 and took 1st Canadian Division overseas. Once there he would spend four years building the Canadian field force first to corps and then army level. Relieved of army command in late 1943, he was for a short while Minister of National Defence and in the postwar years continued to serve Canada as the Canadian co-chair of the Canada-US Permanent Joint Board on Defence. Not a bad record of public service, but he is most remembered for his apparent failures as general officer commanding-in-chief (GOC-in-C), First Canadian Army.

[. . .]

Previous portraits show McNaughton to be a general who argued vehemently against breaking up his force for errant missions and, who at the same time, was a failure in field exercises. He has also been seen as an inflexible man who could not get on with his military or political seniors. Historians of no less repute than C.P. Stacey, Jack English and Jack Granatstein have created that portrait for Andy.

[. . .]

Rickard has gone well beyond what we have to now generally accepted as the tragic character that was Andy McNaughton. He has drawn from an impressive range or primary sources in building a case for, if not accepting McNaughton as a viable, but unlucky commander, then one whose flaws are now better understood in comparison of those of his peers. While not all will agree with Rickard’s assessment of McNaughton it could be argued that such disagreement is born in large part because of the complex nature of high command and the management of armies and national forces in coalition warfare – what might be termed Clausewitzian fog and friction both on the battlefield and in the meeting rooms, and with more than a pinch of ambiguity added when it comes to strategic-level discussions and decisions. Such has been the case recently for Canadian politicians and commanders in Afghanistan and the Mediterranean; both they and students of Canadian history will enjoy John Rickard’s fresh and refreshing study of Andy.

February 27, 2011

Sunday book post

No, not my books: I’ve written lots, but they’re all technical manuals for software products the vast majority of you will never have heard of, and wouldn’t want to read about even if you had. I mean books I’ve read recently that I consider to be very good. I’ll categorize for convenience (both yours and mine):

Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Darwin’s Watch: The Science of Discworld III, Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen. An entertaining romp through (real) science placed within a fictional context. I read the first Science of Discworld book and quite enjoyed it, and this one is possibly even better. The Discworld, riding happily balanced on the backs of the four great elephants, who are in turn supported by the shell of the great turtle, has very different scientific principles than our own “exotic” roundworld. The most amusing part of the book is the wizards of the Unseen University attempting to ensure that Charles Darwin writes the “correct” book on roundworld. You’ll learn more science than you expect . . .

- I Shall Wear Midnight, Terry Pratchett. The fourth of the Tiffany Aching sequence in the Discworld series. Although written for a younger audience, Pratchett’s sense of humour and brilliant presentation make this book eminently readable for all ages.

- Cryoburn, Lois McMaster Bujold. The latest adventure of Miles Vorkosigan deals with the political and social implications of cryogenic preservation. No soaring battles in space, no stunner shootouts, no alien invasions. Sounds deadly dull, I realize, but I don’t think Lois could write a boring shopping list. It perhaps doesn’t stand alone quite as well as it might, but even if you haven’t read any of the other books in the series, I think you’ll find this worth reading.

History

- The Canadian Army and the Normandy Campaign, John A. English. A book that undermines several widely held beliefs about the efficiency and capability of the Canadian First Army in 1944-45. Between incompetent, scheming generals and political interference, the Canadian Army was less than the sum of its parts, and the importance of training methods and doctrine are highlighted (that is, the faulty training methods in use probably added to the casualty lists in combat). Field Marshal Montgomery didn’t like or trust General Harry Crerar, but was forced to keep him in command due to Canadian government sensitivities. Montgomery’s view of Crerar almost certainly was reflected in the roles assigned to First Canadian Army after the Normandy landings.

- The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, Edward N. Luttwak. A fascinating book about the differences between the Byzantine empire’s military and political goals and practices and those of the Roman empire from which it descended. Unlike Rome, the Byzantines were never the “superpower” of their part of the world, and their survival often depended on carefully constructed alliances, allies-of-convenience, and outright bribery of “enemies of their enemies”. Although not well remembered in the west, the survival of Byzantium almost certainly saved central Europe from conquest by the armies of the Caliph during the initial expansion of the Muslim empire. Byzantine armies rarely had much technological or doctrinal advantage over their opponents, so war had to be conducted with the key concept of retention of force: ambush, raid, counter-attack, feint, and misdirection became specialties because they offered (relative) effectiveness at lower risk of outright defeat.

- In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire, Adrian Goldsworthy. A selection of mini-biographies of some of the greatest generals of the Roman empire. What is amazing, in reading about some of their careers, is how little actual military instruction Roman officers received, yet how effective the army could be in spite of that. Being an army officer was viewed as just part of the normal public service — in fact, it would have been problematic for a Roman patrician to remain with the army for an extended period of time, as it would slow down his progress through the civil government ranks.

- The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5, Christopher Andrew. If you wanted a thrilling account of the exciting and dangerous life of counter-espionage, you need to stick to works of fiction. The actual life of an MI5 officer is apparently much less James Bond and much more careful investigation, observation, and data correlation. Not that it isn’t an interesting career, but perhaps the “double oh” agents will get their own book (just kidding).

Economics

- The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson. I enjoyed reading this one far more than I expected to: the author has a knack for carrying you through the less interesting bits without boring or lecturing you. The evolution of the modern monetary system, and the heroic roles played by unlikely characters in the process.

- The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves, Matt Ridley. It’s easy to find depressing statistics and dreary anecdotes. Ridley’s view is that progress is a good thing, and that we’re enjoying a golden age even if we don’t realize it right now.

Biography

- Robert A. Heinlein: In dialogue with his century Volume 1, William H. Patterson, Jr. I’ve been a huge fan of Heinlein’s works since I read Starship Troopers at about age 11. This biography more than met my expectations: I’d always regretted never having met Robert Heinlein, but between this book and Heinlein’s own autobiographical writings (Tramp Royale and Grumbles from the grave) I feel I’ve gotten as close to knowing him as possible — until the publication of Volume 2, anyway.

- Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, Christopher Hitchens. A lively appreciation of Thomas Paine’s most influential work, and much detail on his life. Paine was far from being the disreputable bomb-throwing anarchist his enemies painted him to be, but he also wasn’t the plaster saint his fans might imagine.

Wine

- Billy’s Best Bottles: Wines for 2011, Billy Munnelly. Still the best annual wine guide for the everyday wine drinker in Ontario. If you like an occasional bottle of wine, but don’t want to study dozens of books in order to make a decision on what to buy, this is the book for you. He likes more “rustic” wines than I do, so I don’t find his recommendations in that category to be as useful, but he does a great job of sorting through the plethora of $10-20 wines available at the LCBO and tells you which ones are worth buying (and when to serve them).