The central problem of relations with de Gaulle stemmed from President Roosevelt’s distrust. Roosevelt saw him as a potential dictator. This view had been encouraged by Admiral Leahy, formerly his ambassador to Marshal Petain in Vichy, as well as several influential Frenchmen in Washington, including Jean Monnet, later seen as the founding father of European unity.

Roosevelt had become so repelled by French politics that in February he suggested changing the plans for the post-war Allied occupation zones in Germany. He wanted the United States to take the northern half of the country, so that it could be resupplied through Hamburg rather than through France. “As I understand it,” Churchill wrote in reply, “your proposal arises from an aversion to undertaking police work in France and a fear that this might involve the stationing of US Forces in France over a long period.”

Roosevelt, and to a lesser extent Churchill, refused to recognize the problems of what de Gaulle himself described as “an insurrectional government”. De Gaulle was not merely trying to assure his own position. He needed to keep the rival factions together to save France from chaos after the liberation, perhaps even civil war. But the lofty and awkward de Gaulle, often to the despair of his own supporters, seemed almost to take a perverse pleasure in biting the American and British hands which fed him. De Gaulle had a totally Franco-centric view of everything. This included a supreme disdain for inconvenient facts, especially anything which might undermine the glory of France. Only de Gaulle could have written a history of the French army and manage to make no mention of the Battle of Waterloo.

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 5, 2014

QotD: Churchill, Roosevelt and de Gaulle

January 29, 2014

Pitching the New Deal through film – Gabriel Over the White House

I’d never heard of Gabriel Over the White House, so Jonah Goldberg‘s summary was quite interesting:

The legendary media tycoon William Randolph Hearst believed America needed a strongman and that Franklin D. Roosevelt would fit the bill. He ordered his newspapers to support FDR and the New Deal. At his direction, Hearst’s political allies rallied around Roosevelt at the Democratic convention, which some believe sealed the deal for Roosevelt’s nomination.

But all that wasn’t enough. Hearst also believed the voters had to be made to see what could be gained from a president with a free hand. So he financed the film Gabriel Over the White House, starring Walter Huston. The film depicts an FDR look-alike president who, after a coma-inducing car accident, is transformed from a passive Warren Harding type into a hands-on dictator. The reborn commander-in-chief suspends the Constitution, violently wipes out corruption, and revives the economy through a national socialist agenda. When Congress tries to impeach him, he dissolves Congress.

The Library of Congress summarizes the film nicely. “The good news: He reduces unemployment, lifts the country out of the Depression, battles gangsters and Congress, and brings about world peace. The bad news: He’s Mussolini.”

Hearst wanted to make sure the script got it right, so he sent it to what today might be called a script doctor, namely Roosevelt. FDR loved it, but he did have some changes, which Hearst eagerly accepted. A month into his first term, FDR sent Hearst a thank-you note. “I want to send you this line to tell you how pleased I am with the changes you made in Gabriel Over the White House,” Roosevelt wrote. “I think it is an intensely interesting picture and should do much to help.”

You can probably get the overall tone of the movie from this clip:

Even the editors at Wikipedia — hardly a hotbed of proto-fascists — describe it as “an example of totalitarian propaganda”:

Controversial since the time of its release, Gabriel Over the White House is widely acknowledged to be an example of totalitarian propaganda. Tweed, the author of the original novel, was a “liberal champion of government activism” and trusted adviser to David Lloyd George, the Liberal Prime Minister who brought Bismarck’s welfare state to the United Kingdom. The decision to buy the story was made by producer Walter Wanger, variously described as “a liberal Democrat” or a “liberal Hollywood mogul.” After two weeks of script preparation, Wanger secured the financial backing of media magnate William Randolph Hearst, one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s staunchest supporters, who had helped him get the Democratic presidential nomination and who enlisted his entire media empire to campaign for him. Hearst intended the film to be a tribute to FDR and an attack on previous Republican administrations.

Although an internal MGM synopsis had labeled the script “wildly reactionary and radical to the nth degree,” studio boss Louis B. Mayer “learned only when he attended the Glendale, California preview that Hammond gradually turns America into a dictatorship,” writes film historian Leonard J. Leff. “Mayer was furious, telling his lieutenant, ‘Put that picture back in its can, take it back to the studio, and lock it up!'”

Released only a few weeks after Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration, the film was labeled by The New Republic “a half-hearted plea for Fascism.” Its purpose, agreed The Nation, was “to convert innocent American movie audiences to a policy of fascist dictatorship in this country.” Newsweek‘s Jonathan Alter concurred in 2007 that the movie was meant to “prepare the public for a dictatorship,” as well as to be an instructional guide for FDR, who read the script during the campaign. He liked it so much that he took time during the hectic first weeks of his presidency to suggest several script rewrites that were incorporated into the film. “An aroma of fascism clung to the heavily edited release print,” according to Leff. Roosevelt saw an advance screening, writing, “I want to send you this line to tell you how pleased I am with the changes you made in Gabriel Over the White House. I think it is an intensely interesting picture and should do much to help.” Roosevelt saw the movie several times and enjoyed it. After a private screening, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote that “if a million unemployed marched on Washington … I’d do what the President does in the picture!”

Update, 5 November, 2018: James Lileks takes the opportunity to review this film on the eve of tomorrow’s US midterm elections.

For Election week, a remarkable movie. And I don’t mean “astonishingly good, technically superb, visually ingenious.” I mean utterly insane.

November 20, 2013

December 9, 2012

Sheldon Richman decries “Romanticizing Taxation”

Of all the topics you might try to romanticize, taxation would certainly be at the bottom of the list:

In the debate over avoiding the “fiscal cliff” — especially over whose taxes should and shouldn’t be raised — I detect an annoying attempt to romanticize taxation. I read this as an act of desperation on the part of those who want higher taxes on the wealthy, for there is nothing romantic about taxation.

The other day MSNBC’s Chris Hayes invoked Franklin Roosevelt in support of higher taxes on the top 2 percent. Pulling out all the stops, Hayes quoted from one of FDR’s October 1936 campaign speeches […]

Roosevelt’s claim that we can judge the social conscience of the government by how it collects taxes is true in a way he could not have imagined. Contrary to FDR and Justice Holmes, taxes are neither a price (in the voluntary-transaction sense) nor club dues. On the contrary, they are exactions by threat of violence. Some social conscience! How ironic that organized society and civilization itself are said to depend on the government’s threatening peaceful people if they fail to surrender their property as demanded by politicians who presumptuously and self-servingly claim to “represent” all the people.

Far from some enlightened institution, taxation began when conquerors realized that formal and continuing appropriation of a subject population’s wealth was preferable to hit-and-run pillaging. For this to work, however, the rulers needed to convince the peasants that the regime would protect them from predators in return for their regular remittances. That’s right: It was a protection racket, from which the racketeers and their cronies profited handsomely. For the taxpayers, there was little choice in the matter. They weren’t buying protection as people buy insurance in the market, and they weren’t paying dues as they would later pay dues to mutual-aid societies. They paid or they were punished. The ideology of benevolent state protection reduced enforcement costs because the ruled outnumbered the rulers and widespread tax resistance would have doomed the regime. Things have changed little in our time.

February 3, 2012

Reason.tv: A non-hagiographic analysis of FDR, the New Deal, and the expansion of federal power

August 7, 2011

November 4, 2010

Something I’m adding to my Christmas list

H.L. Mencken was a literary giant in the 1920s and into the 1930s, but fell from the pinnacle of popularity as the Great Depression hit. His consistent opposition to FDR and the New Deal moved him further and further away from the limelight, and his outspoken opposition to the war rendered him all but unpublishable from 1941 until his death. A large collection of his shorter works from 1914 through 1927 were published in Prejudices, running to six volumes.

The books are back in print, in two large volumes, through Library of America. An excerpt from the New York Review of Books just starts to get interesting before the cut-off for non-subscribers:

The material that H.L. Mencken published in a series of six volumes under the title Prejudices was a collection of his journalism written between 1914 and the late 1920s. Most of it, he told a good friend on publication of the first volume in 1919, was “light stuff” with an occasional “blast from the lower woodwind” that would “outrage the umbilicari, if that is the way to spell it.” Such books, he added, were “mere stinkpots, heaved occasionally to keep the animals perturbed.”

Most of the pieces in the first volume — or “series,” as it was called — had originally appeared in The Smart Set, the magazine he had edited since 1914, but they also included articles published in newspapers, as well as material written especially for the book. A painstaking editor of his own work, Mencken also did a good bit of rewriting; stinkpot or not, this was not to be a quick harum-scarum hustling of secondhand goods but a high-quality piece of prose from a master.

Its commercial success surprised him as well as his friend and publisher, Alfred Knopf, who seemed to realize for the first time that Mencken had a promising future, or, as he expressed it to his author, “that H.L. Mencken has become a good property.” The book was quickly followed by Prejudices: Series Two, Series Three, and so on to a final Series Six in 1927, by which time Mencken had developed from a good property into the most exciting literary figure in the country.

H/T to Mark at Unambiguously Ambidexterous for the link.

October 25, 2010

Amity Schlaes’ (condensed) The Forgotten Man

An article encapsulating some of the key points of Amity Schlaes’ The Forgotten Man in PDF form:

We all know the traditional narrative of that event: The stock market crash generated an economic Katrina. One in four was unemployed in the first few years. It resulted from a combination of monetary, banking, credit, international, and consumer confidence factors. The terrible thing about it was the duration of a high level of unemployment, which averaged in the mid teens for the entire decade.

The second thing we usually learn is that the Depression was mysterious — a problem that only experts with doctorates could solve. That is why FDR’s floating advisory group — Felix Frankfurter, Frances Perkins, George Warren, Marriner Eccles and Adolf Berle, among others — was sometimes known as a Brain Trust. The mystery had something to do with a shortage of money, we are told, and in the end, only a Brain Trust’s tinkering with the money supply saved us. The corollary to this view is that the government knows more than American business does about economics.

Another common presumption is that cleaning up Wall Street and getting rid of white-collar criminals helped the nation recover. A second is that property rights may still have mattered during the 1930s, but that they mattered less than government-created jobs, shoring up home-owners, and getting the money supply right. A third is that American democracy was threatened by the rise of a potential plutocracy, and that the Wagner Act of 1935 — which lent federal support to labor unions — was thus necessary and proper. Fourth and finally, the traditional view of the 1930s is that action by the government was good, whereas inaction would have been fatal. The economic crisis mandated any kind of action, no matter how far removed it might be from sound monetary policy. Along these lines the humorist Will Rogers wrote in 1933 that if Franklin Roosevelt had “burned down the capital, we would cheer and say, ‘Well at least we got a fire started, anyhow.’”

To put this official version of the 1930s in terms of the Monopoly board: The American economy was failing because there were too many top hats lording it about on the board, trying to establish a plutocracy, and because there was no bank to hand out money. Under FDR, the federal government became the bank and pulled America back to economic health.

When you go to research the 1930s, however, you find a different story. It is of course true that the early part of the Depression — the years upon which most economists have focused — was an economic Katrina. And a number of New

Deal measures provided lasting benefits for the economy. These include the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the push for free trade led by Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and the establishment of the modern mortgage format. But the remaining evidence contradicts the official narrative. Overall, it

can be said, government prevented recovery. Herbert Hoover was too active, not too passive — as the old stereotypes suggest — while Roosevelt and his New Deal policies impeded recovery as well, especially during the latter half of the decade.

H/T to Monty for the link.

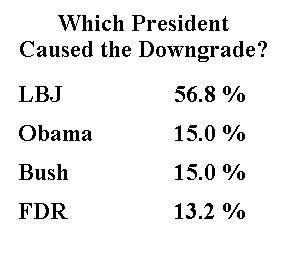

Well, it turns out that Social Security is a relatively minor part of the problem, so even though President Roosevelt’s policies exacerbated and extended the Great Depression, the program he created is only responsible for a small share of the fiscal crisis. To give the illusion of scientific exactitude, let’s assign FDR 13.2 percent of the blame.

Well, it turns out that Social Security is a relatively minor part of the problem, so even though President Roosevelt’s policies exacerbated and extended the Great Depression, the program he created is only responsible for a small share of the fiscal crisis. To give the illusion of scientific exactitude, let’s assign FDR 13.2 percent of the blame.