I never played Dungeons & Dragons when I was a child, or even a teenager. But a few years ago I became hooked listening to a podcast in which three brothers and their father played a simplified version of the game. I had always assumed it was a highly complex affair, with tomes of rules to master, impossibly-sided dice, and a multitude of maps and detailed figurines. But all of that is actually just optional. At root, it’s simply collective storytelling, with pre-agreed constraints on what you can and can’t do. There’s a reason it worked so well in a podcast — there’s actually nothing to see, only to hear. I’ve now run my own version of the game with a few close friends, and it hardly even requires pen and paper. Most of it is people just describing what they wish to do, and then rolling dice to see if they’re successful. It doesn’t even require dragons or dungeons — you could right now invent your own version set on another planet, in the future, or in the ancient world. The only limit is imagination. It’s infinitely modifiable. And it’s extremely fun.

So why were such games seemingly only invented in the 1970s? Humans have been telling stories presumably since we evolved to speak. We’ve been using dice, or something quite like them, since at least 3,000 BCE. Why did it take us so long to combine them? Certainly, some elements were already present in the mid-1820s in Kriegsspiel, a Prussian battle simulation game, in which regiments had hitpoints that needed to be depleted to remove them from the field, as well as an umpire — much like the later Dungeon Masters — to roll the dice and decide if players’ orders succeeded. Even the 1820s, however, seems rather late.

One of the responses I saw on Twitter was that such games required a bureaucratic mindset — that it’s an essentially modern thing to reduce attributes like health or skills or the strength of an attack to numerical values. Children (and adults) have always played at roles, of course. In ancient Egypt children had miniature wooden swords; in thirteenth-century England, even kings played at being Arthurian knights. But tabletop role-playing games require systematising and formalising that play. It’s not just saying “I pull out a sword and hack the goblin’s head off”. Instead, first roll this die to see if you succeed. But is this really so modern? Obsessive counting of things, at least in the English-speaking world, seems to date at least from the seventeenth century — perhaps it wasn’t that widespread, but lists like actuarial tables and demographic statistics were already being compiled. The craze in seventeenth-century English policy circles was for “political arithmetic”. All in all, if the lack of such an attitude even was a constraint, it seems a soft one. If the predominantly agrarian society of 1820s Prussia could come up with Kriegsspiel, why not earlier still?

Another response I got was that such games needed literacy or numeracy, or had something to do with printing. But the whole thing can be done, and indeed invented, with just pen and paper. It could even be done with chalk on slate, or with sticks in the sand. As for the counting elements of such games, they essentially involve just agreeing a number — your health in the story, for example, or your ability to attack — and then comparing it with another number, such as an opponent’s armour or their ability to attack. It barely requires numeracy, let alone literacy. Tallying would cover most of it. And, of course, games might still be popular among a smaller group of literate people, even if much of the overall population was illiterate. Again, it seems too soft a constraint.

Finally, there was the response that the invention of such games required higher population densities. But that would be an argument against the invention of all games. We’ve had chess for millennia, however, and card games for centuries. If anything, we’ve been storytelling for even longer. An interesting variant of the argument, suggested by Matt Clancy, is that in fact tabletop role-playing games have been invented and re-invented many times, all over the world, but because of the lack of printing and low population densities, they have become lost and forgotten. Perhaps. Though I find it hard to believe that an activity so fun would never have been mentioned.

Anton Howes, “Where Be Dragons?”, Age of Invention, 2020-02-13.

January 19, 2025

July 3, 2023

Schools fail their students when they try to teach things the students have no interest in learning

David Friedman has several examples of success in learning when the learner suddenly wants to learn the material:

One of the problems with our educational system is that it tries to teach people things that they have no interest in learning. There is a better way.

What started me thinking about the issue and persuaded me to write this post was an online essay, by a woman I know, describing how she used D&D to cure her math phobia.

How to Cure Mathphobia

I was failed by the education system, fell behind, never caught up, and was left with a panic response to the thought of interacting with any expression that has numbers and letters where I couldn’t immediately see what all of the numbers and letters were doing. The first time I took algebra one, I developed such a strong panic response that it wrapped around to the immediate need to go to sleep, like my brain had come up with a brilliant defense mechanism that left me with something akin to situational narcolepsy. (I did, actually, fall asleep in class several times, which had never happened to me before.) I retook the class the next year. I spent a lot of that year in tears, with a teacher who specifically refused to answer questions that weren’t more specific than “I don’t get it” or “I have no idea what any of those symbols mean or what we’re doing with them”.

Until she had a use for it:

The first time I played D&D, I was a high school student. My party was, incidentally, all female, apart from one girl’s boyfriend and the GM, who was the father of three of the players. We actually started out playing first edition AD&D, which I am almost tempted to recommend to beginners, just on the grounds that if you start there you will appreciate virtually every other edition of D&D you end up playing by comparison. I might have given up myself before I started, except that one of the players in the first game I ever spectated was a seven-year-old girl, and I was not about to claim that I couldn’t do something that a seven-year-old was handling just fine.

One of my most vivid memories of this group is the time we were on a massive zigzagging staircase — like one of those paths they have at the Grand Canyon, that zigzag back and forth down the cliff face so that anyone can reach the bottom without advanced rock-climbing. We saw a bunch of monsters coming for us from the ground below, and we weren’t sure whether they had climb speeds, but we didn’t super want to wait to find out. The ranger pulled out her bow to attack them before they could get to us.

“Now, wait a moment,” says the GM. “Can your arrows actually reach that far?”

“Well, they’re only, like, sixty feet away.”

“No, it’s more than that, because you have to think about height in addition to horizontal distance.”

“Yeah, but that’s, like, complicated?”

“Is it? Most of you are taking geometry right now, don’t you know how to find the hypotenuse of a right triangle?”

There were some groans. Math was hard. But we did know how to find the hypotenuse of a right triangle. We got out some scrap paper and puzzled over it for a couple minutes, volunteering the height of the cliff and the distance of the monsters and deciding that we could ignore the slight slope caused by the zigzagging stairways. We got a number back and compared it to the bow’s range per the rules. We determined that we could hit the monsters without a range penalty.

We killed the monsters. This wasn’t the real victory that day.

April 30, 2015

When Dungeons and Dragons met LEGO

A picture really can convey a thousand words:

I’ve often contend that three of the most significant influences on my adolescent years were: LEGO building, computer programming, and playing Dungeons & Dragons. With this latest mosaic project, I more or less bring all of those things together (the LEGO and D&D are obvious, while behind the scenes I have the software program I wrote to help me map out the whole mural).

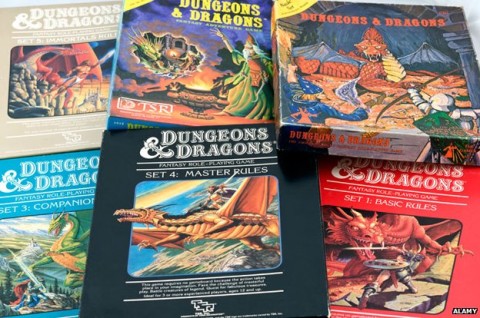

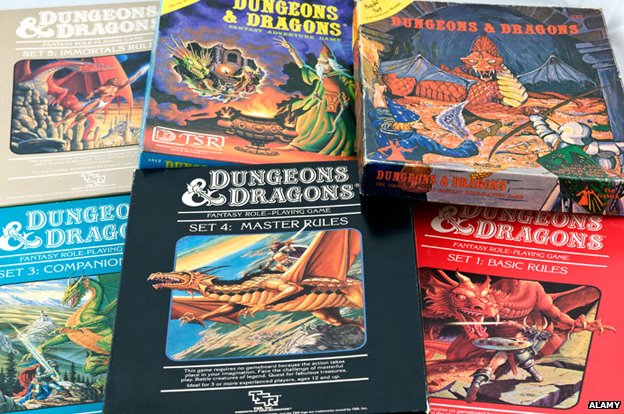

For those not quite as nerdy as myself, here’s the background on this image. It is the cover to the boxed set of the 1977 version on the game Dungeons & Dragons. This was the first version of the game released as the “Basic” set. It was the first set that my brother and I owned and played with. Obviously, the countless hours I spent reading the rulebook and perusing the illustrations made a pretty big impression on me. In fact, I still run a Basic D&D campaign semi-regularly using this very set.