Lindybeige

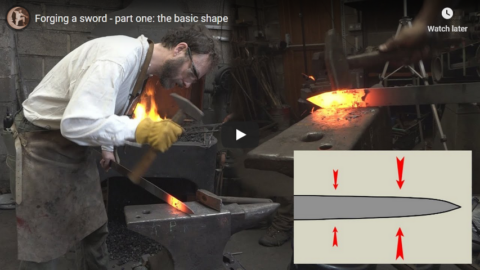

Published 8 Feb 2018Hammering hot metal into shape is quite a satisfying task, when it goes well. Here you see me shaping out my sword.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

I was invited by the Cut and Thrust Collective to go to Glastonbury and make my own sword. In an earlier video, you saw my training (forging a nail), and immediately after that we started on the sword. Thom Leworthy was the bladesmith showing me how it is done.

The Cut and Thrust Collective:

glastonburysmith@gmail.comBuy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

August 22, 2020

June 23, 2020

Defending Britain with a Bayonet | Hobart’s Pike | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 24 May 2020Director Richard Smith looks at Percy Hobart and the incredible weapon he was issued on joining the Home Guard at the start of WW2; a bayonet welded to a pole. Major General Percy Hobart commanded the 79th Armoured Division and gave the revolutionary, specialised tanks used on D-Day their nickname “Hobart’s Funnies”.

https://tankmuseumshop.org/

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP & become a Friend: ► https://tankmuseumshop.org/Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

June 21, 2020

A Tale of Two Swords

Atun-Shei Films

Published 19 Jun 2020Myles Standish and Benjamin Church were military commanders in 17th century colonial Massachusetts who lived a generation apart. Standish came over on the Mayflower, and commanded the militia of the Plymouth Pilgrims in the 1620s; Church lived his whole life in the New World, and led the crack troops that tracked down Metacomet, sachem of the Pokanoket Wampanoag, during King Philip’s War in the 1670s. Standish carried an elegant German rapier, while Church used a simple naval cutlass. What changed? And what story can these two swords tell about the men who wielded them?

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (Between now and October, all donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

#PlymouthPilgrims #KingPhilipsWar #AmericanHistory

Watch our film ALIEN, BABY! free with Prime ► http://a.co/d/3QjqOWv

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/atunsheifilms

Merch ► https://atun-sheifilms.bandcamp.com~REFERENCES~

[1] Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs: “Myles Standish, Born Where? (2010).” Sail 1620 https://web.archive.org/web/201011301…

[2] Nathaniel Philbrick: Mayflower (2006). Penguin Books, Page 59-60

[3] “Short Men ‘Not More Aggressive'” (2007). BBC News http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/65…

[4] Charles Francis Adams: The New English Canaan of Thomas Morton (1883). The Prince Society, Page 284 https://archive.org/details/newenglis…

[5] Philbrick, Page 164

[6] Philbrick, Page 151-152

[7] Benjamin Church: Entertaining Passages Relating to King Philip’s War, Tercentenary Edition (1975). Pequot Press, Page 67-73

[8] Church, Page 75

[9] Church, Page 105-106

[10] Church, Page 108

[11] Church, Page 140

[12] Lisa Brooks: Our Beloved Kin (2018). Yale University Press, Page 322

[13] Church, Page 142

[14] Douglas Edward Leach: Flintlock and Tomahawk (1958). Parnassus Imprints, Page 231

[15] Philbrick, Page 338

[16] Church, Page 170

[17] Leach, Page 237

[18] Brooks, Page 337

September 22, 2019

Gladius VS Spatha – Why Did The Empire Abandon The Gladius?

Metatron

Published on 11 Feb 2017If the famous Gladius/rectangular Scutum combo had proven to be so effective for so many centuries why did the Late Empire Romans choose to abandon it in favour of a spatha/round shield combination? Here is what I think.

Gladius was one Latin word for sword, and is used to represent the primary sword of Ancient Roman foot soldiers.

A fully equipped Roman legionary after the reforms of Gaius Marius was armed with a shield (scutum), one or two javelins (pila), a sword (gladius), often a dagger (pugio), and, perhaps in the later Empire period, darts (plumbatae). Conventionally, soldiers threw javelins to disable the enemy’s shields and disrupt enemy formations before engaging in close combat, for which they drew the gladius. A soldier generally led with the shield and thrust with the sword. All gladius types appear to have been suitable for cutting and chopping as well as thrusting.

Gladius is a Latin masculine second declension noun. Its (nominative and vocative) plural is gladiī. However, gladius in Latin refers to any sword, not specifically the modern definition of a gladius. The word appears in literature as early as the plays of Plautus (Casina, Rudens).

Modern English words derived from gladius include gladiator (“swordsman”) and gladiolus (“little sword”, from the diminutive form of gladius), a flowering plant with sword-shaped leaves.

Gladii were two-edged for cutting and had a tapered point for stabbing during thrusting. A solid grip was provided by a knobbed hilt added on, possibly with ridges for the fingers. Blade strength was achieved by welding together strips, in which case the sword had a channel down the center, or by fashioning a single piece of high-carbon steel, rhomboidal in cross-section. The owner’s name was often engraved or punched on the blade.

August 30, 2019

Is The Roman Gladius (Sword) Really That Good?

August 21, 2019

QotD: The cult of Japanese cultural superiority

The Forged in Fire people have a new show: Knife or Die. It’s hard to discuss, because I don’t want to ridicule anyone. Any person with a desire to compete can show up with a big knife, and they will turn you loose on an obstacle course of things to cut. The first episode featured a Caucasian man wearing an Aikido costume and running shoes. I am serious. He carried a katana or “samurai sword,” even though aikido guys aren’t taught how to fight with swords. He hit a block of ice with it, and it bent in the middle.

That was a major blow to the Japan cult. Katanas are supposed to cut concrete blocks! At least that’s what they say in the Tokyo airport gift shop.

Why does aikido attract troubled people with unrealistic expectations? A high school friend of mine took up aikido. The Internet says he runs a dojo now. He gave his life to aikido. Unfortunately, aikido has a serious problem: it doesn’t work at all. Sure, you can twist people’s wrists and immobilize them if they are stupid enough to give you their hands, but everyone who has tried aikido in the ring has had his behind handed to him in individually wrapped slices. I can’t understand devoting your life to a martial art which can be defeated easily by 95% of angry untrained drunks. Would you open a store that only sold appliances that didn’t work?

Here are the words that start every single aikido demonstration: “Give me your hand.”

People are enchanted by Japan. They think the Japanese have deep wisdom we lack. They do, and here it is: do your job well and treat your elders and your boss with respect. That’s about it; the rest is hocus pocus. There are no Japanese superpowers. There is no chi. Steven Seagal has never once used magical Japanese aikido to fight a real fight because he knows he would experience humiliating losses.

Forged in Fire has its funny moments, but Knife or Die is a little too ridiculous to lampoon. It’s almost sad. It’s probably dangerous, too. Untrained eccentrics swinging razor-sharp knives of unknown quality in a timed test are a recipe for deep wounds and severe blood loss. I would hate to be in the studio when half of a knife goes flying off at 60 miles per hour.

Steve, “Knives for Knaves”, Tools of Renewal, 2018-05-31.

August 13, 2019

Hands on with the Sutton Hoo sword I Curator’s Corner Season 5 Episode 1

The British Museum

Published on 5 Aug 2019Sue Brunning and her trusty foam sword (newly dubbed Flexcalibur by commentator Pipe2DevNull) are back for another sword story. This time Sue takes us up close and personal with one of the most famous swords ever discovered.

Sue has also written a blog about Sutton Hoo available here: https://bit.ly/2yQkfYV (there are lots of other great articles there too!)

#CuratorsCorner #SwordswithSue #SuttonHooSue

June 9, 2019

Making the legendary service Khukuri/Kukri of British Gurkhas – KHHI Nepal

KHHI Nepal

Published on 26 Mar 2018See how a scrap of steel is converted into a piece of mastery craft by our men @ duty. All bear hands, hard labor, years of experience and great skill. Pls enjoy it!!

Is the original 2016-17 British Gurkhas Issue issued to the new recruits as their training, exercise, utility and even as a combat knife.

Product link :

https://www.thekhukurihouse.com/2016-17-british-standard-issue-bsi-2-kukri#makingkhukuri #bsikukri #servicekukri #gurkhaknife

April 13, 2019

September 13, 2018

Broadsword and targe – how Highlanders fought

Lindybeige

Published on 22 Aug 2018A quick introduction to the use of this weapon combination, shot very quickly at Fight Camp 2018. Sorry about the background noise.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/LindybeigeThis was shot at the end of the last day, and I was a bit hoarse from shouting, camping, and beer. When the aircraft overhead gets very loud, I have added subtitles.

The targes we are using are the correct diameter, but the real things were a fair bit heavier, and offered some protection against even musketballs.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

June 16, 2018

The pilum – did legionaries carry one or two?

Lindybeige

Published on 24 Jul 2015I used to be a museum guide, and when showing people the mannequins dressed as Romans, I used to tell the visitors that legionaries carried two pila, as I had seen it pictured in modern books. I may have been wrong.

The pilum (plural ‘pila‘) was the standard throwing weapon of the Roman legions. Archaeologists has found weighted and unweighted versions of them, but were both types carried by every legionary?

The spark for this video was a discussion I had about the authenticity of a set of plastic model legionaries on the march. They were shown carrying one pilum and wearing lorica segmentata. I said that they should have two, but then found myself unable to back this up with evidence. Polybius, writing about the earlier period, with javelin-throwing velites, and the triarii at the back, says that the hastatii carried two types of pilum, but it isn’t perfectly clear whether he meant that the unit carried both types, or each individual man within them. For the later days of the classic legionary, with no velites in front of him, and lorica segmentata on his back, I have no evidence for two pila per man.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

February 4, 2018

Sword Bayonets – German Casualties – Jerusalem Occupation I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 3 Feb 2018Check our Podcast: http://bit.ly/MedievalismWW1Podcast

Chair of Wisdom Time! This week we talk about possibly fabricated German casualty numbers, the unwieldy WW1 bayonets and the reaction to the occupation of Jerusalem.

October 25, 2016

QotD: Viking weapons and combat techniques (from historical evidence and re-creation)

I expected to enjoy Dr. William Short’s Viking Weapons and Combat Techniques (Westholme Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-59416-076-9), and I was not disappointed. I am a historical fencer and martial artist who has spent many hours sparring with weapons very similar to those Dr. Short describes, and I have long had an active interest in the Viking era. I had previously read many of the primary saga sources (such as Njal’s Saga Egil’s Saga, and the Saga of Grettir the Strong) that Dr. Short mines for information on Viking weaponscraft, but I had not realized how informative they can be when the many descriptions of fights in them are set beside each other and correlated with the archeological evidence.

For those who don’t regularly follow my blog, my wife Cathy and I train in a fighting tradition based around sword and shield, rooted in southern Italian cut-and-thrust fencing from around 1500. It is a battlefield rather than a dueling style. Our training weapons simulate cut-and-thrust swords similar in weight and length to Viking-era weapons, usually cross-hilted but occasionally basket-hilted after the manner of a schiavona; our shields are round, bossless, and slightly smaller than Viking-era shields. We also learn to fight single-sword, two-sword, and with polearms and spears. The swordmaster’s family descended from Sicilo-Norman nobles; when some obvious Renaissance Italian overlays such as the basket hilts are lain aside, the continuity of our weapons with well-attested Norman patterns and with pre-Norman Viking weapons is clear and obvious. Thus my close interest in the subject matter of Dr. Short’s book.

Dr. Short provides an invaluable service by gathering all this literary evidence and juxtaposing it with pictures and reconstructions of Viking-age weapons, and with sequences of re-enactors experimenting with replicas. He is careful and scholarly in his approach, emphasizing the limits of the evidence and the occasional flat-out contradictions between saga and archeological evidence. I was pleased that he does not shy from citing his own and his colleagues’ direct physical experience with replica weapons as evidence; indeed, at many points in the text, .the techniques they found by exploring the affordances of these weapons struck me as instantly familiar from my own fighting experience.

Though Dr. Short attempts to draw some support for his reconstructions of techniques from the earliest surviving European manuals of arms, such as the Talhoffer book and Joachim Meyer’s Art of Combat, his own warnings that these are from a much later period and addressing very different weapons are apposite. Only the most tentative sort of guesses can be justified from them, and I frankly think Dr. Short’s book would have been as strong if those references were entirely omitted. I suspect they were added mostly as a gesture aimed at mollifying academics suspicious of combat re-enactment as an investigative technique, by giving them a more conventional sort of scholarship to mull over.

Indeed, if this book has any continuing flaw, I think it’s that Dr. Short ought to trust his martial-arts experience more. He puzzles, for example, at what I consider excessive length over the question of whether Vikings used “thumb-leader” cuts with the back edge of a sword. Based on my own martial-arts experience, I think we may take it for granted that a warrior culture will explore and routinely use every affordance of its weapons. The Vikings were, by all accounts, brutally pragmatic fighters; the limits of their technique were, I am certain, set only by the limits of their weapons. Thus, the right question, in my opinion, is less “What can we prove they did?” than “What affordances are implied by the most accurate possible reconstructions of the tools they fought with?”.

As an example of this sort of thinking, I don’t think there is any room for doubt that the Viking shield was used aggressively, with an active parrying technique — and to bind opponents’ weapons. To see this, compare it to the wall shields used by Roman legionaries and also in the later Renaissance along with longswords, or with the “heater”-style jousting shields of the High Medieval period. Compared to these, everything about the Viking design – the relatively light weight, the boss, the style of the handgrip – says it was designed to move. Dr. Short documents the fact that his crew of experimental re-enactors found themselves using active shield guards (indistinguishable, by the way from my school’s); I wish he had felt the confidence to assert flat-out that this is what the Vikings did with the shield because this is what the shield clearly wants to do…

Eric S. Raymond, “Dr. William Short’s ‘Viking Weapons and Combat’: A Review”, Armed and Dangerous, 2009-08-13.

September 17, 2016

QotD: Historical clangers in The Last Samurai

… the movie is seriously anti-historical in one respect; we are supposed to believe that traditionalist Samurai would disdain the use of firearms. In fact, traditional samurai loved firearms and found them a natural extension of their traditional role as horse archers. Samurai invented rolling volley fire three decades before Gustavus Adolphus, and improved the musket designs they imported from the Portuguese so effectively that for most of the 1600s they were actually making better guns than European armorers could produce.

But, of course, today’s Hollywood left thinks firearms are intrinsically eeeevil (especially firearms in the hands of anyone other than police and soldiers) so the virtuous rebel samurai had to eschew them. Besides being politically correct, this choice thickened the atmosphere of romantic doom around our heroes.

Another minor clanger in the depiction of samurai fighting: We are given scenes of samurai training to fight empty-hand and unarmored using modern martial-arts moves. In fact, in 1877 it is about a generation too early for this. Unarmed combat did not become a separate discipline with its own forms and schools until the very end of the nineteenth century. And when it did, it was based not on samurai disciplines but on peasant fighting methods from Okinawa and elsewhere that were used against samurai (this is why most exotic martial-arts weapons are actually agricultural tools).

In 1877, most samurai still would have thought unarmed-combat training a distraction from learning how to use the swords, muskets and bows that were their primary weapons systems. Only after the swords they preferred for close combat were finally banned did this attitude really change. But, hey, most moviegoers are unaware of these subtleties, so there had to be some chop-socky in the script to meet their expectations.

One other rewriting of martial history: we see samurai ceremoniously stabbing fallen opponents to death with a two-hand sword-thrust. In fact, this is not how it was done; real samurai delivered the coup de grace by decapitating their opponents, and then taking the head as a trophy.

No joke. Head-taking was such an important practice that there was a special term in Japanese for the art of properly dressing the hair on a severed head so that the little paper tag showing the deceased’s name and rank would be displayed to best advantage.

While the filmmakers were willing to show samurai killing the wounded, in other important respects they softened and Westernized the behavior of these people somewhat. Algren learned, correctly, that ‘samurai’ derives from a verb meaning “to serve”, but we are misled when the rebel leader speaks of “protecting the people”. In fact, noblesse oblige was not part of the Japanese worldview; samurai served not ‘the people’ but a particular daimyo, and the daimyo served the Emperor in theory and nobody but themselves in normal practice.

Eric S. Raymond, “The Last Samurai”, Armed and Dangerous, 2003-12-15.

January 13, 2016

The death of the duel

ESR has a theory on the rapid decline of the duelling culture that had lasted hundreds of years until the mid-19th century:

I’ve read all the scholarship on the history of dueling I can find in English. There isn’t much, and what there is mostly doesn’t seem to me to be very good. I’ve also read primary sources like dueling codes, and paid a historian’s attention to period literature.

I’m bringing this up now because I want to put a stake in the ground. I have a personal theory about why Europo-American dueling largely (though not entirely) died out between 1850 and 1900 that I think is at least as well justified as the conventional account, and I want to put it on record.

First, the undisputed facts: dueling began a steep decline in the early 1840s and was effectively extinct in English-speaking countries by 1870, with a partial exception for American frontier regions where it lasted two decades longer. Elsewhere in Europe the code duello retained some social force until World War I.

This was actually a rather swift end for a body of custom that had emerged in its modern form around 1500 but had roots in the judicial duels of the Dark Ages a thousand years before. The conventional accounts attribute it to a mix of two causes: (a) a broad change in moral sentiments about violence and civilized behavior, and (b) increasing assertion of a state monopoly on legal violence.

I don’t think these factors were entirely negligible, but I think there was something else going on that was at least as important, if not more so, and has been entirely missed by (other) historians. I first got to it when I noticed that the date of the early-Victorian law forbidding dueling by British military officers – 1844 – almost coincided with (following by perhaps a year or two) the general availability of percussion-cap pistols.

The dominant weapons of the “modern” duel of honor, as it emerged in the Renaissance from judicial and chivalric dueling, had always been swords and pistols. To get why percussion-cap pistols were a big deal, you have to understand that loose-powder pistols were terribly unreliable in damp weather and had a serious charge-containment problem that limited the amount of oomph they could put behind the ball.

This is why early-modern swashbucklers carried both swords and pistols; your danged pistol might very well simply not fire after exposure to damp northern European weather. It’s also why percussion-cap pistols, which seal the powder charge inside a brass casing, were first developed for naval use, the prototype being Sea Service pistols of the Napoleonic era. But there was a serious cost issue with those: each cap had to be made by hand at eye-watering expense.

Then, in the early 1840s, enterprising gunsmiths figured out how to mass-produce percussion caps with machines. And this, I believe, is what actually killed the duel. Here’s how it happened…