realtimehistory

Published 19 Jul 2021Support Glory & Defeat: https://realtimehistory.net/gloryandd…

After the failed revolution of 1848, the German states within the German confederation were still moving towards unification. This movement would come from the citizens this time though but from the top. Prussia’s chancellor Otto von Bismarck was using clever and aggressive diplomacy to outmaneuver his biggest German rival: Austria.

» OUR PODCAST

https://realtimehistory.net/podcast – interviews with historians and background info for the show.» LITERATURE

Arand, Tobias: 1870/71. Der Deutsch-Französische Krieg erzählt in Einzelschicksalen. Hamburg 2018

Bremm, Klaus-Jürgen: 1866. Bismarcks Krieg gegen die Habsburger. Darmstadt 2016

Buk-Swienty: Schlachtbank Düppel. Geschichte einer Schlacht. Hamburg 2015

Fesser, Gerd: Königgrätz – Sadowa. Bismarck Sieg über Österreich. Berlin 1994» SOURCES

Böhme, Helmuth (Hrsg.): Die Reichsgründung. dtv-Dokumente. München 1967Dollinger, Hans: Das Kaiserreich. Seine Geschichte in Texten, Bildern und Dokumenten. München, 1966

Hardtwig, Wolfgang /Hinze, Helmuth (Hrsg.): Deutsche Geschichte in Quellen und Darstellungen. Bd. 7: Vom Deutschen Bund zum Kaiserreich 1815 – 1871. Stuttgart 1997

Huber, Ernst Rudolf (Hrsg.): Dokumente der Verfassungsgeschichte, Bd. 2. 1851 – 1900. Stuttgart u.a. 1961

N.N.: Helmuth von Moltkes Briefe an seine Braut und Frau. Stuttgart u.a. 1911

Low, Sidney / Sanders Lloyd C.: The History of England During the Reign of Victoria (1837-1901) Volume 12 of 12, [Part of Series: The Political History of England in Twelve Volumes, Edited by William Hunt and Reginald L. Poole], Longmans, Green, and Co., London. 1907

» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias Arand, Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Battlefield Design

Research by: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias Arand

Fact checking: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias ArandChannel Design: Battlefield Design

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2021

August 9, 2021

The German Wars of Unification – Bismarck’s Rise I GLORY & DEFEAT

August 5, 2021

The Ems Dispatch – The Outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War I GLORY & Defeat Week 1

realtimehistory

Published 13 Jul 2021Support Glory & Defeat: https://realtimehistory.net/gloryandd…

French and Prussian animosity have been swelling in the background since the German Wars of Unification started in the 1860s. The French Duc de Gramont hopes that a victory over Prussia could restore French prestige while Prussian Chancellor Bismarck needs a reason to fulfill his dream of German unification from above. When the crisis about the Spanish throne escalates with the Ems Dispatch, the die is cast and the Franco-Prussian War begins.

» OUR PODCAST

https://realtimehistory.net/podcast – interviews with historians and background info for the show.» LITERATURE

Arand, Tobias: 1870/71 – Die Geschichte des Deutsch-Französischen Krieges erzählt in Einzelschicksalen. Hamburg 2018Böhme, Helmut: (Hrsg.): Die Reichs-gründung. dtv-Dokumente. München 1967

Gall, Lothar (Hrsg: Deutschland Archiv). Kaiserreich Bd. I. o.O. 2007

Girard Louis: Napoléon III. Paris 1986

Mährle, Wolfgang (Hrsg.): Nation im Siegesrausch. Württemberg und die Gründung des Deutschen Reiches 1870/71. Stuttgart 2020

Milza, Pierre: L’année terrible. La guerre franco-prussienne septembre 1870 – mars 1871. Paris 2009

» SOURCES

Fontane, Theodor: Der Krieg gegen Frankreich Bd. I. Berlin 1873Louis L. Snyder, ed., Documents of German History. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1958

» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Cathérine Pfauth, Dr. Tobias Arand, Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Battlefield Design

Research by: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias Arand

Fact checking: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias ArandChannel Design: Battlefield Design

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2021

July 30, 2021

QotD: Bismarck on history

A statesman has not to make history, but if ever in the events around him he hears the sweep of the mantle of God, then he must jump up and catch at its hem.

Otto von Bismarck

June 12, 2021

QotD: The assassination attempt(s) on Bismarck

… 19th-century history, particularly the years from the 1848 revolutions to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The key was Bismarck, the Prussian minister-president who unified Germany. If you want to learn about Bismarck, you will probably pick up a book by some historian of international relations, such as A.J.P. Taylor. That’s the right place to start. But it means you can read a lot about Bismarck before finding out about the time in May 1866 when a guy shot him.

Ferdinand Cohen-Blind, a Badenese student of pan-German sentiments, waylaid Bismarck with a pistol on the Unter den Linden. He fired five rounds. None missed. Three merely grazed his midsection, and two ricocheted off his ribs. He went home and ate a big lunch before letting himself be examined by a doctor.

But even the books that condescend to mention this triviality may not tell you about the other time a guy shot Bismarck: A young Catholic tried to kill him in July 1874, during the anti-Catholic Kulturkampf Bismarck had engineered, but only managed to score his right hand with a bullet.

The point is not that Bismarck was particularly hated, although he was. The point is that this period of European (and American) history was crawling with young, often solitary male terrorists, most of whom showed signs of mental disorder when caught and tried, and most of whom were attached to some prevailing utopian cause. They tended to be anarchists, nationalists or socialists, but the distinctions are not always clear, and were not thought particularly important. The 19th-century mind identified these young men as congenital conspirators. It emphasized what they had in common: social maladjustment, mania, an overwhelming sense of mission and, usually, a prior record of minor crimes.

[…]

Bismarck was not much of a democrat, but his example is instructive. He was so phlegmatic about being shot that he obtained both of the guns he had been shot with. He kept them in his desk, ready for use against a third guy with the same bright idea.

Colby Cosh, “Those old terrorist tendencies”, Maclean’s, 2014-12-07.

December 11, 2019

Franco-Prussian War | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published 4 Feb 2018What was the Franco Prussian War?

Our Website: https://www.thearmchairhistorian.com/

Our Twitter:

@ArmchairHistOur Discord:

https://discord.gg/Ppb2cUdSources:

https://www.britannica.com/event/Fran…

http://francoprussianwar.com/

http://history-world.org/franco_pruss…

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/e…

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/hist…

http://geacron.com/home-en/?v=m&lang=…Music: Music: Antonio Salieri: “Twenty six variations on La Folia de Spagna“

November 8, 2018

The Franco-Prussian War

Epic History

Published on 29 Dec 2015The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870 (19 July 1870 – 10 May 1871), was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the German states of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. The conflict was caused by Prussian ambitions to extend German unification. Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck planned to provoke a French attack in order to draw the southern German states — Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria and Hesse-Darmstadt — into an alliance with the North German Confederation dominated by Prussia.

December 4, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – Lies – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 2 Dec 2017We’ve wrapped up our series on Otto von Bismarck, but we’ve only touched on the first half of his life! Maybe someday we’ll get to come back. Until then, James answers questions and discusses errors in this episode of Lies!

November 21, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – VI: Germany! – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 18 Nov 2017You would think that capturing the Emperor of France would end the war, but… no. Who could Bismarck negotiate with? Eventually he forced an interim government to cave to his demands, and at the same time convinced the rest of the German states to unite with Prussia.

November 13, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – V: Prussia Ascendant – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 11 Nov 2017The northern German states now looked to Prussia for leadership, but that power brought increased attention from their enemies. Bismarck engineered a war with France by striking at Napoleon III’s pride and wound up winning a runaway victory to secure Prussia’s diplomatic power.

November 6, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – IV: The Iron Chancellor – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 4 Nov 2017Bismarck turned up the heat on his long-term plan to unite the German Confederation under Prussian leadership. He allied with Austria to seize a piece of disputed land, then maneuvered them into a war that he decisively won. Even an assassination attempt could not stop him.

October 30, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – III: Iron and Blood – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 28 Oct 2017Bismarck was just starting to get the hang of diplomacy when the throne of Prussia passed to a new Frederick Wilhelm who promptly sent him away to Russia. But then Bismarck got tapped to serve as the Head of Government and began pushing for his great project: the unification of Germany.

October 22, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – II: A Man of Great Ideas – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 21 Oct 20171848. Revolution swept Europe as the working class rose up to claim their freedoms from an oppressive ruling class. But as a member of that ruling class, Bismarck had some resistance to this movement. He channeled his wild energy into productive avenues, gradually becoming the man of realpolitik that we know today.

October 16, 2017

Otto von Bismarck – I: The Wildman Bismarck – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 13 Oct 2017Otto von Bismarck became the greatest statesman of a generation, but he began as an intransigent and irresponsible youth. He coasted through college, got himself thrown out of an early political appointment, and caused havoc with his divisive opinions during a meeting of parliament.

December 9, 2014

Colby Cosh on the recent “unprecedented” terror attacks

In his latest Maclean’s article, Colby Cosh talks about the recent “freelance” terror attacks on Canadian soil and points out that no matter what the reporters say, they’re hardly “unprecedented”:

There has been much discussion about how to think of the type of freelance Islamist terrorist that has recently begun to belabour Canada. What labels and metaphors are appropriate for such an unprecedented phenomenon? I possess the secret: It is not unprecedented. This has been kept a secret only through some odd mischance, some failure of attention that is hard to explain.

I discovered the secret through reading about 19th-century history, particularly the years from the 1848 revolutions to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The key was Bismarck, the Prussian minister-president who unified Germany. If you want to learn about Bismarck, you will probably pick up a book by some historian of international relations, such as A.J.P. Taylor. That’s the right place to start. But it means you can read a lot about Bismarck before finding out about the time in May 1866 when a guy shot him.

Ferdinand Cohen-Blind, a Badenese student of pan-German sentiments, waylaid Bismarck with a pistol on the Unter den Linden. He fired five rounds. None missed. Three merely grazed his midsection, and two ricocheted off his ribs. He went home and ate a big lunch before letting himself be examined by a doctor.

[…]

The point is not that Bismarck was particularly hated, although he was. The point is that this period of European (and American) history was crawling with young, often solitary male terrorists, most of whom showed signs of mental disorder when caught and tried, and most of whom were attached to some prevailing utopian cause. They tended to be anarchists, nationalists or socialists, but the distinctions are not always clear, and were not thought particularly important. The 19th-century mind identified these young men as congenital conspirators. It emphasized what they had in common: social maladjustment, mania, an overwhelming sense of mission and, usually, a prior record of minor crimes.

In my Origins of WW1 series, I quoted from The War That Ended Peace (which I still heartily recommend):

Margaret MacMillan describes the typical members of the Young Bosnians, who were of a type that we probably recognize more readily now than at any time since 1914:

[They] were mostly young Serb and Croat peasant boys who had left the countryside to study and work in the towns and cities of the Dual Monarchy and Serbia. While they had put on suits in place of their traditional dress and condemned the conservatism of their elders, they nevertheless found much in the modern world bewildering and disturbing. It is hard not to compare them to the extreme groups among Islamic fundamentalists such as Al Qaeda a century later. Like those later fanatics, the Young Bosnians were usually fiercely puritanical, despising such things as alcohol and sexual intercourse. They hated Austria-Hungary in part because they blamed it for corrupting its South Slav subjects. Few of the Young Bosnians had regular jobs. Rather they depended on handouts from their families, with whom they had usually quarreled. They shared their few possessions, slept on each other’s floors, and spent hours over a single cup of coffee in cheap cafés arguing about life and politics. They were idealistic, and passionately committed to liberating Bosnia from foreign rule and to building a new and fairer world. Strongly influenced by the great Russian revolutionaries and anarchists, the Young Bosnians believed that they could only achieve their goals through violence and, if necessary, the sacrifice of their own lives.

The “peaceful century” from the defeat of Napoleon to the outbreak of the First World War was far from peaceful — we only see it as such in contrast to the bloodbath of 1914-1918. And terrorists of a type we readily recognize from the front pages of the newspapers today were prefigured exactly by the anarchist revolutionaries of a century ago.

August 14, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part ten of a series)

We’re edging ever close to the start of the Great War (no, I don’t know exactly how many more parts this will take … but we’re more than halfway there, I think). You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here (now with hopefully helpful descriptions):

- Why it’s so difficult to answer the question “Who is to blame?”

- Looking back to 1814

- Bismarck, his life and works

- France isolated, Britain’s global responsibilities

- Austria, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkan quagmire

- The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- The First Balkan War

- The Second Balkan War

The Balkans were the setting for two major wars among the regional powers (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Rumania, and the Ottoman Empire), but the wars had not spread to the rest of the continent. This run of good luck was not going to last much longer. We turn our attention to Britain, France, and Russia … as unlikely a set of allies as you’d find in the 1880s, now in the process of discovering a common threat in Europe.

Sir Edward Grey and Britain’s progress from “splendid isolation” to official ambivalence

The British government had spent most of the previous century staying out of continental disputes, only rarely becoming politically or militarily involved. Late in the nineteenth century, this began to change, and Britain started paying closer attention to what was happening on the continent and moving slowly toward re-engagement. While the British and the French had spent more time as enemies or as mutually distrustful neutrals, France was now looking across the Channel for much more than mere neutrality.

Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary 1905-1916

Sir Edward Grey had become foreign secretary on the formation of the Liberal government in December 1905, and remained in post until the end of 1916, so becoming the longest-serving holder of the post. Sir Edward brought diplomatic gravitas to his work in 1914. He had already convened the meeting of ambassadors that had contained and concluded the two Balkan wars of 1912-13. When the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on June 28 prompted a third Balkan crisis, it seemed unlikely to have any direct effect on British interests, but Sir Edward might still prove central to its resolution. If the “concert of Europe”, the international order created in 1814-15 after the Napoleonic wars, still had life, the foreign secretary was the person best placed to animate it.

Sir Edward’s qualifications for such responsibility were of recent coinage. Notoriously idle as a young man, he had been sent down from Oxford, but returned to get a third in jurisprudence. He entered politics as much through Whig inheritance as ambition. He spoke no foreign language and, when foreign secretary, never travelled abroad – or at least not until he had to accompany King George V to Paris in April 1914. He seemed happier as a country gentleman, enjoying his enthusiasms of fishing and ornithology. His first wife increasingly refused to come to London, remaining at Fallodon, the family seat in Northumberland. Their life together was chaste and childless, but not unaffectionate.

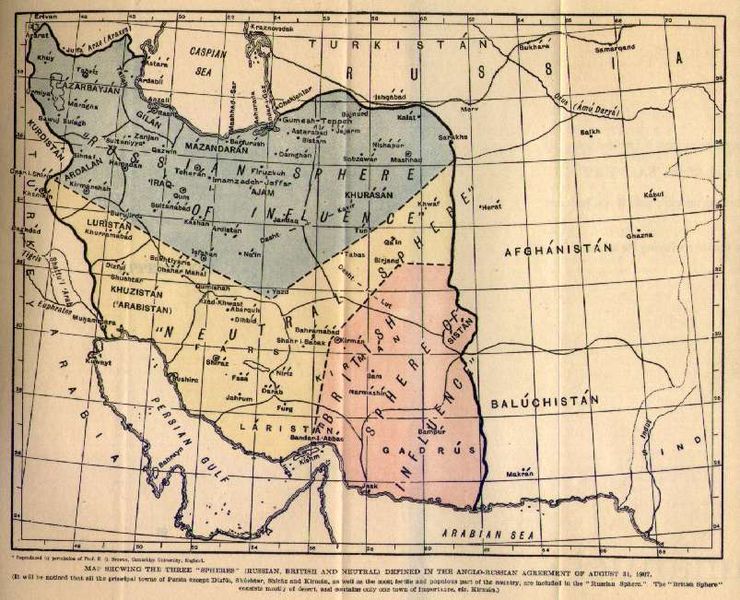

Soon after becoming Foreign Secretary, Grey was careful to assure Russian ambassador Count Alexander Benckendorff that he wanted a closer and less fraught relationship with St. Petersburg. Britain’s long-running dispute with the expanding Russian Empire in Asia stood in the way of any co-operation between the two great powers: the “Great Game” across central Asia had been in progress for nearly a century and neither side trusted the other. British concerns that any advance of Russian interests across that vast swathe of land were part of long term plans to destabilize the Indian frontier and eventually to absorb India. Whether these fears were realistic is beside the point: they had driven Raj policy in India despite the low chance of them turning into actual dangers. The disagreements were partially settled with the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907, where both Russian and British regional interests were codified:

Formally signed by Count Alexander Izvolsky, Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire, and Sir Arthur Nicolson, the British Ambassador to Russia, the British-Russian Convention of 1907 stipulated the following:

- That Persia would be split into three zones: A Russian zone in the north, a British zone in the southeast, and a neutral “buffer” zone in the remaining land.

- That Britain may not seek concessions “beyond a line starting from Qasr-e Shirin, passing through Isfahan, Yezd (Yazd), Kakhk, and ending at a point on the Persian frontier at the intersection of the Russian and Afghan frontiers.”

- That Russia must follow the reverse of guideline number two.

- That Afghanistan was a British protectorate and for Russia to cease any communication with the Emir.

A separate treaty was drawn up to resolve disputes regarding Tibet. However, these terms eventually proved problematic, as they “drew attention to a whole range of minor issues that remained unsolved”.

While the convention did not resolve every outstanding issue between the two imperial powers, it smoothed the path to further negotiations on European issues. One of the things the two had to consider was the expansion of German activity in Ottoman territory, especially the Baghdad Railway project, which threatened to extend German influence deep into the oil producing regions of Mesopotamia just as Britain was contemplating switching the Royal Navy from coal to oil. German engineers and financiers had already proven their worth to the Ottomans by building the Anatolian Railway in the 1890s, connecting Constantinople with Ankara and Konya.

Vernon Bogdanor’s recent History Today article explains Grey’s role in bringing Britain into the war alongside the French and Russians:

The growth of German power posed a challenge to an international system based on the Concert of Europe, developed at the Congress of Vienna following the defeat of Napoleon, whereby members could call a conference to resolve diplomatic issues, a system Britain, and particularly the Liberals in government in 1914, were committed to defend. Sir Edward Grey had been foreign secretary since 1905, a position he retained until 1916, the longest continuous tenure in modern times. He was a right-leaning Liberal who found himself subject to more criticism from his own backbenchers than from Conservative opponents. In his handling of foreign policy his critics alleged that Grey had abandoned the idea of the Concert of Europe and was worshipping what John Bright had called ‘the foul idol’ of the balance of power. They suggested that he was making Britain part of an alliance system, the Triple Entente, with France and Russia and that he was concealing his policies from Parliament, the public and even from Cabinet colleagues. By helping to divide Europe into two armed camps he was increasing the likelihood of war.

On his appointment in December 1905 Grey had indeed maintained the loose Anglo-French entente of 1904, which the Conservatives of the previous government had negotiated. He extended that policy by negotiating an entente with France’s ally, Russia, in 1907. In 1905 France was embroiled in a conflict with Germany over rival claims in Morocco. The French had essentially said to Lord Lansdowne, Grey’s Conservative predecessor: ‘Suppose this conflict leads to war – if you are to support us, let us consult together on naval matters to consider how your support can be made effective.’ The Conservatives had responded that, while they would discuss contingency plans, they could not make any commitments.

Grey continued the naval conversations and extended them to include military dialogue. He informed the prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, and two senior ministers of these talks, but not the rest of the Cabinet. Nevertheless, Britain could not be committed to military action without the approval of both Cabinet and Parliament. In November 1912, at the insistence of the Cabinet, there was an exchange of letters between Grey and the French ambassador, Paul Cambon, making it explicit that Britain was under no commitment, except to consult, were France to be threatened. In 1914, furthermore, the French never suggested that Britain was under any sort of obligation to support them, only that it would be the honourable course of action.

Romancing the bear, romancing the lion: France breaks out of imposed isolation

As I discussed back in part four of this series, the French had been left diplomatically isolated in Europe by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, but that began to change as Kaiser Wilhelm II took the throne and started imposing his will on German foreign policy. French money opened opportunities for French diplomacy, to the long-term benefit of French security. The Franco-Russian alliance was signed in 1894, signifying the end of French encirclement (Bismarck’s policy) and the start of German encirclement (Kaiser Wilhelm’s nightmare).

Britannia and Marianne dancing together on a 1904 French postcard: a celebration of the signing of the Entente Cordiale. (via Wikipedia)

French public opinion was still ambivalent at best about Britain — the PR and humanitarian disaster that was the Boer War had only just faded from the headlines, and there was still much resentment over the Fashoda incident — but the French government recognized the importance of gaining British support (and the British government was conscious of how low their international reputation had gone). Huw Strachan:

The previous Conservative government had in 1895 moved from “splendid isolation” to embrace the need to form alliances. But it was Sir Edward who narrowed these options by excluding the possibility of a deal with Germany. As a Liberal Imperialist, concerned by the evidence of British decline in the South African war, Sir Edward increasingly fixed Britain to France and then to Russia. The latter relationship may have looked frayed by 1914, but that with France was buttressed by military and naval talks. The result was not so much a balance of power in Europe as the isolation of Germany.

Moroccan crises and using the Kaiser as a bargaining chip

The First Moroccan Crisis of 1905-6 was a potential flashpoint between the Entente Cordiale and the German Empire. Germany was hoping to split the Entente or at least to gain territorial concessions in exchange for a resolution. Kaiser Wilhelm was on a cruise to the Mediterranean and had been intending to bypass Tangier, but the situation was manipulated by the Foreign Office in Berlin so that he eventually felt he had to put in an appearance. In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan describes the scene:

Although Bülow had repeatedly advised him to stick to polite formalities, Wilhelm got carried away in the excitement of the moment. To Kaid Maclean, the former British soldier who was the sultan’s trusted advisor, he said, “I do not acknowledge any agreement that has been come to. I come here as one Sovereign [sic] paying a visit to another perfectly independent sovereign. You can tell [the] Sultan this.” Bülow had also advised his master not to say anything at all to the French representative in Tangier, but Wilhelm was unable to resist reiterating to the Frenchman that Morocco was an independent country and that, furthermore, he expected France to recognize Germany’s legitimate interests there. “When the Minister tried to argue with me,” the Kaiser told Bülow, “I said ‘Good Morning’ and left him standing.” Wilhelm did not stay for the lavish banquet which the Moroccans had prepared for him but before he set off on his return ride to the shore, he found time to advise the sultan’s uncle that Morocco should make sure that its reforms were in accordance with the Koran. (The Kaiser, ever since his trip to the Middle East in 1898, had seen himself as the protector of all Muslims.) The Hamburg sailed on to Gibraltar, where one of its escort ships accidentally managed to ram a British cruiser.

Tension rose so high that both Germany and France were looking to their mobilization timetables (France cancelled all military leave and Germany started moving reserve units to the frontier) before the diplomats were able to agree to meet at the conference table rather than the battlefield. The Algeciras Conference lasted from January to April, 1906, and the French generally had the better of the negotiations (with support from Britain, Russia, Italy, Spain, and the United States) while the Germans found themselves supported only by the Austro-Hungarian delegation. France ended up making a few token concessions, but overall retained their position in Morocco.

The Agadir Crisis of 1911 was the second incident in Morocco, where Germany tried a little bit of literal gunboat diplomacy with the gunboat SMS Panther. The port of Agadir was closed to foreign trade, but the Panther (and later the light cruiser SMS Berlin) was sent to “protect German nationals” in southern Morocco from rebel forces. A minor problem turned out to be that there were no conveniently threatened Germans in the region. Margaret MacMillan:

The Foreign Ministry only got round to getting support for its claim that German interests and German subjects were in danger in the south of Morocco a couple of weeks before the Panther arrived off Agadir, when it asked a dozen German firms to sign a petition (which most of them did not bother to read) requesting German intervention. When the German Chancellor, Bethmann, produced this story in the Reichstag he was met with laughter. Nor were there any German nationals in Agadir itself. The local representative of the Warburg interests who was some seventy miles to the north started southwards on the evening of July 1. After a hard journey by horse along a rocky track, he arrived at Agadir on July 4 and waved his arms to no effect from the beach to attract the attention of the Panther and the Berlin. The sole representative of the Germans under threat in southern Morocco was finally spotted and picked up the next day.

France reacted to the German provocation, despite efforts by Sir Edward Grey to restrain them: eventually he recognized that “what the French contemplate doing is not wise, but we cannot under our agreement interfere”. German public opinion, on the other hand, was ecstatic:

After its setbacks earlier on in Morocco and in the race for colonies in general, with the fears of encirclement in Europe by the Entente powers, Germany was showing that it mattered. “The German dreamer awakes after sleeping for twenty years like the sleeping beauty,” said one newspaper.

[…]

In Germany, public opinion, which had been largely indifferent to colonies ten years earlier, now was seized with their importance. The German government, which was already under considerable pressure from those German businesses with interests in Morocco, felt that it had much to gain by taking a firm stand. […] The temptation for Germany’s new Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Holweg, and his colleagues to have a good international crisis to bring all Germans together in support of their government was considerable.

Eventually, after negotiations, France and Germany signed the Treaty of Fez, which granted France Germany’s recognition of her rights in Morocco in exchange for ceded French territory in French Equatorial Africa (which was annexed to the existing German colony in Togoland), including direct access to the Congo River. In addition, Spain was granted rights to a portion of northern Morocco which became Spanish Morocco.

Not part of the treaty terms, but of rather greater significance in the near future, France and Britain agreed to share responsibility for the naval defence of France: the Royal Navy took on the responsibility for defending the north coast of France, while the French navy redeployed almost all ships to the western Mediterranean with the explicit agreement to defend British interests in the region.

I’m finding each successive part of this blog series to be taking longer to put together, and not from a lack of material! I’m hoping to have the next installment posted sometime this weekend or early next week.