Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-4/1447/3).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

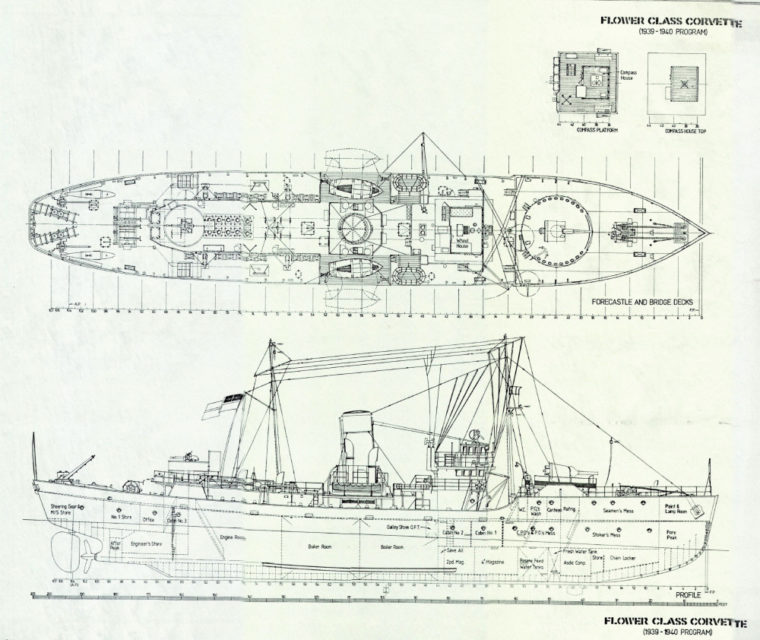

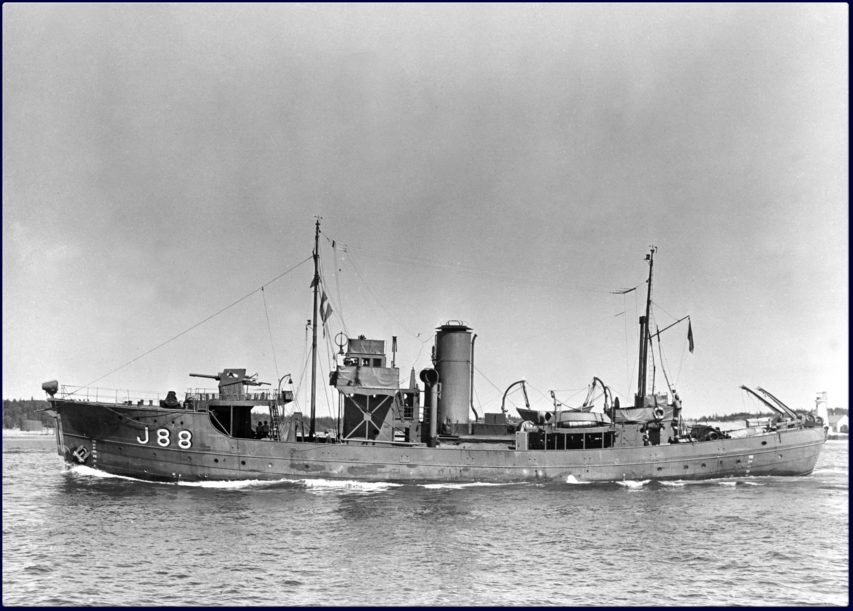

Returning to the corvettes themselves for a moment, while I have already spoken of the diversity of the modifications that they would receive [in Part 7], it is important to discuss the modifications that Canadians gave to their own corvettes in comparison to those made to Royal Navy ships. The RN used its corvettes for ocean escort and had begun to implement some of the modification to individual ships of the class to make the vessels more suitable for work on the open sea. The lengthened forecastle increased available crew space (required as ships’ crews were augmented with extra ratings for the newer equipment being fitted) and helped to make the ships’ interior spaces significantly drier. The bows were also strengthened to take the pounding of the heavy seas typically encountered in the North Atlantic. The first Canadian-built corvettes could have been delayed in order to incorporate these changes while still in the builders’ hands, but the shortage of ships meant that they went ahead largely as originally planned. The major Canadian alteration of the original design reflected the corvettes’ intended coastal operational role: minesweeping gear. The alterations to the original design, involving modification of the quarter-deck, cutting back the engine-room casing to accommodate a steam winch, broadening the stern to fit both the minesweeping wires and the depth charge rails, and the extra storage for the minesweeping gear when not in use, had already delayed the delivery of the ships to the navy.

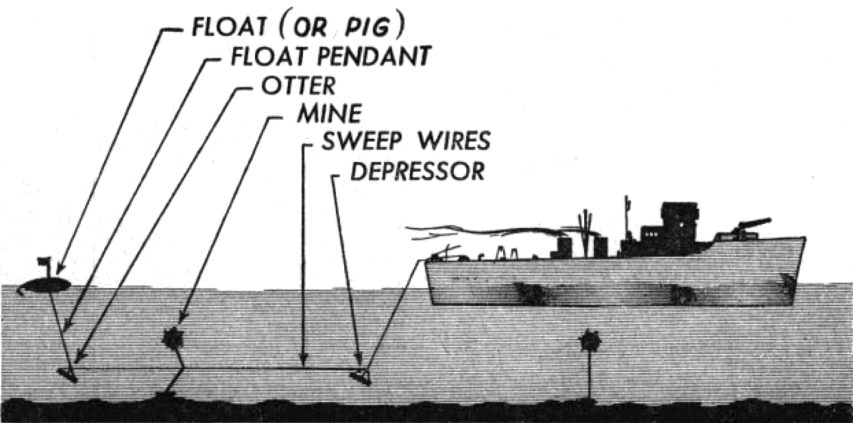

[Editor’s Note: Minesweeping, while not the primary intended role for the Flower-class corvettes (especially without gyrocompasses!), was a viable alternate task. Here’s a post-war diagram of how WW2 minesweeping was done (from History on the Net‘s Minesweepers of WW2 page)]:

[Minesweeper-equipped ships would] “sweep” anchored mines by cutting their mooring ropes or chains, permitting the mines to float to the surface where they could be destroyed by gunfire.

Magnetically activated “influence” mines were defeated with a strong electrical current passed through a loop of cable, neutralizing the detonator. Acoustic mines, which responded to the noise of a ship’s engines and propellers, were prematurely detonated by underwater noisemakers operating on suitable harmonic frequencies.

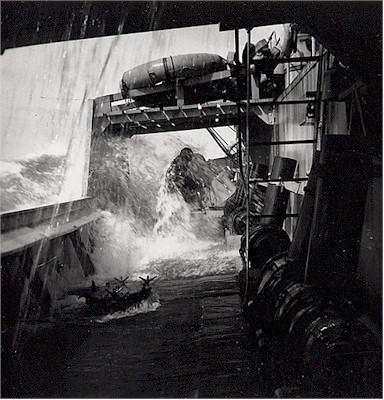

RCN personnel preparing to launch a minesweeping float from HMCS Alberni off the coast of British Columbia, March 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-179942

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

All of this delayed completion and may have hardened the Staff to any further delays occasioned by major alterations. Moreover, that the Naval Staff was not unduly concerned about the A/S performance of the corvettes is evidenced by the fact that the addition of a full minesweeping kit “had an adverse effect on the operations of the A/S gear”. The latter, as the Staff went on to observe, was carried forward and was affected by the corvette’s tendency to trim by the stern when fitted for minesweeping. In practice, however, the original corvette design, when fully stored and armed, tended to trim by the bows, which also affected A/S efficiency. The addition of extra weight in the stern may unwittingly have compensated for the design fault.

More important in terms of sea-keeping and habitability in deep-sea operations was the extension of the foc’sle. News of this major alteration reached NSHQ while most of the vessels of the first program were still in the builders’ hands. Although the RCN would make allowances for more crewmen, better refrigeration, a more powerful wireless set, and more depth charges — all indications that corvettes were expected to go farther afield and stay longer — the navy did not act on this fundamental alteration in basic structure of its first sixty corvettes. However, the Staff did recognize the value of the design improvements. … In the meantime, the RCN plodded along with escorts which, as late as the end of 1940, the navy still considered inshore auxiliaries. In any event, corvettes were still tied closely to the defended-port system under the terms of Plan Black. It is also arguable that the Staff’s failure to extend the foc’sles of corvettes when it had the chance stemmed from the navy’s need of ships to permit expansion really to begin, or from the increasing gravity of the war at sea. Whatever the case, it was a lost opportunity that would come to haunt the navy.

The forecastle extension (or lack thereof) would come to be the norm for the RCN and NSHQ: certain trivial modifications seemingly at random, major ones delayed exponentially. The after gun platform (for the Pom-Pom) was moved further to the rear of the ship so that it was not in danger of blowing away the mainmast, and would remain further to the rear long after the secondary mast was discarded. Shortage of primary AA armament saw a number of .5-inch Colt and Browning machine guns acquired from the U.S. and fitted in twin mounts (two in the aft gun position and one twin-mount on either side of the bridge). Inability to acquire sufficient Colt or Browning machine guns meant the return of the Lewis guns.

Other differences between RN and RCN corvettes were much less noticeable, but had a more important effect on the performance of the ships as deep-sea escorts. There was, for example, no provision in Canadian plans for a breakwater on the foc’sle of original corvettes. Without it, water shipped forward was able to run aft and pour into the open welldeck — the crew’s main thoroughfare. The British soon corrected this, but the RCN moved with incredible slowness on this simple matter, and as a result Canadian corvettes were unnecessarily wet. Canadian corvettes were also completed without wooden planking or some form of synthetic deck covering to prevent slipping in the waist of the ship, where the depth-charge throwers were fitted. Since this area was also constantly wet, the difficulties of loading charges can be imagined.

The most telling shortcoming of Canadian corvettes, and the one that was to cause the most difficulty in the struggle for efficiency, was the lack of gyro-compasses. The latter were at a premium in Canada, so the Naval Staff decided to fit them to the Bangor minesweepers, whose need for accurate navigation was paramount. The first Canadian-built corvettes (including those built to Admiralty accounts) were equipped with a single magnetic compass and the most basic of ASDIC, the type 123A. Even by 1939 standards the 123A was obsolete and in the RN was considered only suited to trawlers and lesser vessels. The 123A’s standard compass, graduated in “points” and not in degrees, made it equally hard for captains to co-ordinate operations between two ships or to undertake accurate submarine hunts and depth-charge attacks. The single binnacle and its attendant trace recorder were mounted in a small hut, above the wheelhouse. During an action it was impossible for a captain to be both in the ASDIC hut and outside on the bridge wings, the only place from which he could obtain an overall perspective on the situation. Nor was the needle of the standard compass properly stabilized, a deficiency particularly noteworthy in such lively ships as corvettes. … As a final point, it should be noted that compasses were also susceptible to malfunction from the shock of firing the main armament, exploding depth charges, or simply from the pounding of the ship at sea. The tendency of Canadians to launch inaccurate depth charge attacks proved a source of continuous criticism from British officers.

Officers on the bridge of Canadian Flower class corvette HMCS Trillium, circa 1940-42.

Image from the Canadian Navy Heritage website, Image Negative Number JT-159, via Wikimedia Commons.

Partly because of a disparity of resources, partly because there was still a lot of ambiguity concerning the role that the corvettes (and the RCN) would play in the war in general, the RN corvettes outclassed RCN corvettes when it came to performance at sea. Misapplication of Staff energies also played a role.

Instead of laying down a basic policy for the engineer-in-chief to follow, the Staff haggled over every conceivable alteration to their corvettes. They insisted, for example, that inclining tests be done before .5-inch machine guns were authorized for the bridge wings, even though they knew full well that this practice had already been adopted for comparable British ships. In the final analysis it would have been much better had the RCN continued its initial practice of calling its own corvettes “Town class”, after its policy of naming them for small Canadian communities. Instead the practice was abandoned in deference to the Admiralty’s choice of “Town class” for the ex-American destroyers, and the RCN applied the British class name of “Flower” to its corvettes. Had the RCN stuck to its distinctive class name, the tremendous differences which were to prove so very important by 1942-43, might have been as apparent as they were real.

Deck awash on HMCS Trillium, circa 1943

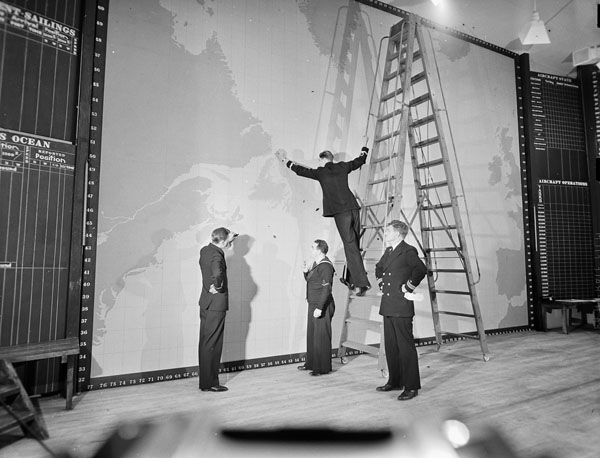

National Archives of Canada PA-037474, via HMCS Trillium page of the For Posterity’s Sake website – http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_TRILLIUM_K172.htmNSHQ’s notion that the RCN was to provide convoy escorts for the Newfoundland focal area suggests that the Naval Staff had not made the mental leap from the concept of locally based “strike forces” to the idea of a regional escort force. In this they were not alone. The distinction between two types of operation — one searching for submarines where shipping was plentiful, the other actually protecting the ships towards wich the submarines were drawn — was never very clear in the early days. NEF was, none the less, admirably suited to RCN capabilities. It also met two other vitally important criteria: it supported the government’s geopolitical aspirations and was at the same time fundamental to the war effort.

The war was entering what Churchill called “one of the great climacterics”. On June 22nd, Hitler would invade Russia and soon had her reeling. A Soviet collapse would give Hitler access to enormous resources. Even if Russia could fight them to a stalemate, there could be no Allied victory without an attack supplied by sea and mounted from the British Isles. Whether for the ultimate defence against a stronger Germany or for our own seaborne assault, Allied resources had to be turned into munitions of war and stockpiled in the UK. The resources were more than sufficient, but between the promise of the future and the need of the present lay a perilous gap of space and time that could only be bridged by ships, all the ships now available and hundreds more. Many convoys arrived at British ports each week and the tonnage unloaded was enormous. Yet a great percentage of it was what the island required simply to exist. Only the margin above that daily necessity represented the power to wage war. Munitions, aircraft, guns, tanks, and above all, aviation gasoline and fuel oil. If oil stocks fell below the point of safety, the operation of ships and planes would have to be curtailed. If U-boat attacks could not be met effectively, more ships would be lost, creating further shortages which would again reduce operations. The increasing demands of the war had to be met by a corresponding increase in the flow of cargo.

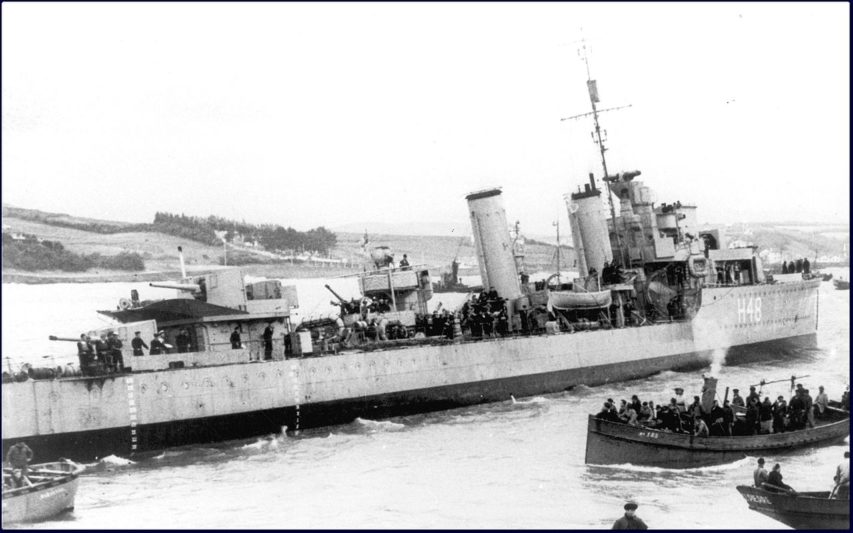

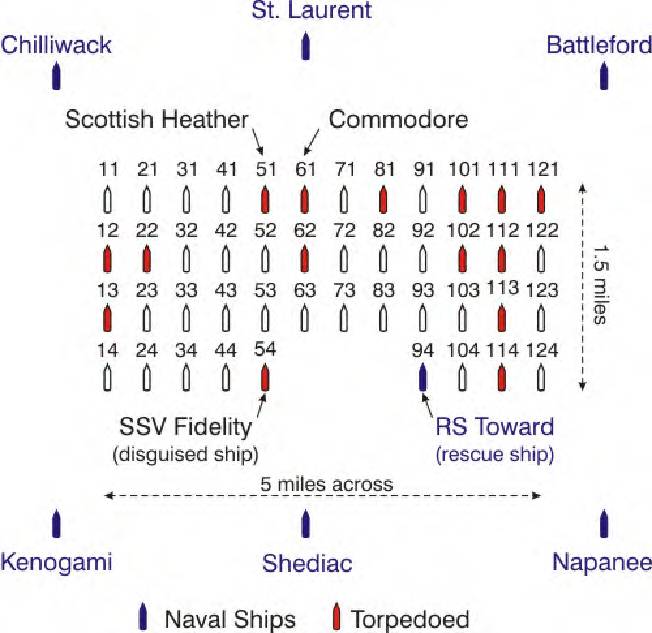

The U-boats imposed a steady drain: three merchant ships were going down for every one replaced. Eight submarines were coming into operation for every one sunk. U-boats swarmed in the Mediterranean. They were off Gibraltar, off the Cape Verde Islands at the bulge of Africa, off Cape Town far to the south. By the virtue of St John’s position alone, it bridged nearly a quarter of the gap between the Canadian seaboard and Iceland. June 1941 would also see Canada’s Commodore Murray return from Britain to become Commodore Commanding Newfoundland Escort Force. From Liverpool, the RN’s Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, Admiral Sir Percy Noble, directed the whole Atlantic battle, but Commodore Murray exercised autonomy within his own war zone. The Newfoundland Escort Force was made up of six Canadian destroyers and seventeen corvettes, plus seven destroyers, three sloops and five corvettes of the RN. Soon more ships, French, Norwegian, Polish, Belgian and Dutch, were allotted to Commodore Murray. His authority extended to all local escorts operating from St. John’s and to convoys and their escorts while in Newfoundland waters.

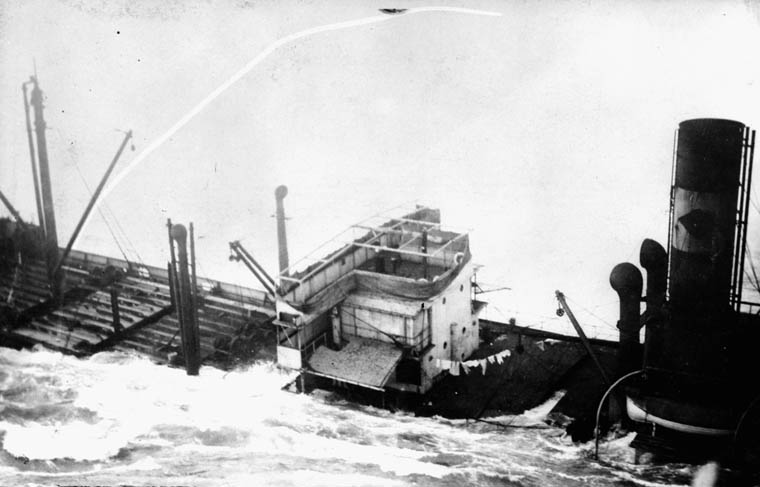

SS Rose Castle sinking and decks awash, 2 November, 1942. The original description for this item gives the date October 1942 as the date of the sinking, but according to eyewitness and survivor Gordon Hardy, the Rose Castle sank at 3:30 AM, November 2, 1942. On Oct 20, 1942, the Rose Castle was hit by a dud torpedo but was not damaged.

Library and Archives Canada/PA-192788