I’ve been quietly fascinated by the ancient Silk Road trading route spanning from the Middle East to China since I first heard about it as a kid. (The most recent book I read on the topic, Foreign Devils on the Silk Road, blended bits of the history of the route with the activities of European spies in the area preceding the start of the First World War.) At Ars Technica, Annalee Newitz summarizes some recent work in Nature that pushes back the origins of the Silk Road more than two millennia:

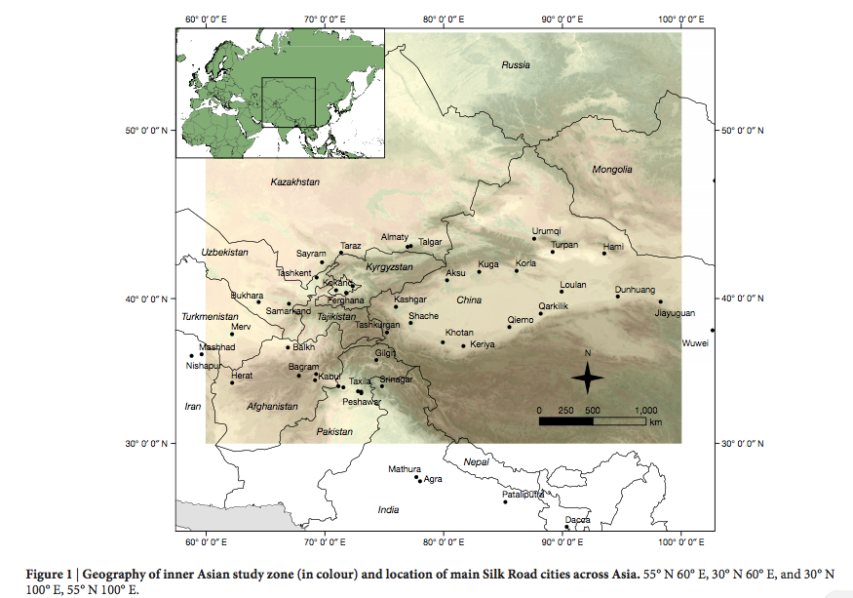

The Silk Road was a series of ancient trading routes that spanned Asia, reaching as far as the Middle East and Europe. Self-organizing and vast, it fell under the control of various empires — but never for long. The polyglot civilizations of traders who lived along its routes are the subject of legends, and more recently the Silk Road lent its name to an infamous darknet market. Historians usually date the Silk Road from roughly the 200s to the 1400s. But a new study in Nature suggests the trade routes may be 2,500 years older than previously believed and its origins much humbler than the rich cities it spawned.

Historical accounts of the Silk Road begin in China in the 100s, when the Han Dynasty used its many routes to trade with the peoples of Central and South Asia. Han soldiers protected the roads and maintained regular outposts on them, allowing wealth and knowledge to flow across the continent. Monks wandering the Silk Road brought Buddhism from India to China, while merchants brought spices, gems, textiles, books, horses, and other valuables from one part of the continent to the other. Great Silk Road cities such as Chang’an (today called Xi’an) and Samarkand grew fat on wealth from the routes that passed outside their walls.

But Washington University in St. Louis anthropologist Michael Frachetti and his colleagues wondered how people traversed the many difficult stretches of the Silk Road that switchbacked through the mountains of Central Asia. Even though these routes weren’t urban or under the protection of soldiers, people used them all the time to pass between Asia and the Middle East. We can see where these travelers camped at over 600 archaeological sites in the mountains. Writing in Nature, Frachetti and his colleagues describe how they had to devise a new approach to track the routes people took between these camps.

The problem was that previous scholars assumed people took routes that resembled what a “least cost” algorithm would draw — essentially the easiest path. This is “largely effective in lowland zones where economic networks and mobility between urban centers are consistent with ease of travel,” the researchers write in their paper. But those algorithms won’t work in the mountains, on uneven terrain that was often barren.

NHK and CCTV did a 12-part documentary on the Silk Road, with beautiful theme music by Kitaro:

Published on 18 Sep 2013

Camels plodding across the desert, and a sense of timelessness evoked by Kitaro’s theme music… NHK devoted 17 years to the planning, shooting and production of The Silk Road, which unearthed trade routes linking long-lost civilizations of East and West. A landmark in broadcasting history, this series told the story of the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

The NHK Tokushu and China’s CCTV documentary series The Silk Road began on April 7, 1980. The program started with the memorable scene of a camel caravan crossing the desert against the setting sun, with Kitaro’s music and a sense of timelessness. It was the start of an epic televisual poem.The first journey described in the series began in Chang’an (now Xi’an), at the eastern end of the ancient route. On 450,000 feet of film, the NHK crew recorded the path westward to the Pamir Heights at the Pakistan border and this material was edited to make 12 monthly broadcasts. In response to viewers’ requests that the series be extended to cover the Silk Road all the way to Rome, sequels were made over the next 10 years. Seventeen years after the program was conceived, the project was completed.

1) The Glories of Ancient Chang-An

Chang-An – China’s old center. The journey begins from Chang-An, current Xi-an that was more than 1,000 years a capital in China, and the melting pot of international influences.