Fortissax, in response to a question about the historical situation of Quebec within Canada, outlines the history from before the Seven Years’ War (aka the “French and Indian War” to Americans) through the American Revolution, the 1837-38 rebellions, the Durham Report, and Confederation:

First and foremost, Canada itself, as a state — an administrative body, if you will — was originally founded by France. Jacques Cartier named the region in 1535, and Samuel de Champlain established the first permanent French settlement in North America in Quebec City in 1608. This settlement would become the largest and most populous administrative hub for the entire territory. Canada was a colony within the broader territory of New France, which stretched from as far north as Tadoussac all the way down to Louisiana. It included multiple hereditary land-owning noblemen of Norman extraction.

During the Seven Years’ War, on 8 September 1760, General Lévis and Pierre de Vaudreuil surrendered the colony of Canada to the British after the capitulation of Montreal. Though the British had effectively won the war, the Conquest’s details still had to be negotiated between Great Britain and France. In the interim, the region was placed under a military regime. As per the Old World’s “rules of war”, Britain assured the 60,000 to 70,000 French inhabitants freedom from deportation and confiscation of property, freedom of religion, the right to migrate to France, and equal treatment in the fur trade. These assurances were formalized in the 55 Articles of the Capitulation of Montreal, which granted most of the French demands, including the rights to practice Roman Catholicism, protections for Seigneurs and clergymen, and amnesty for soldiers. Indigenous allies of the French were also assured that their rights and privileges would be respected.

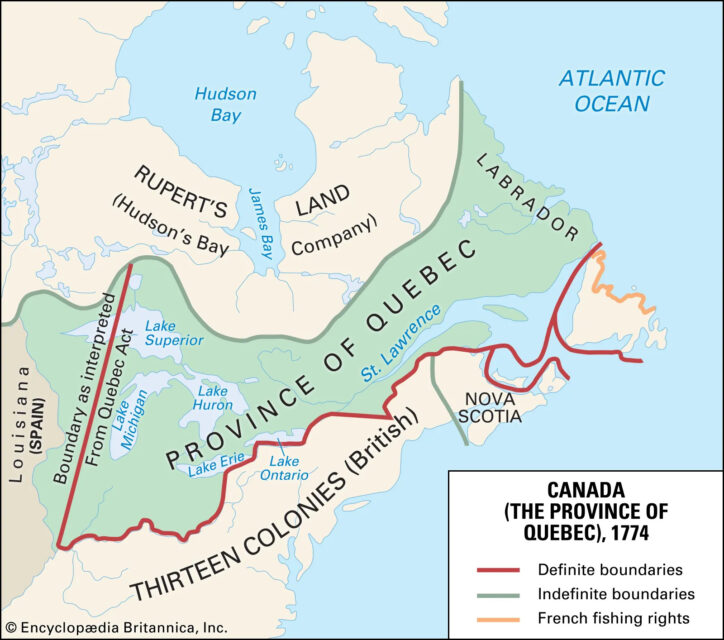

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 officially ended the war and renamed the French colony of “Canada” as “the Province of Quebec”. Initially, its borders included parts of present-day Ontario and Michigan. To address growing tensions between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies and to maintain peace in Quebec, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act in 1774. This act solidified the French-speaking Catholic population’s rights, such as the free practice of Catholicism, restoration of French civil law, and exemption from oaths referencing Protestant Christianity. These provisions satisfied the Québécois Seigneurs (land-owning nobleman), and clergy by preserving their traditional rights and influence. However, some Anglo settlers in America resented the Act, viewing it as favoring the French Catholic majority. Despite this, the Act helped maintain stability in Quebec, ensuring it remained loyal to Britain during the American Revolutionary War and Quebec was fiercely opposed to liberal French revolutionaries.

British concessions, from the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris to the Quebec Act of 1774, safeguarded the cultural and religious identity of Quebec’s French-speaking Catholic population, fostering their loyalty during a period of significant upheaval in North America. Following this period, merchant families such as the Molsons began establishing themselves in Montreal, alongside early Loyalist settlers who trickled into areas now known as the Eastern Townships. These merchant families quickly ingratiated themselves with the local Norman lords and seigneurs.

The Lower Canada Rebellion arose in 1837-1838 due to the Château Clique oligarchy (an alliance of Anglo-Scottish industrialists and French noble landowners), in Quebec refusing to grant legislative power to the French Canadian majority. The rebellion was not solely a French Canadian effort; to the chagrin of both chauvinistic Anglo-Canadians and French Canadians, who in recent years believed it was either a brutal crackdown on French degeneracy, or a heroic class struggle of French peasants against an oppressive Anglo elite. It included figures like Wolfred Nelson, an Anglo-Quebecer who personally led troops into battle.

In response to the unrest following the rebellions of 1837-1838, Lord Durham, a British noble, was sent to Canada to investigate and propose solutions. His controversial recommendation, outlined in the Durham Report of 1839, was to abolish the separate legislatures of Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec) and merge them into a single entity: the Province of Canada. This unification aimed to demographically and culturally assimilate the French Canadian population by creating an English-speaking majority.

However, the strategy failed for multiple reasons, and was given up shortly after. Lord Durham, having neither been born nor raised in the New World, underestimated the complexities of Canadian society, which was a unique fusion of Old World ideas in a New World setting. His assumption that French Canadians could be assimilated ignored their strong cultural identity, rooted in large families, which encouraged high birth rates as a means of survival. While Durham hoped unification would erode divisions, the old grievances between the British and French began to dissipate naturally.

Despite Lord Durham’s intentions, French Canadians maintained their dominance in Quebec. Families averaged five children per household for over 230 years, a trend actively encouraged by the Catholic Church’s policy of La Revanche des Berceaux (the Revenge of the Cradles). This strategy aimed to preserve French Canadian culture and identity amidst the British short-lived attempts at assimilation. In Montreal, British industrialists expanded their influence by forging alliances with French landowning nobles through business partnerships and intermarriage. This blending of elites produced a bilingual Anglo-French upper class that became historically influential.

Such alliances drew on long-standing connections established as early as 1763 and later exemplified by the North West Company (NWC). The NWC in particular is interesting as a prominent fur trading enterprise of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in that it embodied this fusion of cultures. Led primarily by Anglo-Scots, the company’s leaders frequently formed unions or marriages with French Canadian women, fostering vital ties with the French Canadian communities crucial to their trade. Simon McTavish, known as the “father” of the NWC, maintained alliances with French Canadian families, while his nephew, William McGillivray, and other leaders like Duncan McGillivray followed similar paths. Explorers such as Alexander MacKenzie and David Thompson married French women. These unions strengthened familial and cultural bonds, shaping the broader Anglo-French collaboration that defined this period.

This relative harmony between Anglo and French Canadians continued with the formation of the modern Canadian state in 1867 during Confederation. Sir John A. Macdonald deliberately chose George-Étienne Cartier as his second-in-command. This collaboration contributed to the emergence of Canada’s ethnically Anglo-French elite, who have historically been bilingual. This legacy is evident in the backgrounds of many Canadian politicians, such as the Trudeaus, Mulroneys, Martins, Cartiers, and countless others who have both Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian roots.

In more recent history, this dynamic has been further solidified by the federal government, where higher-paid positions often require bilingual proficiency. Interestingly, about 20% of Canada’s population is bilingual, reflecting the ongoing influence of this historical coexistence.

The last cannon which is shot on this continent in defence of Great Britain will be fired by the hand of a French Canadian.

~ George Etienne Cartier