The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 8 Nov 2024In March 1950, Stalin finally approves Kim Il-sung’s plans for an invasion of South Korea. But why now? Today Indy looks at the wider Cold War context that fed into Stalin and Mao Zedong’s decision making. He also examines whether the lack of a clear and public commitment from the US to defend the Asian theatre helped to invite the invasion.

(more…)

November 9, 2024

Did US Indecision Encourage Stalin in Korea?

Bill C-413 “is aimed at preventing her fellow Canadians from saying anything positive about Indian residential schools”

Nina Green suggests that Bill C-413’s sponsor might be the first person in Canada to face criminal charges in that piece of legislation if her private member’s bill gets Royal Assent:

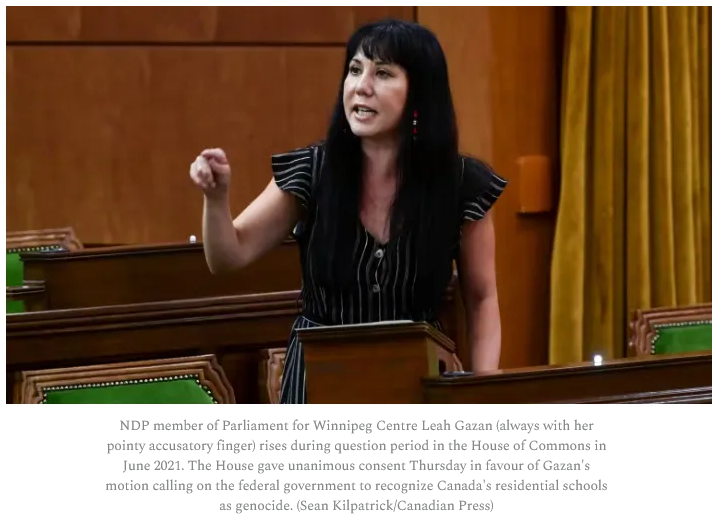

On 31 October 2024 Member of Parliament Leah Gazan called a press conference to lobby for Bill C-413, her private member’s bill designed to criminalize her fellow citizens for disagreeing with her views.

Gazan led off the press conference with this statement:

Good morning, everybody. I’m Leah Gazan, and I’m the Member of Parliament from Winnipeg Centre, and we’re here to discuss support of Bill C-413 to amend the Criminal Code to include the willful promotion of hate against Indigenous peoples by condoning, downplaying, justifying the residential schools.

To evoke an emotional response, Gazan used the word “violence” a dozen times during her press conference, falsely equating speech with violence, although violence by definition involves physical force.

Gazan’s bill is obviously not aimed at preventing physical violence against Indigenous people. It is aimed at preventing her fellow Canadians from saying anything positive about Indian residential schools.

Earlier, on 27 September 2024, Gazan made the bill personal, telling CTV News that “my family has been impacted by residential school”, implying that she had been motivated to introduce her bill because of the serious harm residential schools had inflicted on her own family.

In fact, the exact opposite is true. Residential schools had a positive effect on Leah Gazan’s family.

On her father’s side, Gazan is Jewish, and her maternal grandfather was Chinese. Thus her only possible connection to Indian residential schools is through her maternal grandmother, Adeline LeCaine, the daughter of Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890-1964).

What we learn about John LeCaine turns out to be surprising. He was the son of a white North West Mounted Police officer, William Edward Archibald LeCain (1859-1915), and Emma Loves War, whose Lakota Sioux family sought refuge in Canada with Chief Sitting Bull and 5000 of his people after the massacre of Custer and his men at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. […]

Since he had a white father and an American Indian mother, John LeCaine was, in the terminology of the day, a half-breed, and ineligible to attend a residential school since federally-funded Indian residential schools were reserved for status Indians under the Indian Act. However an exception was made, and both John LeCaine and his sister Alice LeCaine (1888-1976) were admitted to the Regina Industrial School. John LeCaine attended for seven years, from 1899 to 1906 when he was 9 to 16 years of age. While there he learned to read and write English proficiently, and mastered agricultural and carpentry skills which equipped him to apply, like white settlers at the time, for a homestead, which he proved up in 1913. In 1914 he wrote to the Department of the Interior asking for a ruling on whether his two half-brothers — who were full-blooded Sioux — could also apply for homesteads.

The proficiency in English he acquired at the Regina Industrial School enabled John LeCaine to became a writer and a historian of the Lakota people. In later years he mapped the places he and his stepfather, Okute Sica, had visited on a journey to the Frenchman River in 1910, and wrote a collection of stories told to him by Sioux Elders, Reflections of the Sioux World, as well as other articles, including some published in the Oblate journal, The Indian Record.

History of SAW (Squad Automatic Weapon) use in the US Army

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jul 26, 2024The first squad automatic weapon used by the US Army was the French Mle 1915 Chauchat, which was the primary LMG or automatic rifle for troops in the American Expeditionary Force in World War One. At that time, the Chauchat was a company-level weapon assigned where the company commander thought best. In World War Two, the Chauchat had been replaced by the BAR, and one BAR gunner was in each 12-man rifle platoon. The BAR was treated like a heavy rifle though, and not like a support weapon as light machine guns were in most other armies.

After Korea the value of the BAR was given more consideration and two were put in each squad instead of one, but the M14 replaced the BAR before it could gain any greater doctrinal importance. The M14 was intended to basically go back to the World War Two notion of every man equipped with a very capable individual weapon, and the squad having excellent flexibility and mobility by not being burdened with a supporting machine gun. The M60 machine guns were once again treated as higher-level weapons, to be attached to rifle squads as needed.

After Vietnam, experiments with different unit organization — and with the Stoner 63 machine guns — led to the decision that a machine gun needed to be incorporated into the rifle squad. This led to the request for what became the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon, and its adoption in the 1980s. At last, the American rifle squad included an organic supporting machine gun.

Today, the USMC is once again going back to the earlier model with every rifleman carrying the same weapon, now an M27 Individual Automatic Rifle. The Army may also change its organizational structure with the new XM7 and XM250 rifle and machine gun, but only time will tell …

(more…)

QotD: George Bernard Shaw

… Shaw is not at all the heretic his fascinated victims see him, but an orthodox Scotch Presbyterian of the most cock-sure and bilious sort. In the theory that he is Irish I take little stock. His very name is as Scotch as haggis, and the part of Ireland from which he comes is peopled almost entirely by Scots. The true Irishman is a romantic; he senses religion as a mystery, a thing of wonder, an experience of ineffable beauty; his interest centers, not in the commandments, but in the sacraments. The Scot, on the contrary, is almost devoid of that sort of religious feeling; he hasn’t imagination enough for it; all he can see in the Word of God is a sort of police regulation; his concern is not with beauty but with morals. Here Shaw runs true to type. Read his critical writings from end to end, and you will not find the slightest hint that objects of art were passing before him as he wrote. He founded, in England, the superstition that Ibsen was no more than a tin-pot evangelist — a sort of brother to General Booth, Mrs. Pankhurst, Mother Eddy and Billy Sunday. He turned Shakespeare into a prophet of evil, croaking dismally in a rain-barrel. He even injected a moral content (by dint of abominable straining) into the music dramas of Richard Wagner, surely the most colossal slaughters of all moral ideas on the altar of beauty ever seen by man. Always this ethical obsession, the hall-mark of the Scotch Puritan, is visible in him. He is forever discovering an atrocity in what has hitherto passed as no more than a human weakness; he is forever inventing new sins, and demanding their punishment; he always sees his opponent, not only as wrong, but also as a scoundrel. I have called him a good Presbyterian.

H.L. Mencken, “Shaw as Platitudinarian”, The Smart Set, 1916-08.