One particular feature of Rome’s system of magistrates is that the offices were organized from a relatively early point into a “career path” called the cursus honorum or “path of honors”. Now we have to be careful here on a few points. First, our sources tend to retroject the cursus honorum back to the origins of the republic in 509, but it’s fairly clear in those early years that the Romans are still working out the structure of their government. For instance our sources are happy to call Rome’s first magistrates in the early years “consuls“, but in fact we know1 that the first chief magistrates were in fact praetors. Then there is a break in the mid-400s where the chief executive is vested briefly in a board of ten patricians, the decemviri. This goes poorly and so there is a return to consuls, soon intermixed from 444 with years in which tribuni militares consulari potestate, “military tribunes with consular powers”, were elected instead (the last of these show up in 367 BC, after which the consular sequence becomes regular). Charting those changes is difficult at best because our own sources, writing much later, are at best modestly confused by all of this. I don’t want to get dragged off topic into charting those changes, so I’ll just once again commend the Partial Historians podcast which marches through the sources for this year-by-year. The point here is that this system emerges over time, so we shouldn’t project it too far back, though by 367 or so it seems to be mostly in place.

One particular feature of Rome’s system of magistrates is that the offices were organized from a relatively early point into a “career path” called the cursus honorum or “path of honors”. Now we have to be careful here on a few points. First, our sources tend to retroject the cursus honorum back to the origins of the republic in 509, but it’s fairly clear in those early years that the Romans are still working out the structure of their government. For instance our sources are happy to call Rome’s first magistrates in the early years “consuls“, but in fact we know1 that the first chief magistrates were in fact praetors. Then there is a break in the mid-400s where the chief executive is vested briefly in a board of ten patricians, the decemviri. This goes poorly and so there is a return to consuls, soon intermixed from 444 with years in which tribuni militares consulari potestate, “military tribunes with consular powers”, were elected instead (the last of these show up in 367 BC, after which the consular sequence becomes regular). Charting those changes is difficult at best because our own sources, writing much later, are at best modestly confused by all of this. I don’t want to get dragged off topic into charting those changes, so I’ll just once again commend the Partial Historians podcast which marches through the sources for this year-by-year. The point here is that this system emerges over time, so we shouldn’t project it too far back, though by 367 or so it seems to be mostly in place.

The second caution is that the cursus honorum was, for most of its history, a customary thing, a part of the mos maiorum, rather than a matter of law. But of course the Romans, especially the Roman aristocracy, take both the formal and informal rules of this “game” very seriously. While unusual or spectacular figures could occasionally bend the rules, for most of the third and second century, political careers followed the rough outlines of the cursus honorum, with occasional efforts to codify parts of the process in law during the second century, beginning with the Lex Villia in 180 BC, but we ought to understand that law and others of the sort as mostly attempting to codify and spell out what were traditional practices, like the generally understood minimum ages for the offices, or the interval between holding the same office twice.

That said, there is a very recognizable pattern that was in some cases written into law and in other cases merely customary (but remember that Roman culture is one where “merely customary” carries a lot of force). Now the cursus formally begins with the first major office, the quaestorship, but there are quite a few things that an aspiring Roman elite needs to do first. The legal requirement is that our fellow – and it must be a fellow, as Roman women cannot hold office (or vote) – needs to have completed ten years of military service (Polyb. 6.19.1-3). But there are better and worse ways to discharge this requirement. The best way is being appointed as junior officers, military tribunes, in the legions. We’ll talk about this office in a bit, but during this period it served both as a good first stepping stone into political prominence as well as something more established Roman politicians did between major office-holding, perhaps as a way of remaining prominent or to curry favor with the more senior politicians they served under or simply because military exigency meant that more experienced hands were wanted to lead the army.

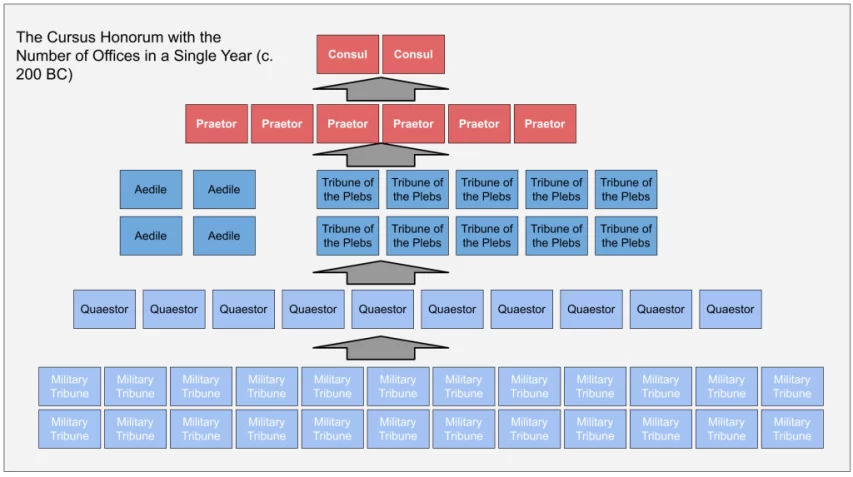

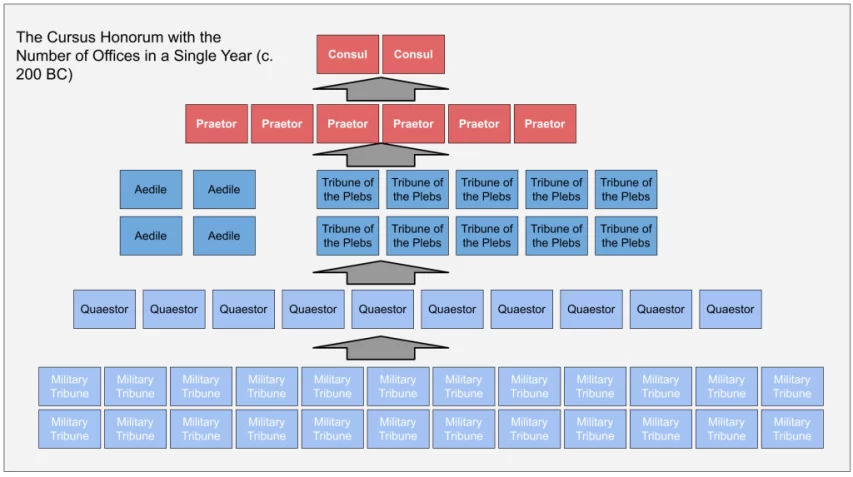

A diagram of the elected offices of the cursus honorum. Note that there were additional appointed military tribunes.

There are a bunch of other minor magistrates that are effectively “pre-cursus” offices too, but we don’t know a lot about them and they don’t seem generally to show up as often in the careers of the sort of Romans making their way up to the consulship, though this may be simply because our sources don’t mention them as much at all and so we simply don’t know who was holding them in basically any year. We’ll talk about them at the end of this set of posts, because they are important (particularly for non-elites).

I should note at the outset: all of these offices are elected annually unless otherwise noted, with a term of service of one year. You never hold the same office twice until you reach the consulship, at which point you can seek re-election, after a respectable delay (which is later codified into law and then ignored), but you may serve as a military tribune several times (this was normal, in fact, as far as we can tell).

The first major office of the cursus was the quaestorship. The number of quaestors elected grows over time. Initially just two, their number is increased to four in 421 (two assigned to Rome, one to each of the consuls) and then to six in the 260s (initially handling the fleet, then later to assist Roman praetors or pro-magistrates in the provinces) and then eight in 227. There may have been two more added to make ten somewhere in the Middle Republic, but recent scholarship has cast doubt on this, so the number may have remained eight until being expanded to twenty under Sulla in 81 BC through the aptly named lex Cornelia de XX quaestoribus (the Cornelian Law on Twenty Quaestors, Sulla being Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix).2 It’s not clear if there was a legal minimum age for the quaestors and we only know the ages of a few (25, 27, 29 and 30, for the curious) so all we can say is that officeholders tended to hold the office in their twenties, right after finishing their mandatory stint of military service.3 Serving as a quaestor enables entrance into the Senate, though one has to wait for the next census to be added to the Senate rolls by the censors.

After the quaestorship, aspirants for higher office had a few options. One option was the office of aedile; there were after 367 four of these fellows. Two were plebeian aediles and were not open to patricians, while the two more prestigious spots were the “curule” aediles, open to both patricians and plebeians. The other option at this stage for plebeian political hopefuls was to seek election as a tribune of the plebs, of which there were ten annually, we’ll talk about these fellows in a later post because they have wide-ranging, spectacular and quite particular powers.

After this was the praetorship, the first office which came with imperium. Initially there may have just been one praetor; by the 240s there are two (what will become the praetor urbanus and the praetor peregrinus). In 227 the number increases to four, with the two new praetors created to handle administration in Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. That number then increases to six in 198/7, with the added praetors generally being sent to Spain. Finally Sulla raises the number to eight in 81 BC. The minimum age seems to have been 39 for this office.

Finally comes the consulship, the chief magistrate of the Roman Republic, who also carried imperium but of a superior sort to the praetors. There were always two consuls and their number was never augmented. For our period (pre-Sulla) the consuls led Rome’s primary field armies and were also the movers of major legislation. Achieving the consulship was the goal of every Roman embarking on a political career. This is the only office that gets “repeats”.

Finally there is one office after the cursus honorum and that is the censorship. Two are elected every five years for an 18 month term in which they carry out the census. Election to the censorship generally goes to senior former-consuls and is one way to mark a particularly successful political career. That said, Romans tend to dream about the consulship, not the censorship and if you had a choice between being censor once or holding the consulship two or three times, the latter was more prestigious.

With the offices now laid out, we’ll go through them in rough ascending sequence. Today we’ll look at the military tribunes, the quaestors and the aediles; next week we’ll talk about imperium and the regular offices that carry it (consuls, praetors and pro-magistrates). Then, the week after that, we’ll look at at two offices with odd powers (tribunes of the plebs and censors), along with minor magistrates. Finally, there’s another irregular office, that of dictator, which we have already discussed! So you can go read about it there!

One thing I want to note at the outset is the “elimination contest” structure of the cursus honorum. To take the situation as it stands from 197 to 82, there are dozens and dozens of military tribunes, but just eight quaestors and just six praetors and then just two consuls. At each stage there was thus likely to be increasingly stiff competition to move forward. To achieve an office in the first year of eligibility (in suo anno, “in his own year”) was a major achievement; many aspiring politicians might require multiple attempts to win elections. But of course these are all annual offices, so someone trying again for the second or third time for the consulship is now also competing against multiple years of other failed aspirants plus this new year’s candidates in suo anno. We’ll come back to the implications of this at the end but I wanted to note it at the outset that even given the relatively small(ish) size of Rome’s aristocracy, these offices are fiercely competitive as one gets higher up.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part IIIa: Starting Down the Path of Honors”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-08-11.

1. See Lintott, op. cit. 104-5, n. 47.

2. These dates and numbers, by the by, follows F.P. Polo and A.D. Fernández, The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic (2019).

3. If you are wondering about how anyone can manage to hold the office before 27, given ten years of military service and 17 being the age when Roman conscription starts, well, we don’t really know either. The best supposition is that some promising young aristocrats seem to have started their military service early, perhaps in the retinues (the cohors amicorum) of their influential relatives. Tiberius Gracchus at 25 is the youngest quaestor we know of, but he’s in the army by at most age 16 with Scipio Aemilianus at Carthage in 146.