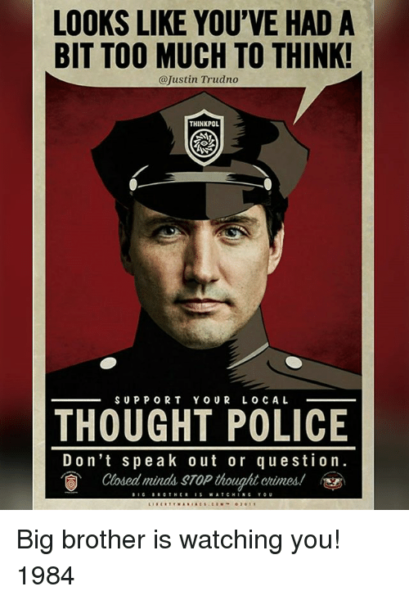

In The Line, Kevin Wiener explains another of the hidden “gems” of the Trudeau government’s ill-considered and repressive Online Harms Act that at least will please a few anti-immigration activists:

According to the Trudeau government and its defenders, the Online Harms Act is nothing to worry about. This is supposed to be a bill that will protect equity-seeking groups like racial minorities — yet one little-discussed provision will make millions of permanent residents open to deportation for even the most minor criminal offences, as long as a prosecutor can show that the crime was hate-motivated.

The resulting power to turn any crime into a deportable offence will make non-citizens — many of whom are racial and religious minorities — even more vulnerable in the criminal justice system compared to citizens.

The main focus of the Online Harms Act is regulating online platforms, but it also makes major changes to the way the criminal justice system deals with hate-motivated crimes. Under current law, if a crime is motivated by hate based on a protected characteristic, that’s considered an aggravating factor at sentencing. That means the judge can impose a higher sentence than they normally would, although they can never exceed the maximum sentence for the underlying crime. For many minor crimes, that maximum sentence is two years less a day.

The Online Harms Act uses a totally different approach to hate crimes. Rather than just being a sentencing factor, the Act would create a brand-new hate crime offence. Committing any crime, if motivated by hatred, would make someone guilty of a second crime, with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. To counter public concern, the Trudeau government has recently sent one of its senior advisors, Supriya Dwivedi, to argue that critics of this provision are “engaging in bad faith tactics”, going so far as to make the absolutely false statement that the bill won’t allow an increased sentence unless the underlying crime already had that sentence.

That is an accurate description of the current sentencing regime, but the text and clear purpose of the new bill is to let judges go further: a serious aggravated assault that might normally attract the maximum 14-year sentence can lead to life imprisonment if the attack was hate-motivated.

Further, Dwivedi’s defence of the bill ignores that maximum sentences play an important role in Canada’s immigration policy. If someone is neither a citizen nor a permanent resident, they can only be deported if they commit a more serious (called an “indictable”) offence, or two separate less serious (or “summary”) offences.

The new hate crime provision would be an indictable offence.