In The Line, Jen Gerson endures a foreign policy speech from Mélanie Joly that takes her on a weird journey through some of Canada’s earlier foreign policy headscratchers … usually leading back to Justin Trudeau’s late father:

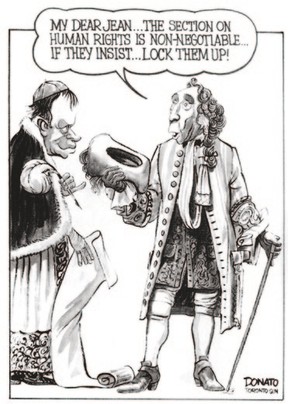

A Toronto Sun editorial cartoon by Andy Donato during Pierre Trudeau’s efforts to pass the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. You can certainly see where Justin Trudeau learned his approach to human rights.

If I saw a statue of P.E.T. on the roof of a foreign affairs building that looked like it were competing for a 10th place spot in the Eurovision tourney, I don’t know how I’d feel: embarrassed, touched, certainly too polite to say anything honest. I probably wouldn’t be so struck with awe by the sight that I’d be keen to shoehorn the anecdote into a major policy speech in front of the Economic Club.

And yet.

Joly’s speech was striking in that it could be divided into two distinct parts: The first half was a cogent and clear-eyed examination of the state of play of the world, one that acknowledged a fundamental shift in the assumptions that underpin the global order. Nothing one couldn’t glean from the Economist, but grounded nonetheless. The global order is shifting, the stakes have increased, and the world is going to be marked by growing unpredictability.

“Now more than ever, soft and hard power are important,” Joly noted, correctly, ignoring the fact that Canada increasingly has neither, and doesn’t seem to be doing much about that.

And this brings us to the second half of the speech, which was an attempt to spell out the way Canada will navigate this shift, by situating itself as both a Western ally and an honest broker: we are to defend our national interests and our values, while also engaging with entities and countries whose values and interests radically diverge from our own. “We cannot afford to close ourselves off from those with whom we do not agree,” Joly said. “I am a door opener, not a door closer.”

This was clearly intended to be analogous to the elder Trudeau’s historic policy of seeking cooperation with non-aligned countries — countries that declined to join either the Communist or the Western blocs throughout the Cold War.

[…]

If our closest allies treat us like ginger step-children as a result of our own obliviousness and uselessness, our platitude-spewing ruling class is going to seek closer relationships in darker places: in economic ties with China, and in finding international prestige via small and middling regional powers or blocs whose values and interests are, by necessity or choice, far more malleable than our own.

These cute turns of phrase are a matter of domestic salesmanship only. “Pragmatic diplomacy” is a thick lacquer on darker arts.

Which brings us back to Macedonia, again. Or North Macedonia, if you’re a stickler.

Before it declared independence in 1991, Macedonia was a republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During much of Trudeau Sr.’s time, Yugoslavia was led by Josip Tito, a Communist revolutionary who broke with Stalin and spearheaded a movement of non-aligned countries, along with the leaders of India, Egypt, Ghana, and Indonesia. Tito was one of several despotic and authoritarian leaders with whom Trudeau Sr. sought to ingratiate himself to navigate the global order.

P.E.T.’s most ardent supporters maintain a benevolent amnesia about just how radical Trudeau Sr. was relative not only to modern standards, but to world leaders at the time.

During the 1968 election, Trudeau promised to undertake a sweeping review of Canada’s foreign affairs, including taking “a hard look” at NATO, and addressing China’s exclusion from the international community.

In 1969, America elected Richard Nixon a bombastic, controversial, and corrupt president who forced Canada examine the depth of its special relationship with its southern neighbour. At the time, this was termed “Nixon shock.” And it could only have furthered Trudeau Sr.’s skepticism of American hegemony.

It was in this environment of extraordinary uncertainty, and shifting global assumptions and alliances, that Trudeau Sr. called for a new approach to Canadian foreign policy. He wanted a Canada that saw itself as a Pacific power, more aligned to Asia (and China). Trudeau also wanted stronger relationships with Western Europe and Latin America, to serve as countervailing forces to American influence.