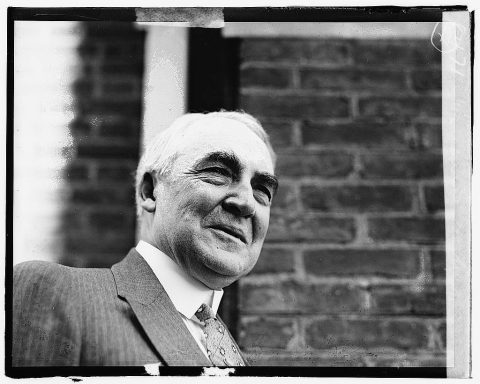

Warren G. Harding’s term in office has been treated like a punchline by progressive writers and commentators for a century, but Lawrence W. Reed refutes this easy mockery and points out that the winner of the 1920 election deserves much better:

Routinely dismissed as a bad chief executive, Harding’s reputation is undergoing a long overdue renovation. The latest contribution in that regard is a new, must-read biography by Ryan S. Walters titled, The Jazz Age President. Read it, and you’ll forever be skeptical of the lazy, biased, conventional historians who worship power and those who wield it.

Warren Harding didn’t just tell audiences what they wanted to hear. He sometimes told them what they did not want to hear. He went to Birmingham, Alabama to condemn racism and Jim Crow laws, for example — a fact I’ve previously pointed out.

Conventional historians praise Presidents for the bills they signed into law but often it requires more courage and conviction to veto them. On that score too, Harding can be judged favorably. He vetoed six bills in the 2-1/2 years he served in the White House. None of the six was overridden. That may not sound like a lot but remember, his party controlled both houses by big majorities; Congress didn’t send him much it thought he wouldn’t sign.

Four bills Harding vetoed concerned minor issues and generated little attention, but one concerned a bonus for veterans of World War I. It stirred up quite a fuss. As the bill worked its way through the House and Senate, Harding gave ample warning that he wouldn’t even consider a bonus that wasn’t paid for. Congress ignored him and sent the bill to his desk. He rejected it, noting as follows:

In legislating for what is called adjusted compensation, Congress fails to provide the revenue from which the bestowal is to be paid. We have been driving in every direction to curtail our expenditures and establish economies without impairing the essentials of governmental activities. It has been a difficult and unpopular task. It is vastly more applauded to expend than to deny.

After the Civil War, Congress paid pensions to veterans of the conflict and their dependents. Sixty years later, in 1923, it sent a bill to Harding to grant pensions to women who married aging Civil War veterans long after the war. It even authorized higher payments to them than what recent widows of veterans in the war with Germany were getting. His veto message included this unassailable objection:

The compensation paid to the widows of World War veterans, those who shared the shock and sorrows of the conflict, amounts to $24 per month. It would be indefensible to insist on that limitation upon actual war widows if we are to pay $50 per month to widows who marry veterans 60 years after the Civil War.

Congress should have known better than to expect Harding to sign such bills. This was the same man who declared at his modest, unembellished inauguration that “Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much of government”. He had expressed a desire to put “our public household in order”. He said he wanted “sanity” in economic policy, combined with “individual prudence and thrift, which are so essential to this trying hour and reassuring for the future”.

If somebody told me all that, I wouldn’t even think of asking him to approve a check for an able-bodied 30-year-old simply because she married an 80-year-old veteran.

This was the same Warren Harding, remember, who gave the country perhaps the best Treasury Secretary in its history, Andrew Mellon. According to historian Burton Folsom, Mellon slashed government expenses and eliminated an average of one Treasury staffer per day for every single day he held the office. Harding, Mellon and Calvin Coolidge (Harding’s successor), together with a friendly Congress, reduced the federal budget and cut the national debt by more than one-third.