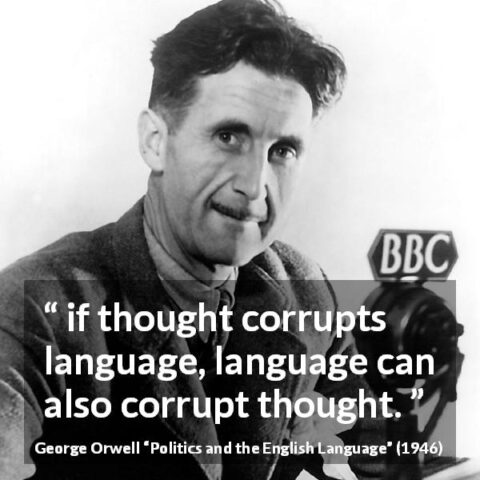

Christopher Gage suspects that George Orwell lived in vain:

In his essay, “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell lamented the decline in the standards of his mother tongue.

For Orwell, all around him lay the evidence of decay. Orwell argued sloppy language came from and led to sloppy thinking:

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language […] It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

With his effortless knack for saying in plain English the resonant and enduring, Orwell’s dictum is obvious as soon as uttered.

Orwell wrote that back in 1946. What would the author of Animal Farm and 1984 make of today’s standards?

“Misogyny” is overtaking “fascist” in the “I Don’t Own a Dictionary” championships.

Spend five minutes online, and you’ll encounter words defined in their starkest definitions. Words like “misogyny”, “misandry”, and “narcissist”, once possessed specific meanings. Now they mean whatever the speaker claims they mean.

The beauty of the English language lies in its precision. Sadly, those who populate the land which spawned the English language wield the language with all the grace and precision of a meat hook.

According to The Guardian, the recent Finnish election was suppurated with misogyny and fascism.

In that election, the one debased in misogyny and fascism, the losing incumbent Sanna Marin, a woman, won more seats in parliament than in 2019. The three candidates with the most votes — Riikka Purra, Sanna Marin and Elina Valtonen — were all women. Women lead seven of the nine parties returned to parliament — including the “far-right” Finns Party.

The Guardian didn’t permit reality to spoil a good headline.

As Orwell had it, “Fascism” is a hollow word. In the essay mentioned above, he said: “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’.” In modern parlance, the same applies to “misogyny”. “misandry”, “narcissism”, “gaslighting”, and just about every other buzzword shoehorned into a HuffPost headline.

“The beauty of the English language lies in its precision.”

This part is rather incorrect. As G. K. Chesterton pointed out, the beauty of the English language is that it is NOT precise. It is, in fact, a poetic language, full of metaphor and allusion and simile and alliteration and every other poetic device. One may argue (indeed, I hold this view) that much of this comes from ignorance–if you only know a few hundred words, you have to make those words work extremely hard in order for anyone to understand anything beyond the most basic concepts. But since this covers the vast majority of people that use English, it becomes significant. This fact can be demonstrated to one’s self, by the way–look at any scientific publication, or any legal brief–cases where we force English to be precise–and look at how difficult they are for the average reader. I’ll admit the jargon doesn’t help comprehensibility (though it does help my case, as jargon is necessary to increase precision), but even when jargon is lacking the language used is very different from the day-to-day.

English is a language of shades of meaning, a language that sidles up to but often does not directly approach the actual idea being conveyed. A language where emphasis on a particular syllable can change meaning. What it’s not, is precise!

Comment by Dinwar — June 14, 2023 @ 09:00

I’d hesitate before disagreeing with either Orwell or Chesterton, but English is a language with sufficient flexibility to be precise or to be poetic, thanks to all the “spare change” words we’ve lifted out of the linguistic pockets of so many other languages. I’m no poet, but I suspect writing poetry in English is somewhat easier than in many other languages thanks to our profusion of alternatives for so many words, each offering a slightly different interpretation to the reader/listener.

There have been many notions about creating a limited version of English for newcomers that — in theory — would allow them to carry on in an English-speaking society and be able to handle most basic interactions. (Orwell’s “Newspeak” is a more sinister take on that idea, intended to limit the ability of the proles to handle abstract ideas). I don’t think it would work with real people, because the nature of English usage always exposes newcomers to a wider vocabulary which then is added to the newcomer’s store of words for future use. They may not use them correctly, but they’re available for use.

Scientific and legal documents are almost always deeply jargonized because they’re not intended to be read by the average layperson, but by other initiates of the guild and one of the expectations of such initiates is that the language used be at least somewhat tailored to exclude the unwashed. Laws do not need to be written in ways that prevent easy understanding by those who will be governed by those laws, yet requiring them to be presented in a way that ordinary people can read them would reduce the need for lawyers.

Comment by Nicholas — June 14, 2023 @ 09:25

“There have been many notions about creating a limited version of English for newcomers that — in theory — would allow them to carry on in an English-speaking society and be able to handle most basic interactions.”

That’s a very different idea from what I was discussing. I was discussing the fact that many English speakers have a fairly limited vocabulary. This isn’t limited to English–large vocabularies are associated with education, something that only the rich had in the past–but English is particularly bad about it, since many of those extra words you mention are Greek and Latin, originating from a time when “literate” meant “able to read Greek and Latin” and when the language of upper-class England was French.

What I’m talking about is a toddler learning to speak; you’re talking about lobotomizing the language.

“Scientific and legal documents are almost always deeply jargonized because they’re not intended to be read by the average layperson, but by other initiates of the guild and one of the expectations of such initiates is that the language used be at least somewhat tailored to exclude the unwashed.”

No scientist that I know (and as a scientist, that’s not a small number) has ever coined a term with the intent of obfuscation. They simply do not write to exclude people. There is something of a push in some areas to coin a term to make a name for yourself, but the vast majority of the time jargon exists because there simply is no vernacular word for the thing in question. There is a certain amount of holdover from that time when all educated people knew Latin and Greek (science chose Latin as its lingua franca to INCREASE comprehensibility), and there’s a certain expectation that the audience is going to be actively reading and making attempts to understand, but by and large scientific papers are complex because the concepts are and vernacular English doesn’t work for them.

Your statement is slander against the scientific community, in other words, and contrary to all evidence from that community.

As for law, there’s probably more justification, but this is undermined by various attempts to put law in standard English. My understanding is that law is written the way it is because it needs to be precise and unambiguous, and needs to continue being so for several hundred years–not something that English is good at. Since English has no governing body (as opposed to such languages as French an Arabic), the language shifts over time, sometimes quite dramatically. Stilted, formulaic language is necessary to ensure comprehensibility in perpetuity.

Comment by Dinwar — June 14, 2023 @ 11:56

I did not mean to impugn the honour of scientists, but as fields become ever more specialized, the words in use within each field will tend to fall further and further from what non-scientists readily recognize and understand. “Jargon” is perhaps the wrong word as it carries connotations of deliberate obfuscation, but from an outsider’s view, meaning is harder to grasp as the language specialization moves away from ordinary mundane English.

They don’t write to deliberately exclude people, agreed. Yet the end result — because they are almost always writing to communicate with other specialists within their field or related fields — can’t help but be exclusionary. Latin was the language of science because early proto-scientists were educated by Catholic priests or monks for whom Latin was the language of the church. You could always communicate with any educated person in Christendom using Latin regardless of the differing vulgar tongues in use.

As for the law, it should strive to be as “precise and unambiguous” as possible, but as a recent study in MIT News summarized it:

Comment by Nicholas — June 14, 2023 @ 14:11