In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams notes that it’s just past 60 years since one of the most controversial documents the British government published during the latter half of the 20th century: The Beeching Report.

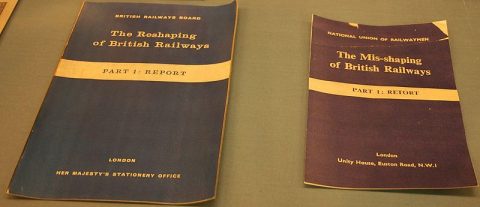

The British Railways Board’s publication The Reshaping of British Railways, Part 1: Report, Beeching’s first report, which famously recommended the closure of many uneconomic British railway lines. Many of the closures were implemented. This copy is displayed at the National Railway Museum in York beside a copy of the National Union of Railwaymen’s published response, The Mis-shaping of British Railways, Part 1: Retort.

Photo by RobertG via Wikimedia Commons.

Wednesday, 27 March 1963 marked the day when a civil servant with a doctorate in physics, seconded from ICI, proudly flourished a report he had written. That man was Dr Richard Beeching, and the result of his recommendations contained in The Reshaping of British Railways are with us to this day.

Beeching identified many unprofitable rail services and suggested the widespread elimination of a huge number of routes. He identified 2,363 stations for closure, along with 6,000 miles of track — a third of the existing network — with the loss of 67,700 jobs. His stated aim was to prune the railway system back into a profitable concern. Behind Beeching, seconded to the newly-established British Railways Board, stood the figure of the publisher-turned-Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan. He knew a thing or two about railways, having been a pre-nationalisation director of the Great Western Railway. It put him in the delightful position of never having to pay for a train ticket.

Macmillan observed from a shareholder’s point of view, “you can pour all in money you want, but you can never make the damned things pay for themselves”. In his view, the railway network and infrastructure of wagon works, tiny branch lines, cottages for signallers, crossings keepers and station masters, with most halts staffed 18 hours a day, amounted to a social service, albeit an expensive one. It had made the prosperity of Victorian Britain possible and was sustaining it still. From nationalisation in 1948, the railways themselves had attempted to make savings, closing 3,000 miles of track and reducing staff from 648,000 to 474,000. That famous Ealing comedy film of 1953, The Titfield Thunderbolt, about a group of villagers trying to keep their branch line operating after British Railways decided to close it, already reflected concern and railway nostalgia.

Britain’s literary and celluloid love affair with iron rails and steam began as long ago as 1905 with the publication of Edith Nesbit’s The Railway Children, a success which peaked when the book was made into a highly successful movie in 1970. Meanwhile, professional sleuths and loafers like Sherlock Holmes, Bulldog Drummond, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot and Bertie Wooster capitalised on the branch line network in their methodology of moving swiftly about pastoral England in their hunts for miscreants. It was the success of The Lady Vanishes, a 1938 mystery thriller set on a continental train, that launched Alfred Hitchcock as a world-class director. David Lean’s Brief Encounter of 1945, based on Noël Coward’s earlier one-act play, Still Life, attached deep romance to station platforms and waiting rooms, reminiscent of so much heartache in the recently fought world war. It is still regarded as one of the greatest of all British-made films. None of this mattered to Beeching, the man who was “Britain’s most-hated civil servant” at his death in 1985, a moniker still used today.

There’s an argument that Beeching was deliberately set up as a patsy for the real villains, Ernest Marples and Harold MacMillan:

The cold, dispassionate Beeching was absolutely the wrong man for the job. As he told the Daily Mirror at the time, “I have no experience of railways, except as a passenger. So, I am not a practical railwayman. But I am a very practical man.” John Betjeman, writing persuasively and eloquently in the Daily Telegraph each week, and later Ian Hislop, hit the right note in observing that Beeching, and all he stood for were technocrats. They “weren’t open to arguments of romantic notions of rural England, or the warp-and-weft of the train in our national identity. They didn’t buy any of that, and went for a straightforward profit and loss approach, from which we are still reeling today”.

However, it has also been argued that Beeching was the unwitting fall-guy for the Minister of Transport of the day, Ernest Marples. He was a self-made businessman who “got things done”, but he retained an air of shadiness about him. Macmillan should have known better. Marples had been managing director of Marples Ridgway, awarded contracts to build the first motorways. When challenged about a conflict of interest, he sold his 80 per cent shareholding to his wife. Elevated to the peerage, Marples fled to Monaco in 1975 to avoid prosecution for tax fraud. So, in some ways, the thing was a stitch-up. Marples directly benefited from the widespread cuts advocated by his subordinate, Beeching. Macmillan had his eye off the ball and was already considering retirement, hastened by an operation for prostate cancer six months after Beeching’s report.

The Prime Minister was astute enough to ensure the press presented the cuts in a positive way, however. From the Cabinet papers of the day, we now know the day before the publication of The Reshaping of British Railways, Beeching’s findings were rewritten to suggest the cuts were the first phase of a co-ordinated national transport policy, with advanced plans to replace the axed rail networks with improved minor roads and local bus services. In reality this was political fantasy (my inner lawyer cautions against more extremist language), for the bus-road subsidy would have cost more than that already paid to the railways. The promise of replacement bus services should have come with a guarantee of remaining in place for at least 10-15 years, because most were withdrawn after two, forcing more motor traffic onto an already inadequate road network.