Bruce Gudmundsson linked to this essay from “Shady Maples“, a serving officer in the Canadian Army, on the general topic of bullshit in the military:

Armies, as a rule, are quagmires of bullshit. The Canadian Army is no exception. We accept that bullshit is an occupational hazard in the Army, but it’s a hazard that we struggle to manage and it’s one that threatens our effectiveness as a force.

In order to understand bullshit we need a taxonomy, that is, a map of bullshit and the common varieties found in the wild. Using our taxonomy, we can develop diagnostic tools to detect bullshit and expose its corrosive effects on our integrity and professional culture. I assume that bullshit is also a hazard in other environments and government departments, but since my experience is in the land force I will be focusing my attention on that.

The subject of bullshit entered the mainstream in 2005 when Princeton University Press issued a hardcover edition of Harry G. Frankfurt’s 1988 essay “On Bullshit“. Frankfurt doesn’t mince words: “[one] of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his share.” He argues that even though we treat bullshit as a lesser moral offence than lying, it’s actually more harmful to a culture of truth. I believe this wholeheartedly, for reasons which will become clear.

In Frankfurt’s view, even though a liar and a bullshitter both aim to deceive their targets, bullshitting and lying require different mental states. In order to lie, someone must believe that they know the truth and intentionally make a false account of it. For example, if you believe that today is Monday but today is in fact Tuesday, and somebody asks you what day it is, you’re not a liar if you say “today is Monday”. You’re not lying because you really do believe that today is Monday, even though this belief is incorrect. In order to lie, you have to intentionally make a statement that is contrary to the truth as you understand it. In this example, you would be lying if you said “today is Tuesday” while believing that today is actually Monday. You would be accidentally correct, but you would still be lying because you are providing a false account of what you believe is true.

This means that lying actually requires a tacit respect for the truth on the part of the liar. The liar has to at least acknowledge the existence of truth in order to avoid it. To provide a false account of the truth, the liar must first believe in the truth.

The bullshitter, by contrast, does not operate under this constraint. Bullshit according to Frankfurt is speech without any regard for the truth whatsoever. To Frankfurt, “[the bullshitter] does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.” Bullshit, Frankfurt argues, is speech that is disconnected from a concern for truth. The bullshitter will say anything if it helps them achieve their desired ends.

[…]

Let’s move on to the topic of “bull”, which is discussed at length by British psychologist Norman F. Dixon, author of On the Psychology of Military Incompetence. Dixon beat Frankfurt to the punch by publishing his own theory of bullshit in 1976, twelve years before “On Bullshit”. Dixon is a Freudian psychologist writing in the 1970s, so I am skeptical of the scientific merit of his book. Nonetheless, he provides an interesting outsider’s perspective of British military culture from the Crimean War up to the Second World War and how that culture enabled terrible officers while punishing competent ones (spoiler: aristocrats and nepotism are bad for meritocracy).

There is an entire chapter of the book about bullshit as a contributing factor to military incompetence. Dixon attributes the origin of the word “bullshit” to Australian soldiers, who in 1916 “were evidently so struck by the excessive spit and polish of the British Army that they felt moved to give it a label”. His theory of the Australian origin of bullshit is supported by Australian philosopher David Stove, who believed that it’s a signature national expression.

[…]

Canadian political philosopher G. A. Cohen added some depth to the discourse when he responded to Frankfurt in “Deeper into Bullshit“. Cohen wasn’t satisfied that Frankfurt had explored full range of bullshit as a social phenomenon. Frankfurt anchors his definition of bullshit in the intention or mental state of the speaker (the bullshitter) whose lack of concern for truth is what makes their statements bullshit. Cohen responds to this by pointing out that there are many people who honestly profess their bullshit beliefs. Reading this brought me back to my undergrad days. I had a TA in a 300-level philosophy course who claimed that he doubted his own existence. Personally, I wondered whether he would still doubt his own existence if I punched him in the balls for spewing such performative bullshit in class. So I think that Cohen makes a good point: there are bullshitters who honestly believe their own bullshit.

Cohen’s argument is squarely aimed at a certain style of academic writing, which he calls “unclarifiable unclarity.” These are intentionally vague statements which cannot be clarified without distorting their apparent meaning or dropping the veil of profundity altogether. If you want an example, you can try reading Hegel or a postmodernist philosopher, or just save yourself the effort and click on this postmodern bullshit generator (trust me, it’s indistinguishable from the real thing). Pennycook et al. label statements of this type as “pseudo-profound bullshit“. Hilariously, they ran a series of experiments to see if test subjects would find the appearance of profound truth in both real and algorithmically-generated Deepak Chopra tweets. The result, disappointingly, was yes.

Cohen adds a fourth type of bullshit to our taxonomy: “irretrievably speculative comment”. Basically, when someone is arguing for a proposition which they have no way of knowing is true or false, or they put forward an argument that’s completely unsupported by readily available evidence, then that argument is bullshit.

[…]

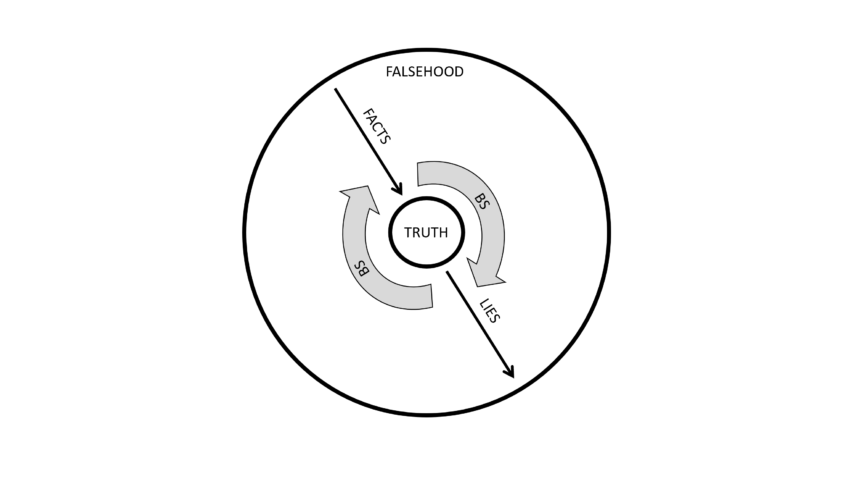

Still with me? So far we’ve identified and defined four types of bullshit (BS):

BS1 (Frankfurt): propositions made without concern for truth.

BS2 (Dixon): ritualistic activity which doesn’t serve its stated aim or justification.

BS3 (Cohen/Pennycook): unclarifiable unclarity aka pseudo-profound bullshit.

BS4 (Cohen): speculation beyond what’s reasonably permitted by the evidence.

The common denominator of all four types of bullshit is their disconnection from reality. Bullshit statements don’t enhance our understanding and bullshit activity doesn’t get us any closer to achieving our goals in the real world. Bullshit doesn’t necessarily move us further away from truth, like lies do, but it certainly doesn’t get us any closer to it either. Essentially, bullshit lowers the signal-to-noise ratio of discourse.