In The Critic, Alexander Larman looks back at one of the longest-running film series beginning with 1958’s Carry On Sergeant (not to be confused with the earlier — and reputedly terrible — interwar Canadian film of the same name) and continuing with many more until the filmic disaster of Carry On Emmanuelle in 1978 (there was also a 1992 attempt to revive the franchise, which failed):

In Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, it is decreed by the contrarian history master, Irwin, that “if George Orwell had lived, nothing is more certain than that he would have written an essay on the Carry On films”.

We are invited to take Irwin’s instructions that the Carry On films represent a valuable insight into British social history with suitable detachment. (The precise, suitably pompous quote is that “while they have no intrinsic merit, they acquire some of the permanence of art simply by persisting, and acquire an incremental significance if only as social history”.)

Yet Irwin (or Bennett) was almost certainly right that, had Orwell survived into the Sixties and Seventies, he would have found the Carry On film series both repellent and fascinating. It is literature’s, and history’s, loss that we do not have an account of Orwell’s thoughts on the antics of Charles Hawtrey, Kenneth Williams, Barbara Windsor et al.

In 1941, Orwell wrote of postcards by the cheerfully lowbrow artist Donald McGill that “your first impression is one of overpowering vulgarity” and that “what you are really looking at is something as traditional as Greek tragedy, a sort of sub-world of smacked bottoms and scrawny mothers-in-law which is a part of Western European consciousness”. He goes on to say that “jokes barely different from McGill’s could casually be uttered between the murders in Shakespeare’s tragedies”.

[…]

The joy of watching the Carry On films, then, is twofold. On the one hand, the hackneyed stories, two-dimensional characterisation and laboured puns and innuendo can be enjoyable, on a purely basic level, but hardly threaten to aspire to the levels of great art.

Yet on the other, the cheerfully Rabelaisian sentiments of the pictures — in which all men and women are defined purely in sexual and scatological terms — exist on a level of reductio ad absurdum.

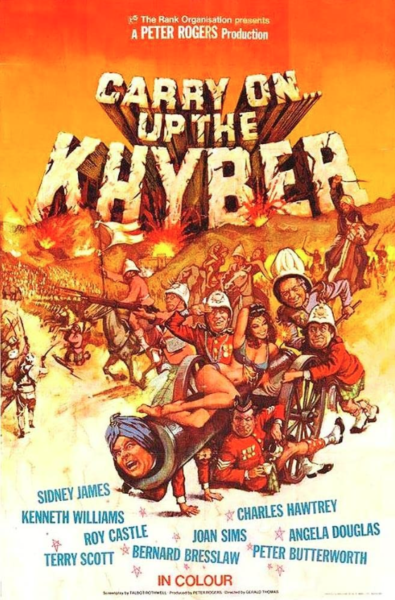

It is no coincidence that the best Carry On films contain a vein of social satire in their mocking of great British institutions, whether it be the NHS, MI5, the army or the Raj, and the final set piece of Carry On Up The Khyber — in which the stiff-upper-lip British occupiers ignore the Afghan invaders while taking formal dinner in black tie — rises to a level of surrealist genius that would have made Buñuel proud.

There is occasional talk of making another Carry On film, but with all the principal cast (save the ever-sprightly Dale) now dead and with the world a very different place, it is impossible to imagine that we will ever see, say, Carry On Tweeting or the like.

There is every possibility that a really top-notch cast could be assembled, if there was any serious intent behind it — I would love to see Andrew Scott, for instance, offer a more dynamic take on the kind of roles that Williams essayed, because he would do so brilliantly, and if the script could be written by the award-winning likes of Patrick Marber or Richard Bean, it could be a thing of innuendo-heavy beauty.

But then the Carry On series never was a thing of beauty. In its grim and hilarious way, it took every British national stereotype, pulled its trousers down, and gave it a hearty slap on its bare buttocks. Some might find this offensive; others might mourn its loss from public life.

In either case, we shall not look upon its like again. Dr Nookey, Francis Bigger, Professor Inigo Tinkle, Vic Flange: your services are no longer required. To which unkind cut we must solemnly say: “Ooh, matron.”