What are affairs like for poor spartiates?

What are affairs like for poor spartiates?

First, we need to reiterate that a “poor” spartiate was still quite well off compared to the average citizen in many Greek poleis – we talk about “poor” spartiates the same way we talk about the “poor” gentry in a Jane Austen novel. None of them are actually poor in an absolute sense, they are only poor in the sense that they are the poorest of the rich, clinging to the bottom rung of the upper class.

Nevertheless, we should talk about them, because the consequences of falling off of that bottom rung of the economic ladder in Sparta were extremely severe because of the closed nature of the spartiate system. Here is the rub: membership in a syssition was a requirement of spartiate status, so failure to be a member in a syssition – either because of failure in the agoge or because a spartiate could no longer keep up the required mess contributions – that meant not being a spartiate anymore.

The term we have for ex-spartiates is hypomeiones (literally “the inferiors”), which seems to have been an informal term covering a range of individuals who were (or whose family were) spartiates, but had ceased to be so. The hypomeiones were, by all accounts, mostly despised by the spartiates and the hatred seems to have been mutual (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6). Interestingly in that passage there – Xenophon’s Hellenica 3.3.6 – he lists the Spartan underclasses in what appears to be rising order of status – first the helots (at the bottom), then the neodamodes (freed helots, one step up), then the hypomeiones, and then finally the perioikoi. The implication is that falling off of the bottom of the spartiate class due to cowardice, failure – or just poverty – meant falling below the largest group of free non-citizens, the perioikoi.

Herodotus gives some sense of the treatment of men who failed at being spartiates when he details the two survivors of Thermopylae – Aristodemus and Pantites. Both had been absent from the battle under orders – Pantites had been sent carrying a message and Aristodemus had suffered an infection. When they returned to Sparta, both were ostracized by the spartiates for failing to have died – Pantites hanged himself (Hdt. 7.232) while Aristodemus was held to have “redeemed” himself with a suicidal charge at Plataea which cost his life (Hdt. 7.231). And as a side note: Aristodemus is the model for 300’s narrator, Dilios – so when you see him in the movie, remember: the Spartan system drove these men to pointless suicide because they followed an order.

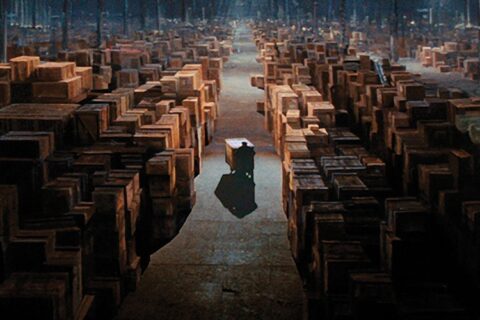

But my main point here is that falling out of the spartiate system meant social death. Remember that the spartiates are a closed class – failing at being a spartiate because your kleros is too poor to maintain the mess contribution means losing citizen status; it means your children cannot attend the agoge or become spartiates themselves. It means you, your wife, your entire family forever are shamed, their status as full members of society forever revoked and your social orbit collapses on you, since you are cut off from the very ties that bind you to your friends. No wonder Pantites preferred to hang himself.

In essence then, the core of the problem here is not that these poor spartiates were poor in any absolute sense – they weren’t. It was that the difference between being rich and being merely affluent in Sparta was a social abyss completely unlike any other Greek state. And that abyss was completely one way. As we’ll see – there was no way back.

Our sources are, unfortunately, profoundly uninterested in answering some crucial questions about the hypomeiones: did they keep their kleroi? What happened to the status of their children? What happened to the status of the women in their families? We can say one thing: it is clear that there was no “on-ramp” for hypomeiones to get back into the spartiate system. This is made quite clear, if by nothing else, by the collapsing number of spartiates (we’ll get to it), but also at the inability of extremely successful non-Spartan citizens – men like Gylippus and Lysander – to ever join the homoioi. Once a spartiate was a hypomeiones, they appear to have been so forever – along with any descendants they may have had. Once out, out for good.

All of that loops back to the impact of the great earthquake in 464. It is likely there were always spartiates who – because their kleroi were just a bit poorer, or were hit a bit harder by helot resistance, or for whatever reason – clung to the bottom of the spartiate system financially, struggling to make the contributions to the common mess. When the earthquake hit, the death of so many helots – on whom they relied for their economic basis – combined with the overall disruption seems to have pushed many of these men beyond the point where they could sustain themselves. Unlike in a normal Greek polis, they could not just take up some productive work to survive and continue as citizens, because that was forbidden to the spartiates, so they collapsed out of the class entirely.

(As an aside – the fact that wealthy spartiates, as mentioned, seemed to prefer each other’s company over the rest probably also meant that the social safety-net of the poor spartiates likely consisted of other poor spartiates. Perhaps in normal circumstances they remained stable by relying on each other (you help me in my bad year, I help you in yours – this is very common survival behavior in subsistence agriculture societies), but the earthquake – by hitting them all at once – may well have caused a downward spiral, as each spartiate who fell out of the system made the remainder more vulnerable, culminating in entire social groups falling out.)

As I said, our sources are uninterested in poor spartiates, so we can only imagine what it must have felt like, clinging desperately to the bottom of that social system, knowing how deep the hole was beneath you. One imagines the mounting despair of the spartiate wife whose job it is to manage the household trying to scrounge up the mess contributions out of an ever-shrinking pool of labor and produce, the increasing despair of her husband who because of the laws cannot do anything but watch as his household slides into oblivion. We cannot know for certain, but it certainly doesn’t seem like a particularly happy existence.

As for those who did fall out of the system we do not need to imagine because Xenophon – in a rare moment of candor – leaves us in no doubt what they felt. He puts it this way: “they [the leaders of a conspiracy against the spartiates] knew the secret of all of the others – the helots, the neodamodes, the hypomeiones, the perioikoi – for whenever mention was made of the spartiates among these men, not one of them could hide that he would gladly eat them raw” (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6; emphasis mine).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part IV: Spartan Wealth”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-29.