In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes picks up the story of the development of the steam engine (part one was linked here):

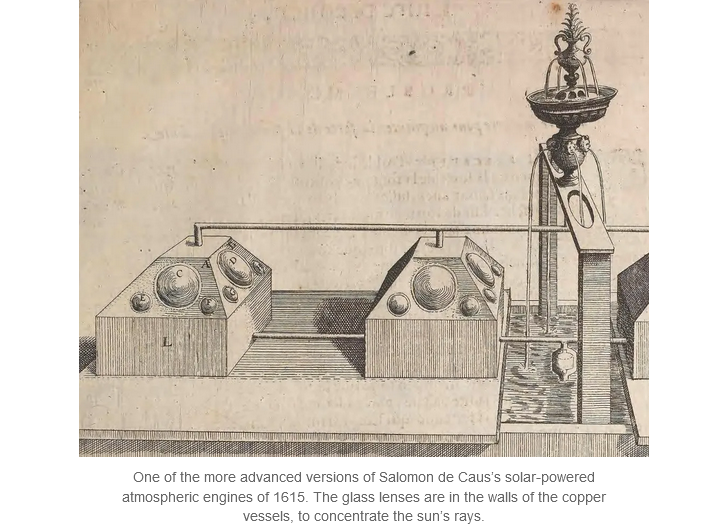

As I explained in Part I, the spark for my investigation was noticing that one Salomon de Caus, as early as 1615, had very probably made what amounts to a solar-powered version of Savery’s engine. By concentrating the sun’s rays on trapped air above the water in copper vessels, the resulting expansion of the trapped air and steam drove the water up a pipe to make a fountain flow. Most crucially of all, however, when the vessels cooled again they sucked water up and into them from a cistern below — a principle that de Caus also applied to having statues make music when the sun shone, and which he hinted may be useful for other things too.

Noticing this machine was a big shock to me, but de Caus’s invention was not even that original. It was actually an improvement of another, almost entirely ignored device described by Hero of Alexandria as early as the 1st Century, and which Hero in turn derived from one Philo of Byzantium who wrote in the 3rd Century BC.

Philo’s original device was very simple: a hollow leaden sphere with a bent tube rising out of it and into some water at the bottom of a jug. As the sun heated the sphere, the expanding air was pushed up the tube and into the jug’s water, escaping by bubbling out of the water. And crucially, when the sphere was removed from the sun and allowed to cool, the water was then drawn up the tube and into the sphere — Philo, about 1,900 years before Savery, had already encapsulated in a simple model the power of condensation to raise water.

Philo’s device was simple, but the principles it illustrated do appear to have been applied. Hero’s work, for example, includes a libas, or “dripper” fountain. In this alternative version of Philo’s apparatus, Hero connected the jug and sphere by two other pipes to a cistern underneath, as well as starting with some water already in the sphere. The jug now acted more like a funnel, into which the original bent tube now dripped its water like a fountain when the sun shone on the sphere. When cooled, however, the sphere replenished itself from the cistern underneath. It was almost exactly like de Caus’s version, which merely improved the strength of the fountain when it was heated, seemingly by replacing the lead with more heat-conductive copper and by using glass convex lenses to concentrate the sun’s rays.

Hero’s solar-powered dripping fountain doesn’t sound all that impressive, but both Philo and Hero appreciated the wider potential of its underlying principles.

Philo, for example, noted that it might make use of alternative heat sources: he described how his apparatus would work whether pouring hot water over the sphere, or by heating it over a fire. Once it cooled, it would always draw the water up.

Hero even suggested a mechanical use for the effect. By setting a fire on a hollow, airtight altar, the heated air within would flow down a tube into a sphere full of water, which in turn would be pushed up another tube into a hanging bucket. The bucket, when sufficiently heavy with water, would then pull on a rope to open some temple doors. Crucially, when the fire was extinguished, Hero noted that the cooling of the air in the altar would draw the water back into the sphere again, lighten the bucket, and so allow the doors to be closed by a counterweight. Although the condensing phase was really just for resetting the device, the fundamental ideas behind a Savery engine were already there: it raised water, used a fuel, and exploited condensation. It even did some light mechanical work.