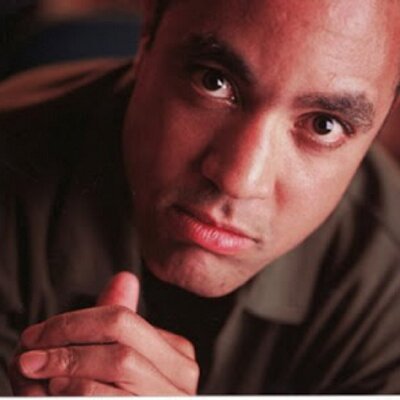

John McWhorter tackles the dreaded “N-word” — perhaps the most powerful taboo word in our current quasi-religious culture:

The question is why we have become so extremely sensitive about that word since the 1990s, despite that our times are so much further from the ones where whites casually levelled the term with abandon. Why are we making a finger-cross and hanging garlic in the doorway against even any semblance or suggestion of a sequence of sounds?

Supposedly because the word recalls slavery, Jim Crow and horrific abuses. But then, even black people just a few decades ago didn’t typically think this meant that one cannot utter the word even to refer to it. That’s new, and it is, quite simply, a taboo — as in what we associate with societies vastly different from our own.

There are languages in Australia where you use a separate vocabulary with your mother-in-law, and it is taboo to use the regular word equivalents for it with her. In one of the languages, there is a general word for moving that you use when talking to your mother-in-law about going, walking, sailing and crawling. To use the regular words for these things with her would be like hauling off with a curse word in English.

This sounds quaint to us, but should not, because our treatment of the N-word is hardly different. The idea that the word is simply never to be uttered is so deeply entrenched now that it may seem odd to many people under about 40 that in times that seemed quite modern not so long ago, one could produce the sounds of the word nigger in public if you were talking about it rather than using it. With taste, of course — one didn’t go about saying it over and over. But there was an understanding that to refer to it — especially since this was usually in condemnation — was harmless. Because it was.

If you think about it, this made perfect sense. It’s today’s situation that is odd, in that suddenly we have a taboo of a kind we associate with pre-scientific indigenous societies. The word must be chased away whenever it seeps in through the cracks in the floor, just as if you pick up the phone and the Devil is on the line, you hang up. To wit, this is more evidence that Electness is a religion. The evolution in sensibility about the N-word has been an early manifestation of Elect ideology, penetrating so quickly because of the especially loaded nature of the word. It’s pretty easy to classify it as heresy for saying a word that is used as a slur; getting people fired for saying reverse racism — as happened to former San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Gary Garrels — takes a while.

Some will despise that I am calling the new take on the word pious. But 25 years ago we all knew exactly those things about the word’s heritage, and felt modern and enlightened to, with sensible moderation, utter the word in reference rather than gesture. Under normal conditions, the etiquette would have stayed at that point. The only thing that makes that take on the word now seem backwards is a sense of outright “cover-your-mouth” taboo: i.e. religion. This performative refusal to distinguish, this embrace of the mythic, shows a take on the N-word analogous to taking the Lord’s name in vain.

I call this refusal performative — i.e. a put-on — because I simply cannot believe that so many people do not see the difference between using a word as a weapon and referring to the word in the abstract. I would be disrespecting them to suppose that they don’t get this difference between, say, Fuck! as something yelled and fuck as in a word referring to sexual intercourse. They understand the difference, but see some larger value in pretending that it doesn’t exist.

In my experience, a common idea is that if we allow the word to be used in reference, there is a slippery slope from there to whites feeling comfortable hurling the slur as well. There are two problems with this point. One: for decades civilized people could use the word in reference, and yet there was no sign of the epithet coming back into style. Today’s crusaders can’t claim to be holding off some rising tide. Second: what is the sociohistorical parallel? At what point in human history has a slur been proscribed, but then returned to general usage because it was considered okay to refer to the word as opposed to use it? That many people can just imagine this happening with the N-word is not an argument, especially since it’s hard not to notice that this hypothetical scenario fits so cozily into their professionally Manichaean take on race.