In the latest installment of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention, he looks at the multiple crises that afflicted England in the mid-sixteenth century and some of the reactions to those setbacks:

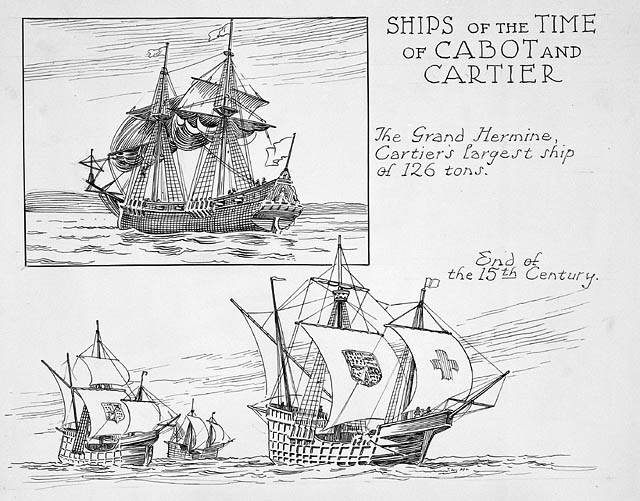

Ships from the period of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) and Jacques Cartier.

Illustration by Thomas Wesley McLean (1881-1951) via Wikimedia Commons.

From the 1540s through to the 1560s, [England] was beset by religious uproar, high inflation, hunger, rural and then urban unemployment, a fall-off in its major export trades, and widespread unrest. It was diplomatically isolated too. And I did not even mention the epidemics: the terrifying “sweating sickness” returned in 1551, deadly influenza swept the country in 1557, and in 1563 some 17,000 people in London were reportedly killed by the plague.

Yet, in the face of such problems, innovation in England began to pick up pace. The country, having once been a scientific and technological backwater, began to show signs of catching up. Why?

[…] The fall-off in trade with Europe, for example, seems to have had something to do with spurring the voyages of exploration in search of a north-west and north-east passage to the East Asia. Having lost Antwerp as a place to sell cloth in 1551, the English went in search of an arctic route to northern China and Japan. The expert geographers believed that those regions had a similar climate to that of Antwerp and the surrounding Netherlands, and so reasoned that the Japanese would therefore demand the same kinds of cloth. Although the English expeditions from 1553 onwards did not find a passage to Japan, they did establish trade routes with Russia via the White Sea, and they began to more actively consider the exploration and colonisation of North America. More importantly, with those voyages of exploration came greater experience of navigation, and it was not long before English ships were circumnavigating the globe (Francis Drake in 1577-80). Improvements to navigational techniques and instruments, as well as the ships themselves followed.

So it is tempting to think that necessity was initially the mother of invention, and that the many navigational and shipbuilding improvements of late-sixteenth-century England were its result. But I don’t think that this narrative quite works. I do not believe that necessity was the mother of invention.

For a start, voyages of navigation had already been attempted a number of times, long before the more successful ones in the early 1550s. The first explorers had reputedly gone west from Bristol in 1465, and certainly from 1480. And soon after the announcement of Columbus’s discoveries in the 1490s, the Venetian Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot), had sailed from Bristol with Henry VII’s blessing and claimed Newfoundland for both crown and Catholicism. Cabot had even hoped to found a penal colony on his second voyage in 1497, though for some reason the king did not provide the criminals. Throughout the early sixteenth century, the voyages continued. John Rastell, brother-in-law to Thomas More, the famous statesman and author of Utopia, in 1517 went in search of a north-west passage (though he never got beyond Ireland, because his crew decided it would be better to leave him there and sell the ship’s cargo in Bordeaux). Yet another voyage went west with Henry VIII’s support in 1527, but it mostly just found other Europeans — fishing fleets from Spain, Portugal, and France off the coast of Newfoundland (the English had made some catches there in the early 1500s, but apparently could not compete), and the Spanish everywhere else. The expedition made its way down to the Caribbean and then went home, with little to report. So people had already gone off exploring, long before the mid-sixteenth-century English commercial crisis. It suggests that there had already been both a latent supply and demand for such explorations.