Lindybeige

Published 4 Mar 2015Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

More videos here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…There were so many types of hat in the past, and yet it turns out that many of them were actually the same.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

November 25, 2019

Historical hats

More frequent car fires, an unintended consequence of wider adoption of electric vehicles

In Quadrant, Tim Blair recounts the story of a friend crossing the Sydney Harbour Bridge only to find his vehicle was on fire:

Most of us manage to scrape through life with no such flame-related driving incidents. Future motorists, however, may find themselves more frequently enjoying the occasional car-b-que. That’s because electric cars — the things Labor ruinously attempted to force upon us as part of their spectacular 2019 election campaign disaster — seem to be impressively prone to burning.

Now, an ordinary car fire is not really that big a deal. Catch it early enough and it can be quickly dealt with. But a fire involving an electric car is a whole different matter. Those things are like four-wheeled infinity candles.

In the manner of all the money given to its manufacturer by various governments, an electric Tesla recently torched itself in Austria. The Tesla’s fifty-seven-year-old driver had slid off the road and struck a tree, prompting a fire emergency.

In ordinary car blaze cases, a single fire engine or even a personal fire extinguisher is sufficient to deal with the problem. Electric cars, or EVs, demand slightly more attention when combustion occurs. Here’s an online news account:

In order to put out the fire, the street had to be closed and fire authorities had to bring in a container user to cool the vehicle.

Some 11,000 litres of water are needed to finally extinguish a burning Tesla but an average fire engine only carries around 2,000 litres of water.

The container used is said to be suitable for all common electric vehicles. It measures 6.8 metres long, 2.4 metres wide and 1.5 metres high, it is (obviously) waterproof and weighs three tons.

Moreover, “fire brigade spokesman Peter Hölzl warned that the car could still catch fire for up to three days after the initial fire”.

I’ve owned one or two cars that were sensibly equipped with fire extinguishers. Future motorists may wish to tow around a lake, just in case their earth-friendly electric cars decide to go the full kaboom.

YouTube vs Grey: A Ballad of Accidental Suspension

CGP Grey

Published 24 Nov 2019Join my email list: http://www.cgpgrey.com/email

Follow me on Twitter: https://twitter.com/cgpgrey

How to Be an Epicurean

In City Journal, Michael Gibson reviews a recent book on Epicureanism by Catherine Wilson:

The Atomic Age had its anxieties, but Hugh Hefner believed he had a good diversion. “We aren’t a family magazine,” he announced in the first issue of Playboy in 1953. “We enjoy mixing up cocktails, an hors d’oeuvres or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.” By the 1960s, the music had grown louder, the colors more lurid, the conversations steamier. When Hefner died in 2017, he was considered either a hero of hedonism or an object lesson in the period’s squalid obsessions. Run a Google search today on Hefner, and you’ll often find the word “Epicurean” to describe him. Is this fair to Epicurus, the man who set forth the philosophy starting in 306 BC?

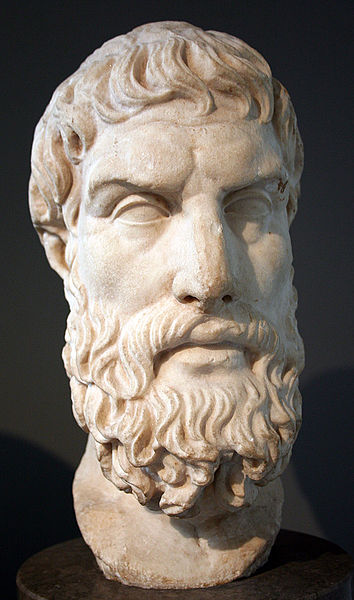

Marble bust of Epicurus. Roman copy of Greek original, 3rd century BC/2nd century BC. On display in the British Museum, London.

Photo by ChrisO via Wikimedia Commons.For 23 centuries now, Epicureans have struggled mightily against variations of the Hefner caricature. If pleasure is the highest good, the goal of the best life, must we all strive to live in pajamas, smoking a pipe in a decadent Hollywood Hills estate? Though he didn’t live in a mansion off Sunset Boulevard, at the end of the fourth century BC, at the age of 32, the philosopher Epicurus founded the Garden, a school removed from Athens’s monuments of power and politics. An inscription at the entrance read: “Stranger, here you will do well to stay; here our highest good is pleasure.” (In Chicago, Hefner’s door bore an inscription: Si Non Oscillas, Noli Tintinnare, or “If you don’t swing, don’t ring.”)

Leading life in a modern Garden is the subject of Catherine Wilson’s latest book, How to Be an Epicurean: The Ancient Art of Living Well. There was always an air of Peter Pan-like anarchy at the Playboy Mansion, but as Wilson shows us, life in the Garden was quite different. Her book is a spirited tour and defense of Epicurean philosophy, as reconstructed by the fragments Epicurus left behind in tattered papyrus and as set forth in the epic poem De Rerum Natura, “On the Nature of Things,” by the Roman poet Lucretius.

What did these pleasure-seekers believe? They start with the elementary particles, atoms — tiny, colorless, without smell, shaped this way and that, indestructible, reshuffling themselves infinitely into all the marvelous forms we see, including ourselves. Their forms get swept away by time, only to recombine again into something new — possibly another universe. Blurred in this haze of metaphysics, most atoms fall straight downward into the void, but a few swerve, and from these deviations arise our free will and all that we see. At the California Institute of Technology, physicist Richard Feynman began his lectures by wondering what single sentence would be passed on to future generations, if, in a cataclysm, all scientific knowledge was destroyed. His answer: “The atomic hypothesis that all things are made of atoms.”

With the Epicureans, we have a historical test of Feynman’s thought. The world is made of nothing more than atoms in the void, but where did that take the ancient Greeks and Romans who believed it? Wilson begins with these basic building blocks because she asserts that mistaken beliefs about nature are the source of our deepest fears and hang-ups: death, punishment in an afterlife, failure in this one, lust for power, greed, jealousy, unrequited love, and status-jockeying. “Epicurean philosophy might be said to be based on the notion of the limit,” Wilson writes. By understanding the atom and the void, by knowing that the soul is mortal and the gods indifferent, that all things pass and are forgotten, we might then liberate ourselves from the grinding weight of superstition and the vanity of ambition and pursue pleasure without guilt.

Why Can We See Through Glass? | Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published 24 Jan 2013Why can we see through glass, but not other solid objects? James May explains.

Subscribe to Earth Lab for more fascinating science videos – http://bit.ly/SubscribeToEarthLab

All the best Earth Lab videos http://bit.ly/EarthLabOriginals

Best of BBC Earth videos http://bit.ly/TheBestOfBBCEarthVideosHere at BBC Earth Lab we answer all your curious questions about science in the world around you. If there’s a question you have that we haven’t yet answered or an experiment you’d like us to try let us know in the comments on any of our videos and it could be answered by one of our Earth Lab experts.

QotD: The origins of the state

Taxation most likely began ten thousand years ago, when nomadic hunter-gatherers gave up their wandering ways — and the tools associated with them — settled down, and started growing crops and herding livestock, which requires an entirely different suite of tools than hunting. The hunter-gatherers’ tools could be used as weapons because that’s essentially what they were — ask any mastodon — the farmers’ could not. As a result, anti-productive marauders who had been held off by the hunters’ tools (or the ability of the hunters and their families to escape and evade) took advantage of those who were stuck to the plots of land they had learned to farm with clumsy agricultural implements (which could not be wielded as easily by females, relegating them to a subordinate role for fifty centuries), and forced to to pay tribute to the bandits. Go take another look at the 1960 movie masterpiece The Magnificent Seven for illustration. The thieves eventually learned to call themselves “government” and the goods they stole, “your fair share”.

L. Neil Smith, “What Would Real Tax Reform Look Like?”, Libertarian Enterprise, 2017-10-29.