Phillip Magness recounts his experiences on Twitter when he pointed out that a major work that the New York Times used in their 1619 Project suffers from some significant statistical problems:

About a week ago I began scrutinizing how the New York Times‘ 1619 Project relied upon the work of the controversial “New History of Capitalism” genre of historical scholarship to advance a sweeping indictment of free markets over the historical evils of slavery. The problems with this literature are many, and prominent among them is its use of shoddy statistical work by Cornell University historian Ed Baptist to grossly exaggerate the historical effect of slave-produced cotton on American economic development. Baptist’s unusual rehabilitation of the old Confederacy-linked “King Cotton” thesis is unsupported by evidence and widely rejected by economic historians. His book The Half Has Never Been Told has nonetheless acquired a vocal following among historians and journalists, including providing the basis of a feature article in the Times series on slavery.

Curious about the following Baptist’s work had acquired despite its clear problems, I presented several questions on Twitter for its enthusiasts in the academy.

Were they aware that Baptist’s statistics, including his estimate of slavery’s share of the antebellum economy, arose from a documented mathematical error? Did they know his thesis had been scrutinized by leading economic historians, who found problems of misrepresented evidence and citations to documents that did not support what Baptist claimed? Had Baptist made any effort to respond to his critics? Or, more importantly, had he corrected his statistical mistakes, which continue to be cited in the press, in academic works, and even in congressional hearings on the legacy of slavery despite their inaccuracy?

Unless you’re new to the social media cesspit, you won’t be surprised to find out that his inquiries generated a lot of heated responses, including some academics indulging in “keyboard warrior” tactics to discredit him while avoiding engaging with the points he was attempting to raise.

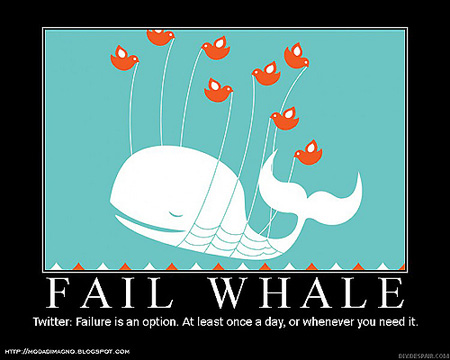

Social media brings with it a mixed bag of everything from intellectual exchange to juvenile antics to a corrosive undermining of basic discourse, as my colleague Max Gulker recently catalogued. But there also seems to be something about Twitter that brings out the very worst in academics.

A quick foray onto the site and a few minutes of reading will provide ample evidence that Araujo’s outburst is not atypical among the regulars of History Twitter. Or Econ Twitter. Or English, Philosophy, and Sociology Twitter. Politics are often, though not always, the occasion, which in practice translates into distinguished professors at elite institutions striving their hardest to reduce themselves to intellectual parity with a certain presidential account’s own notorious stream of insults and derision.

The more disturbing examples come from the medium’s effects on scholarly discussion though.

In theory, a functional academic Twitter community would permit intellectuals to instantaneously present their ideas before peers all over the world and receive real-time feedback on research discoveries or scholarly challenges to controversial ideas. They could tap the expertise of others for suggestions on roadblocks in the processes of scholarly production. They could solicit constructive criticism from opponents. Or they could challenge problematic arguments in the existing literature, prompting scholars to examine the strengths and weaknesses of each. Imagine a global conference or seminar room where you can not only find academic peers working on common interests, but also solicit their advice — or push back against contested areas of their work.