In New York magazine, Andrew Sullivan portrays the current state of the American Republic in light of the late history of the Roman Republic:

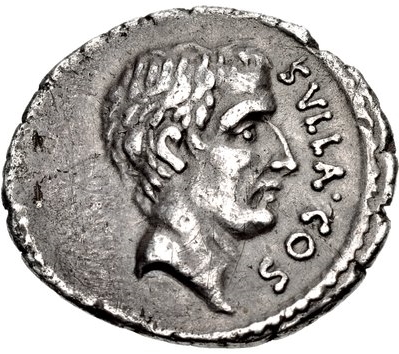

This 54 B.C. coin bears the portrait of the dictator Sulla. The moneyer was Q. Pompeius Rufus, the grandson of Sulla and his home would likely have had portraits of their famous ancestor. Thus, although posthumously struck, the portrait on these coins is probably an accurate representation.

Photo by CNG via Wikimedia Commons.

… zoom out a little more and one obvious and arguably apposite parallel exists: the Roman Republic, whose fate the Founding Fathers were extremely conscious of when they designed the U.S. Constitution. That tremendously successful republic began, like ours, by throwing off monarchy, and went on to last for the better part of 500 years. It practiced slavery as an integral and fast-growing part of its economy. It became embroiled in bitter and bloody civil wars, even as its territory kept expanding and its population took off. It won its own hot-and-cold war with its original nemesis, Carthage, bringing it into unexpected dominance over the entire Mediterranean as well as the whole Italian peninsula and Spain.

And the unprecedented wealth it acquired by essentially looting or taxing every city and territory it won and occupied soon created not just the first superpower but a superwealthy micro-elite — a one percent of its day — that used its money to control the political process and, over time, more to advance its own interests than the public good. As the republic grew and grew in size and population and wealth, these elites generated intense and increasing resentment and hatred from the lower orders, and two deeply hostile factions eventually emerged, largely on class lines, to be exploited by canny and charismatic opportunists. Well, you get the point.

After the overthrow of the monarchy, the new Republic went from strength to strength, struggling against and generally beating and absorbing other city states in the Italian peninsula, eventually rising to face the challenge of Carthage, the dominant power in the western Mediterranean. The eventual Roman victory over Carthage left Rome the superpower of its age, able to dominate and control even the remaining “great” powers of the eastern Mediterranean world. One of the costs of military dominance was an over-reliance on its citizen armies, which eventually changed the entire economy of the Republic, switching from largely small-holding farmers (who were subject to legionary service) to larger slave-worked farms that displaced the families of free citizens from their lands. The result was a constant inflow of impoverished rural citizens to the urban centres, especially Rome itself.

The newly enlarged urban poor found champions to push for reforms to aid them in their plight, the first of whom was Tiberius Gracchus (Extra Credits did a short video series on the Brothers Gracchi: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, and an extra commentary video). The defeat and death of the Gracchi brothers by agents of the Patrician order led, as you might expect, to yet more polarization and further violent political struggle. This process was hastened by the conflict between Marius and his former protégé Sulla:

As the turn of the first century BCE approached and wars proliferated, with Roman control expanding west and east and south across the Mediterranean, the elites became ever wealthier and the cycle deepened. Precedents fell: A brilliant military leader, Marius, emerged from outside the elite as consul, and his war victories and populist appeal were potent enough for him to hold an unprecedented seven consulships in a row, earning him the title “the third founder of Rome.” Like the Gracchi, his personal brand grew even as republican norms of self-effacement and public service attenuated. In a telling portent of the celebrity politics ahead, for the first time, a Roman coin carried the portrait of a living politician and commander-in-chief: Marius and his son in a chariot.

A dashing military protégé (and rival) of Marius, Sulla, was the next logical step in weakening the system — a popular and highly successful commander whose personal hold on his soldiers appeared unbreakable. Tasked with bringing the lucrative East back under Rome’s control, he did so with gusto, prompting a somewhat nervous Senate to withdraw his command and give it to his aging (and jealous) mentor Marius. But Sulla, appalled by the snub, simply refused to follow his civilian orders, gathered his men, and called on them to march back to Rome to reverse the decision. His officers, shocked by the insubordination, deserted him. His troops didn’t, soon storming Rome, restoring Sulla’s highly profitable command, and forcing his enemies into exile. Sulla then presided over new elections of friendly consuls and went back into the field. But his absence from Rome — he needed to keep fighting to reward his men to keep them loyal — enabled a comeback of his enemies, including Marius, who retook the city in his absence and revoked Sulla’s revocations of command. Roman politics had suddenly become a deadly game of tit for tat.

When Sulla entered Rome a second time, he rounded up 6,000 of his enemies, slaughtered them en masse within earshot of the Senate itself, launched a reign of terror, and assumed the old emergency office of dictator, but with one critical difference: He removed the six-month expiration date — turning himself into an absolute ruler with no time limit. Stocking and massively expanding the Senate with his allies, he neutered the tribunes and reempowered the consuls. He was trying to use dictatorial power to reestablish the old order. And after three years, he retired, leaving what he thought was a republic restored.

Within a decade, though, the underlying patterns deepened, and nearly all of Sulla’s reforms collapsed. What lasted instead was his model of indefinite dictatorship, with the power to make or repeal any law. He had established a precedent that would soon swallow Rome whole.