Leonid Sirota provides some interesting background on the rise of the administrative state during the 1930s:

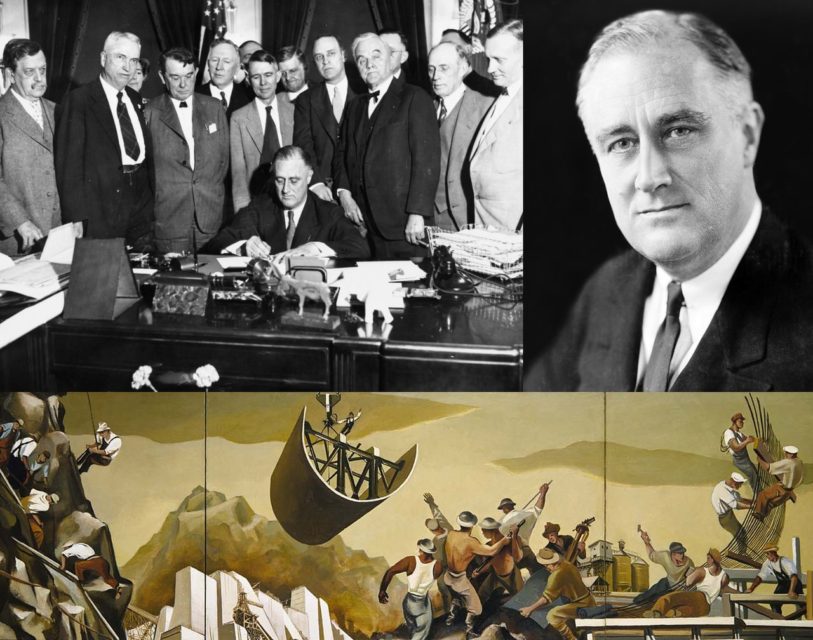

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

To a degree that is, I think, unusual among other areas of the law, administrative law in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Canada is riven by a conflict about its underlying institution. To be sure there, there are some constitutional lawyers who speak of getting rid of judicial review of legislation and so transferring the constitution to the realm of politics, rather than law, but that’s very much a minority view. Labour unions have their critics, but not so much among labour lawyers. But the administrative state is under attack from within the field of administrative law. It has, of course, its resolute defenders too, some of them going so far as to argue that the administrative state has somehow become a constitutional requirement.

In an interesting article on “The Depravity of the 1930s and the Modern Administrative State” [PDF] recently published in the Notre Dame Law Review, Steven G. Calabresi and Gary Lawson challenge the defenders of the administrative state by pointing out its intellectual origins in what they persuasively argue was

a time, worldwide and in the United States, of truly awful ideas about government, about humanity, and about the fundamental unit of moral worth—ideas which, even in relatively benign forms, have institutional consequences that … should be fiercely resisted.

That time was the 1930s.

Professors Calabresi and Lawson point out that the creation of the administrative state was spearheaded by thinkers ― first the original “progressives” and then New Dealers ― who “fundamentally did not believe that all men are created equal and should democratically govern themselves through representative institutions”. At an extreme, this rejection of the belief in equality led them to embrace eugenics, whose popularity in the United States peaked in the 1930s. But the faith in expertise and “the modern descendants of Platonic philosopher kings, distinguished by their academic pedigrees rather than the metals in their souls” is a less radical manifestation of the same tendency.

The experts, real or supposed ― some of whom “might well be bona fide experts [while] [o]thers might be partisan hacks, incompetent, entirely lacking in judgment beyond their narrow sphere of learning, or some combination thereof” ― would not “serve as wise counselors to autonomous individuals and elected representatives [but] as guardians for servile wards”. According to the “advanced” thinkers of the 1930s, “[o]rdinary people simply could not handle the complexities of modern life, so they needed to be managed by their betters. All for the greater good, of course.” Individual agency was, in any case, discounted: “the basic unit of value was a collective: the nation, the race, or the tribe. Individuals were simply cells in an organic whole rather than ends in themselves.”

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.