An interesting article in Vox, suggesting that the gradual unification of all the German principalities, electorates, duchies, counties, bishoprics, free cities, and miscellaneous other semi-independent bits and bobs of the Holy Roman Empire was not inevitable and that — absent British blundering after the Napoleonic wars — it would have produced a very different 20th century:

The Holy Roman Empire in 1789, before Napoleon “rationalized” hundreds of smaller entities into the Confederation of the Rhine.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.

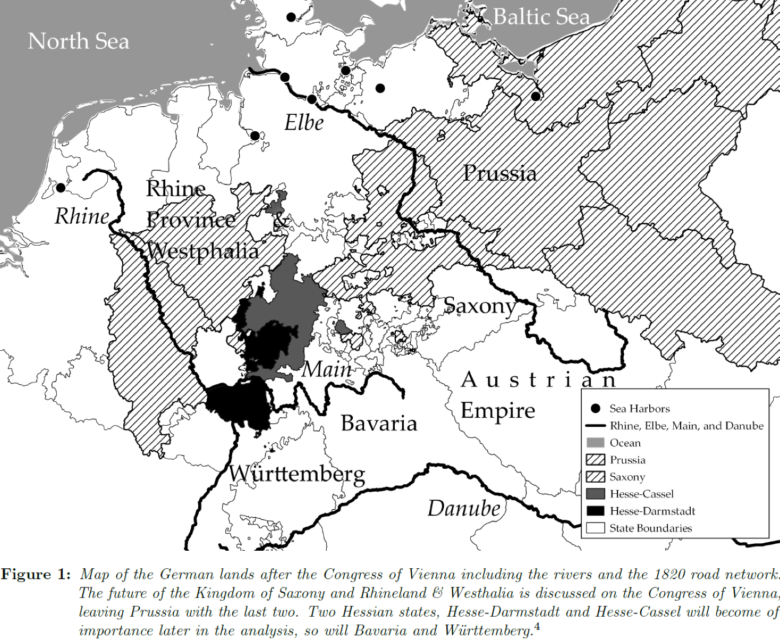

The boundaries of states are the heart of many recent debates, be it the European refugee crisis, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), or Brexit (Snower and Langhammer 2019). After decades of stability, today we are again seeing heated discussions about the shape and extent of political borders. Clearly, borders are neither naturally given nor random. In Europe and elsewhere, the current state borders have been formed and changed over centuries, sometimes peacefully, often in bloody wars. In Huning and Wolf (2019), we look at the formation of the German nation state led by Prussia and trace it back to a change in borders decided at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15.

In a nutshell, we have two findings:

- First, the geographic position of a state can be a crucial factor for institutional change and development.

- Second, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 under Prussian leadership was a truly European story, involving Britain, the Russian Empire, and the Belgian revolution of 1830/31. We show in particular that the Zollverein formed as an unintended consequence of Britain’s intervention in 1814/15 to push back Russian influence over Europe.

In theory, why would the geographic position of a state relative to that of other states matter? Intuitively, it should matter as long as the costs of trade and factor flows depend on their routes. If a large share of my trade has to pass the territory of one or several neighbours, my trade and trade policy will depend on the trade policy of my neighbours. Moreover, if tariffs are levied not only on imports but also on transit trade, as was general practice until the Barcelona Statute of 1921 (Uprety 2006), policymakers face the problem of multiple marginalisation, which is well known from the literature on supply chains. In our work, we provide a simple theoretical framework (in partial equilibrium) to show how the location of a revenue maximising state planner will affect its ability to set tariffs. Some states can increase their tariff revenue at the expense of their hinterland. Next, we show that a customs union can be beneficial for a group of states exactly because it solves the problem of multiple marginalisation.

A major challenge to testing our idea empirically is that a state’s political boundaries (and hence its location) do not change very often, and if they do, the change is unlikely to be unrelated to trade or factor flows. However, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 can be considered as a quasi-experiment. Let us briefly revisit this historical episode. At the end of the Napoleonic wars of 1792-1814/15, only Russia and the UK were left as major military powers. Habsburg, Prussia, and the defeated France attempted to consolidate their positions at the expense of the many smaller states that had just about survived the wars, notably the former allies of Napoleon such as Saxony and Poland. Overall, the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna in 1814 were dominated by military-strategic considerations between the two great powers. Russia wanted to expand westwards, Prussia was desperate to annex the populous Kingdom of Saxony, which bordered Prussia in the south and would create a large and coherent territory. To this end, Prussia was willing to give up not only her Polish territories to Russia, but also her positions and claims on the Rhineland (Müller 1986). This met stiff resistance from Britain, joined by Habsburg and France, which feared a new Russian hegemony on the continent – the ‘Polish Saxon question’. After weeks of diplomatic struggle, the outcome was a division of Saxony, another division of Poland and Prussia being established as the “warden of the German gate against France” (Clapham 1921: 98). Figure 1 shows the result of these negotiations.

H/T to Continental Telegraph for the link.