If you’ve been following the blog for a while, you’ll know that I’ve long been skeptical of any official economic statistics coming out of China. The reasons for my skepticism are that vast areas of the Chinese economy were owned or controlled by the state and reporting from those entities was performed through layers of officials whose positions and personal well-being depended on those reports being as positive as possible. In a capitalist system, announcing false production or profit figures will eventually be detected (sometimes not as soon as we’d like), and the company loses the trust of customers, suppliers, and banks, making survival much more difficult. In a state-owned organization, everyone in the hierarchy has a vested interest in false information not being uncovered or reported. In a private firm, you could lose your job … in a state-run enterprise, you could be shot or sent to a “re-education camp” along with all your family. The incentive to lie is much stronger when your risks are that high.

Tim Worstall comments on a recent report that compares the performance over time of Chinese private companies, privatized state companies, and companies that are still state-run:

That China has relaxed the governmental grip upon industry in recent decades is true. That China has become very much richer in recent decades is also true. The two are not a coincidence, there’s causality there. However, we hear often enough that it’s the residual control over industry by the government that drives that success. Sure, OK, so the bureaucracy doesn’t specify prices or detailed actions but the general guidance provided by a politically driven bureaucracy explains the outperformance.

Except it doesn’t. Those former state industries still enjoying that government guidance perform worse than the free market firms sadly lacking it. State planning is keeping China poorer than it need be, not aiding its growth.

The report he’s commenting on:

Changing the tiger’s stripes: Reform of Chinese state-owned enterprises in the penumbra of the state

Ann Harrison, Marshall W. Meyer, Will Wang, Linda Zhao, Minyuan Zhao 07 April 2019The conventional wisdom that privatisation of state-owned enterprises reduces their dependence on the state and yields positive economic benefits has not always been borne out by empirical work. Using a comprehensive dataset from China, this column shows that privatised SOEs continue to benefit from government support in the form of low-interest loans and subsidies relative to private enterprises that have never been state-owned. Although there are clear improvements in performance post-privatisation, privatised SOEs continue to significantly under-perform compared to private firms.

Much of China’s economic growth has been driven by the emergence of a vibrant private sector, today accounting for approximately 60% of GDP and 80% of employment. Conventional wisdom holds that privatisation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) reduces their dependence on the state and yields positive economic benefits including enhanced firm performance, productivity, and innovation. The pro-privatisation argument is that the state either cannot monitor managers properly or chooses not to pursue efficiency because state interests take precedence over financial results (Boardman and Vining 1989, Vickers and Yarrow 1991, Shleifer and Vishny 1994). Empirical work, however, has produced mixed results on privatisation. For example, DeWenter and Malatesta (2001) found that, among the 500 largest firms globally in 1975, 1985, and 1995, private enterprises had significantly lower costs and higher profits than SOEs. Yet, when they examined a sub-sample of privatised firms, they found inconsistent results – performance increased post-privatisation, while leverage and employment increased mainly pre-privatisation. Market returns from privatisation also differed across countries, positive in Hungary, Poland, and the UK but insignificant elsewhere.

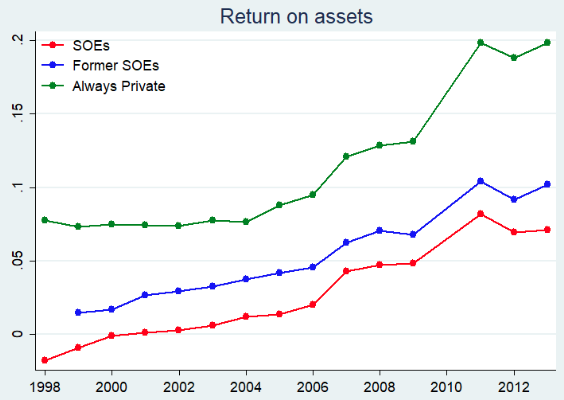

Our research on privatisation in China (Harrison et al. 2019) is unique in several respects. We analyse an extremely large sample of industrial firms, more than 3.5 million firm-years from 1998 to 2013, drawing on the Annual Industrial Survey conducted by the China National Bureau of Statistics. We compare privatised firms with firms that remained state-owned and firms that had never been state-owned. Most importantly, we compare both the performance and dependence on the state of privatised firms with firms having no prior state ownership. Overall, our results indicate selective performance gains from privatisation – privatised firms have greater productivity and are more likely to file patents than firms remaining state-owned even though their return on assets barely improves. The performance effects notwithstanding, privatised firms remain dependent on the state. Subsidies, concessionary interest rates, and loans granted to privatised firms remain at nearly the same levels as those to SOEs. Privatisation changes the behaviour of firms but not firms’ dependence on the state.

A graphical portrayal of the differing performance of the three types of Chinese companies from the report: