In the current issue of Reason, Mencken biographer Marion Elizabeth Rodgers explains why the great essayist would not welcome the adulation of the alt-right “Mencken Club”:

Libertarians and conservatives have always admired H. L. Mencken, the 20th century journalist and satirist famous for his literary and political commentary. Now the Baltimore author and editor, whose heydey lasted from the 1920s to the late 1940s, has become a hero to the alt-right, who have cherry-picked his views to support their white supremacist vision. For white nationalist leader Richard Spencer and fellow enthusiasts, Mencken embodies “worthy ideals,” namely, a questioning of “the egalitarian creed, democratic crusades, and welfare statism” that American democracy has become since the New Deal. Such is the essence of humor: It is hard to believe that Mencken would have ever given his worshippers the time of day.

[…]Unlike the Mencken Society — a scholarly organization founded in 1976 in Baltimore that hosts talks on Mencken’s life and works by such luminaries as the late Christopher Hitchens, Arnold Rampersad, and Alfred Kazin — the Mencken Club holds pseudo-academic conferences ranging in themes as “The West: Is It Dead Yet?” or “The Right Revisited.” In 2016, the club focused on the populism of Donald Trump and the preservation of white Christian heritage through anti-immigration policies. White House speechwriter Darren Beattie spoke to members alongside Peter Brimelow, white nationalist and founder of the anti-immigrant website Vdare.com — a gig that ultimately cost Beattie his job.

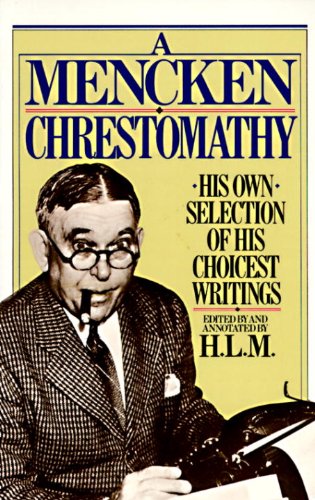

Speakers rarely mention Mencken’s name at their meetings, except for random recitals from Chrestomathy or his earliest works: The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1908), whom the alt-right see as a great visionary, and from Men Versus the Man: A Correspondence between Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H. L. Mencken, Individualist (1910), an epistolary debate where Mencken explores Social Darwinism, eugenics, heredity, and race. In the most offensive passage, Mencken defines “the American negro” as “a low-caste man,” and that the “superior white race will be fifty generations ahead of him.” In its podcast, club members touted Men Versus the Man as “a fun book” and asserted “race realists, anti-globalists, educational reductionists and immigration restrictionists can draw nourishment from Mencken … and his disdain for the low-caste man.”

In reality, Mencken would have shunned the white identity politics of the alt-right. To Mencken, Nietzsche’s “superior man” was the enlightened individual of honor and courage, regardless of race, creed, or social background. Soon after 1910, Mencken reversed his views of white superiority and began calling for civil rights for African Americans. Despite the fact that his Diary contains racial slurs and ethnic slang, Mencken rebelled against “the Aryan imbecilities of Hitler” and stated: “To me personally, race prejudice is one of the most preposterous of all the imbecilities of mankind. There are so few people on earth worth knowing that I hate to think of any man I like as a German or a Frenchman, a gentile or a Jew, Negro or a white man.”

He was especially contemptuous of white Anglo-Saxon Southerners, describing them as “shiftless [and] stupid,” and extolled African Americans as “superior to the whites against whom they are commonly pitted.” Unique for the mid-1900s and into the ’20s and ’30s, he collaborated with black intellectuals and was the first white editor to publish their work in his magazine, The American Mercury, and energetically promoted their writings in his books and columns and to his publisher Alfred Knopf. He was relentless in his campaigns against the Ku Klux Klan, and he joined forces with the NAACP to testify against lynching before the U.S. Congress. He repeatedly wrote against segregation; behind the scenes he discussed strategies with African-American leaders to promote civil rights.