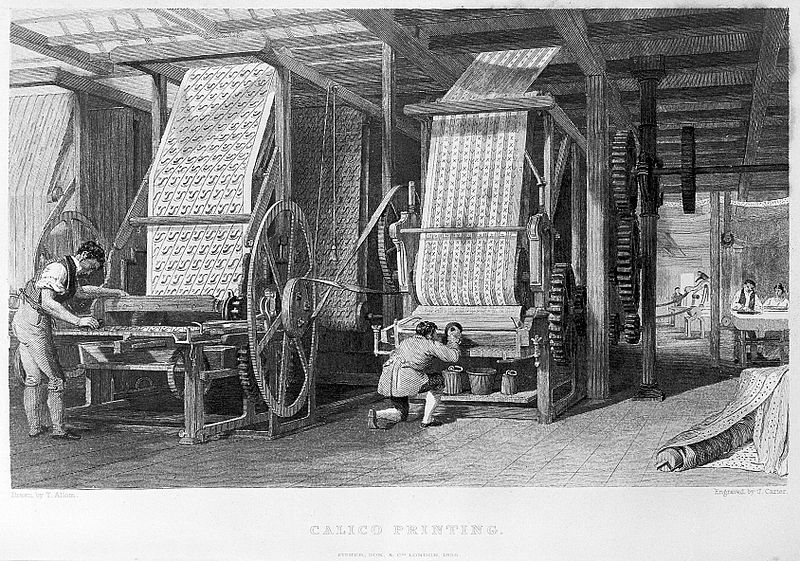

In the current issue of Reason, Virginia Postrel outlines an eighteenth-century French government attempt to prohibit calico cloth:

On a shopping trip to the butcher’s, young Miss la Genne wore her new, form-fitting jacket, a stylish cotton print with large brown flowers and red stripes on a white background. It got her arrested.

Another young woman stood in the door of her boss’ wine shop sporting a similar jacket with red flowers. She too was arrested. So were Madame de Ville, the lady Coulange, and Madame Boite. Through the windows of their homes, law enforcement authorities spotted these unlucky women in clothing with red flowers printed on white. They were busted for possession.

It was Paris in 1730, and the printed cotton fabrics known as toiles peintes or indiennes — in English, calicoes, chintzes, or muslins — had been illegal since 1686. It was an extreme version of trade protectionism, designed to shelter French textile producers from Indian cottons. Every few years the authorities would tweak the law, but the fashion refused to die.

Frustrated by rampant smuggling and ubiquitous scofflaws, in 1726 the government increased penalties for traffickers and anyone helping them. Offenders could be sentenced to years in galleys, with violent smugglers put to death. Local authorities were given the power to detain without trial anyone who merely wore the forbidden fabrics or upholstered furniture with them.

“The exasperation of the lawmakers, after forty years of successive edicts and ordinances which had been largely ignored, flouted or circumvented on a wholesale basis, can be sensed in this law,” writes the fashion historian Gillian Crosby in a 2015 dissertation on the ban. Her archival research shows a spike in arrests for simple possession. “Impotent at stopping the cross-border trade, printing or the peddling of goods,” she writes, “government officials concentrated on making an example of individual wearers, in an attempt to halt the fashion.”

They failed.

In the annals of prohibition, the French war on printed fabrics is one of the strangest, most futile, and most extreme chapters. It’s also one of the most intellectually consequential, producing many of the earliest arguments for economic liberalism. “Long before the more famous debates about the liberalisation of the grain trade, about taxation, or even about the monopoly of the French Indies Company, philosophes and Enlightenment political economists saw the calico debate as their first important battleground,” writes the historian Felicia Gottmann in Global Trade, Smuggling, and the Making of Economic Liberalism (Palgrave Macmillan).