Several months ago, the Washington Post reported on a new study of wealth and inequality that tracked how many billionaires got rich through competition in the market and how many got rich through political “connections”:

The researchers found that wealth inequality was growing over time: Wealth inequality increased in 17 of the 23 countries they measured between 1987 and 2002, and fell in only six, Bagchi says. They also found that their measure of wealth inequality corresponded with a negative effect on economic growth. In other words, the higher the proportion of billionaire wealth in a country, the slower that country’s growth. In contrast, they found that income inequality and poverty had little effect on growth.

The most fascinating finding came from the next step in their research, when they looked at the connection between wealth, growth and political connections.

The researchers argue that past studies have looked at the level of inequality in a country, but not why inequality occurs — whether it’s a product of structural inequality, like political power or racism, or simply a product of some people or companies faring better than others in the market. For example, Indonesia and the United Kingdom actually score similarly on a common measure of inequality called the Gini coefficient, say the authors. Yet clearly the political and business environments in those countries are very different.

So Bagchi and Svejnar carefully went through the lists of all the Forbes billionaires, and divided them into those who had acquired their wealth due to political connections, and those who had not. This is kind of a slippery slope — almost all billionaires have probably benefited from government connections at one time or another. But the researchers used a very conservative standard for classifying people as politically connected, only assigning billionaires to this group when it was clear that their wealth was a product of government connections. Just benefiting from a government that was pro-business, like those in Singapore and Hong Kong, wasn’t enough. Rather, the researchers were looking for a situation like Indonesia under Suharto, where political connections were usually needed to secure import licenses, or Russia in the mid-1990s, when some state employees made fortunes overnight as the state privatized assets.

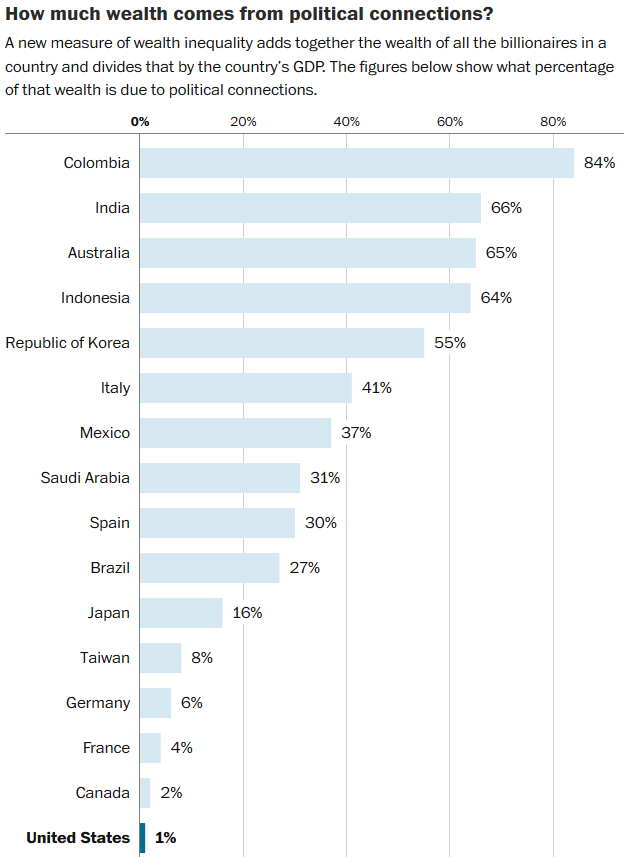

The researchers found that some countries had a much higher proportion of billionaire wealth that was due to political connections than others did. As the graph below, which ranks only countries that appeared in all four of the Forbes billionaire lists they analyzed, shows, Colombia, India, Australia and Indonesia ranked high on the list, while the U.S. and U.K. ranked very low.

Looking at all the data, the researchers found that Russia, Argentina, Colombia, Malaysia, India, Australia, Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea and Italy had relatively more politically connected wealth. Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.K. all had zero politically connected billionaires. The U.S. also had very low levels of politically connected wealth inequality, falling just outside the top 10 at number 11.

When the researchers compared these figures to economic growth, the findings were clear: These politically connected billionaires weighed on economic growth. In fact, wealth inequality that came from political connections was responsible for nearly all the negative effect on economic growth that the researchers had observed from wealth inequality overall. Wealth inequality that wasn’t due to political connections, income inequality and poverty all had little effect on growth.

Back in 2000, the Sunday Times of London compiled a list of the 200 richest Britons since 1066. The number of people who got on the list through government corruption was very high. Throw in people who were hereditary aristocrats and that was just about the whole 200. There were two or three people who got on the list through hard work and brains. Josiah Wedgewood is the only one whose name I remember.

Comment by Steve Muhlberger — November 28, 2015 @ 11:39

That’s in no way surprising … you couldn’t be really wealthy between 1066 and the early 1700s without being a nob (er, no disrespect, Your Grace). I assume the list excluded the Jewish bankers and merchants who were almost certainly in the 1% of the population before being thrown out of the kingdom for some 300 years.

Comment by Nicholas — November 28, 2015 @ 12:00