Published on 21 May 2015

The big success of the Gallipoli Campaign never came, thousands of soldiers died and so Winston Churchill is forced to resign. At the same time August von Mackensen is pushing back the Russians and forcing them to hide in Przemyśl fortress – the same fortress they just conquered from the Austro-Hungarians a few weeks earlier.

May 22, 2015

Przemyśl Falls Again – Winston Churchill Gets Fired I THE GREAT WAR Week 43

Reconstructing history – a population explosion in ancient Greece?

Anton Howes deserves what he gets for a blog post he titled “Highway to Hellas: avoiding the Malthusian trap in Ancient Greece”:

There’s a fantastic post by Pseudoerasmus examining the supposed ‘efflorescence’ of economic growth in Ancient Greece, and some of the causal hypotheses put forward by Josiah Ober in an upcoming book (which I’m very much looking forward to reading in full). Suffice to say, the data estimates used by Ober raise more questions than they answer.

If the constructed data is correct, then not only did Greek population grow by an extraordinary amount during the Archaic Period roughly 800-500 BC, but Greek consumption per capita grew by 50-100% from 800-300 BC. As Pseudoerasmus points out, this would imply a massive productivity gain of some 450-1000%, or 0.3-0.46% growth per annum.

This seems quite implausible to me. Indeed, the population estimates imply that the Ancient Greek population would have been substantially larger than that of Greece in the 1890s AD, along with higher agricultural productivity! This is all the more puzzling as there appears to have been no major technological change to support so many more mouths to feed, let alone feed them better than before.

But assuming the data are correct, what would have to give? Pseudoerasmus explores a number of different possibilities, such as the gains from integrating trade across the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea; or that the Greeks might have shifted agricultural production to cash crops like wine and oil and imported grain instead. None of these quite seem good enough for such a massive and prolonged escape from the Malthusian pressures of population outstripping the productivity of agriculture (although I hope the so-far unavailable chapters from Ober’s book might shed some more light on this).

A remaining explanation offered by Pseudoerasmus may, however, be the winner: that Greeks weren’t using land more intensively as Ober seems to suggest, but rather expanding the land that they brought under cultivation by colonising new areas.

Al Stewart – “Trains”

Published on 19 Mar 2013

In the sapling years of the post-war world in an English market town

I do believe we travelled in schoolboy blue, the cap upon the crown

Books on knee; our faces pressed against the dusty railway carriage panes

As all our lives went rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsThe school years passed like eternity and at last were left behind

And it seemed the city was calling me to see what I might find

Almost grown, I stood before horizons made of dreams

I think I stole a kiss or two, while rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

All our lives were a whistle stop affair; no ties or chains

Throwing words like fireworks in the air, not much remains

A photograph in your memory, through the colored lens of time

All our lives were just a smudge of smoke against the skyThe silver rails spread far and wide through the nineteenth century

Some straight and true, some serpentine, from the cities to the sea

And out of sight of those who rode in style, there worked the military mind

On through the night to plot and chart the twisting paths of trainsOn the day they buried Jean Jaures, World War One broke free

Like an angry river overflowing its banks impatiently

While mile on mile the soldiers filled the railway stations’ arteries and veins

I see them now go laughing on the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

Rolling off to the front across the narrow Russian gauge

Weeks turn into months and the enthusiasm wanes

Sacrifices in seas of mud, and still you don’t know why

All their lives are just a puff of smoke against the skyThen came surrender; then came the peace

Then revolution out of the east

Then came the crash; then came the tears

Then came the thirties, the nightmare years

Then came the same thing over again

Mad as the moon, that watches over the plain

Oh, driven insaneBut oh, what kind of trains are these, that I never saw before

Snatching up the refugees from the ghettoes of the war

To stand confused, with all their worldly goods, beneath the watching guards’ disdain

As young and old go rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsAnd the driver only does this job with vodka in his coat

And he turns around and he makes a sign with his hand across his throat

For days on end, through sun and snow, the destination still remains the same

For those who ride with death above the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

What became of the innocence they had in childhood games

Painted red or blue, when I was young they all had names

Who’ll remember the ones who only rode in them to die

All their lives are just a smudge of smoke against the skyNow forty years have come and gone and I’m far away from there

And I ride the Amtrak from New York City to Philadelphia

And there’s a man to bring you food and drink

And sometimes passengers exchange a smile or two rolling on the humming wheels

But I can’t tell you if it’s them or if it’s only me

But I believe when they look outside they don’t see what I see

Over there, beyond the trees, it seems that I can just make out the stained

Fields of Poland calling out to all the passing trainsTrains…

I suppose that there’s nothing in this life remains the same

Everything is governed by the losses and the gains

Still sometimes I get caught up in the past, I can’t say why

All our lives are just a smudge of smoke, or just a breath of wind against the sky

The trains of war – the military application of steam power

James Simpson on the revolution in military affairs triggered by the development of the steam engine and the railways:

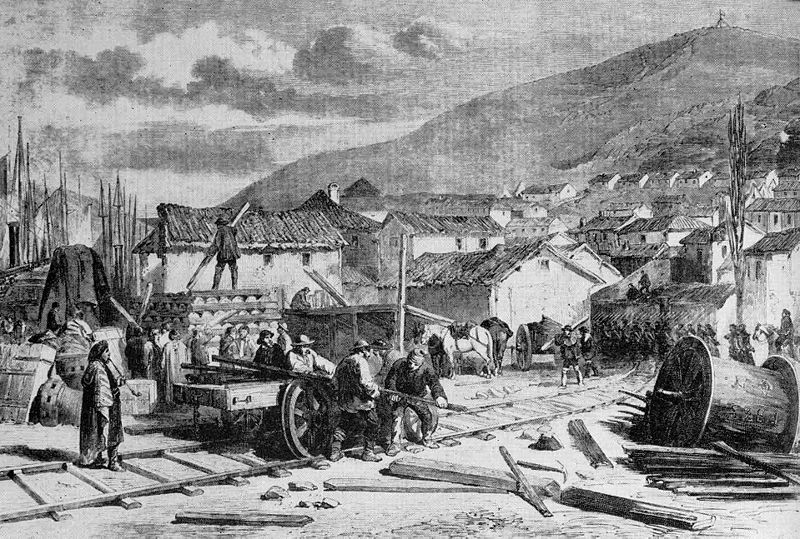

Navvies working on the Grand Crimean Central Railway, 1854. Charles Walker: Thomas Brassey, Railway Builder, 1969. (via Wikipedia)

Trains were cutting-edge weapons of war in the 19th century — and all the major powers were figuring out how to deploy them. The Europeans learned how to move troops by train. The Americans — how to fight on rail cars. The British, meanwhile, found they could dominate an empire from the tracks.

In today’s world of tanks, bombers and submarines, it’s perhaps hard to believe that the train was once an amazingly mobile weapons platform. They might be locked to their rails, but for over a century trains were the fastest means of hauling troops and artillery to front lines across the world.

The invention of the railway shaped warfare for a century. Rails allowed force projection across immense distances — and at speeds which were impossible on foot or by horse.

[…]

The first demonstration of the military efficacy of the railroads was the 1846 Polish Uprising. Prussia rushed 12,000 troops of the Sixth Army Corps, with guns and horses, to the Free City of Krakow to help put down the Polish rebellion. In this period of nationalist uprisings, Russia and Austria also used their railroads against similar uprisings from 1848 to 1850.

A lack of infrastructure and experience stifled the success of these early endeavors. Due to a lack of rolling stock, suitable platforms and double-track stretches, the trains sometimes operated far slower than a man could march on foot.

Austria was first to get it right. In 1851, the Austrian Empire shuttled 145,000 men, nearly 2,000 horses, 48 artillery pieces and 464 vehicles over 187 miles.