Published on 26 Jan 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, also known as the Lion of Africa, was commander of the German colonial troops in German East Africa during World War 1. His guerilla tactics used againd several world powers of the time are considered to be one of the most successful military missions of the whole war. In Germany, he was celebrated as a hero until recently. But recent historical research show a picture much more controversial than the one of a glorious hero.

January 28, 2015

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Employment skills at the very basic level

Warren Meyer says what the US needs to do is to make changes to the structure of the working world to allow companies to profitably hire low-skilled workers:

A lot of head scratching goes on as to why, when the income premium is so high for gaining skills, there are not more people seeking to gain them. School systems are often blamed, which is fair in part (if I were to be given a second magic wand to wave, it would be to break up the senescent government school monopoly with some kind of school choice system). But a large portion of the population apparently does not take advantage of the educational opportunities that do exist. Why is that?

When one says “job skills,” people often think of things like programming machine tools or writing Java code. But for new or unskilled workers — the very workers we worry are trapped in poverty in our cities — even basic things we take for granted like showing up on-time reliably and working as a team with others represent skills that have to be learned. Amazon.com CEO Jeff Bezos, despite his Princeton education, still learned many of his first real-world job skills working at McDonald’s. In fact, back in the 1970’s, a survey found that 10% of Fortune 500 CEO’s had their first work experience at McDonald’s.

Part of what we call “the cycle of poverty” is due not just to a lack of skills, but to a lack of understanding of or appreciation for such skills that can cross generations. Children of parents with few skills or little education can go on to achieve great things — that is the American dream after all. But in most of these cases, kids who are successful have parents who were, if not educated, at least knowledgeable about the importance of education, reliability, and teamwork — understanding they often gained via what we call unskilled work. The experience gained from unskilled work is a bridge to future success, both in this generation and the next.

But this road to success breaks down without that initial unskilled job. Without a first, relatively simple job it is almost impossible to gain more sophisticated and lucrative work. And kids with parents who have little or no experience working are more likely to inherit their parent’s cynicism about the lack of opportunity than they are to get any push to do well in school, to work hard, or to learn to cooperate with others.

Unfortunately, there seem to be fewer and fewer opportunities for unskilled workers to find a job. As I mentioned earlier, economists scratch their heads and wonder why there are not more skilled workers despite high rewards for gaining such skills. I am not an economist, I am a business school grad. We don’t worry about explaining structural imbalances so much as look for the profitable opportunities they might present. So a question we business folks might ask instead is: If there are so many under-employed unskilled workers rattling around in the economy, why aren’t entrepreneurs crafting business models to exploit this fact?

The great and the good gather at Davos

And Monty calls ’em exactly what they are:

Luckily, all is not lost. Our moral and ethical betters have gathered in Davos to light their cigars with hundred-dollar bills while mocking the tubercular bootblack who’s been pressed into service to keep their shoes looking spiffy while they chat and laugh and eat lobster canapes. Oh, wait, I read that wrong, sorry. They’re in Davos to discuss the pressing problem of Global Warming(tm). Because they’re so concerned about Global Warming(tm) that they felt compelled to fly their private jets to an upscale enclave in the Swiss Alps to talk about it. While making fun of the tubercular bootblack who’s spit-shining their wingtips.

Don’t get me wrong – I’m a big believer in ostentatious displays of wealth. If I had the money, I’d build a hundred-foot-high statue of myself made out of pure platinum and then hire homeless people to worship at it for no fewer than eight hours per day. (I’d pay them a fair wage, though. What’s the going rate for abject obeisance to a living God? I’ll have to look it up.) But this Davos thing is just…rank. It’s a collection of rich fart-sniffers who want to congratulate each other on how socially conscious they are, and how much they care about the Little People. (Except the tubercular bootblack, whom they often kick with their rich-guy shoes.)

Spending more money on education won’t guarantee better outcomes for students

Not having gone to university myself, I can’t speak from direct personal experience, but my strong sense is that the university degree today fulfils almost exactly the role for job-seekers that a high school diploma did about a generation ago. Most of the “entry level” jobs that actually offer some sort of career progression require no more skill or preparation now than they did 25 or 30 years ago … but the combination of lowered standards in secondary school and the vast expansion of post-secondary education have encouraged employers to filter job applicants for such openings by education first. As a direct result, parents have been pushing their children toward university as the only way to ensure those kids have a fighting chance to get into jobs that might, eventually, lead somewhere both interesting and remunerative.

But with more demand for places at university, the government is under pressure to provide funding — both to the universities to create more spaces, and to the students themselves to allow them to pay their tuition and other costs. Megan McArdle worries that pouring more money into the system isn’t the right answer:

The other day, I argued that maybe we should rethink our current policy of endlessly dumping more money into college education. It’s completely true that there is a big wage premium for having a college degree — but it does not therefore follow that we will make everyone better off by trying to shove every American through post-secondary (aka tertiary) education. We may simply be setting up college as a substitute for a high school diploma: a signal to employers that you can read and write, and are able to turn in scheduled assignments within a reasonable time frame. And in the process, excluding people who aren’t college-educated from access to decent jobs.

Predictably, this was not met with shouts of joy and universal admiration in all quarters. I was accused of just wanting to stick it to President Barack Obama, and also of wishing to deny the dream of college education that should be the birthright of every single American. I was also accused of being unfamiliar with the known fact that America woefully underinvests in education compared to other advanced nations.

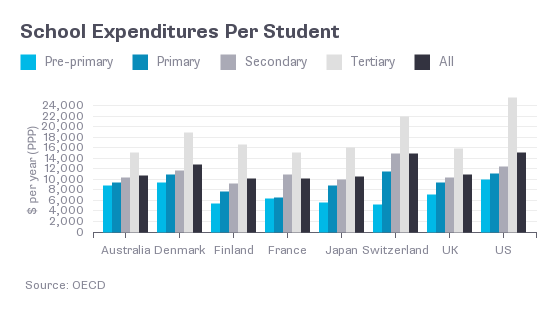

It is true that I am unfamiliar with America’s woeful underinvestment in education, in the same way that I am unfamiliar with the tooth fairy, because both are legends with no basis in fact. American spending on education is in line with that of our peers in the developed world — a little higher than some, a little lower than others, but not really remarkable either way:

[…]

You can argue that there’s an inequality problem in our schools. In fact, I think there is obviously an inequality problem in our schools, but that the big problem is not at the college level, but rather in the primary and secondary schools that are overwhelmingly government-funded. And those disparities are also not primarily about the dollar amounts going into schools — Detroit spends well above the U.S. average per pupil, and yet one study found that half the population of the city was “functionally illiterate.”

Should we fix the issues with those schools? Absolutely — and doing so might mean spending more money. But that doesn’t mean that we need to increase the overall level of educational funding. It means that we need to identify ways to improve those underperforming schools, then find out how much more it would cost to implement those programs. It is just as likely that improvements will come from changing methods and reallocating resources as that they will require us to pour more money into failing institutions.

QotD: The libertarian movement

The libertarian or “freedom movement” is a loose and baggy monster that includes the Libertarian Party; Ron Paul fans of all ages; Reason magazine subscribers; glad-handers at Cato Institute’s free-lunch events in D.C.; Ayn Rand obsessives and Robert Heinlein buffs; the curmudgeons at Antiwar.com; most of the economics department at George Mason University and up to about one-third of all Nobel Prize winners in economics; the beautiful mad dreamers at The Free State Project; and many others. As with all movements, there’s never a single nerve center or brain that controls everything. There’s an endless amount of in-fighting among factions […] On issues such as economic regulation, public spending, and taxes, libertarians tend to roll with the conservative right. On other issues — such as civil liberties, gay marriage, and drug legalization, we find more common ground with the progressive left.

Nick Gillespie, “Libertarianism 3.0; Koch And A Smile”, The Daily Beast, 2014-05-30.