In a post from earlier this year, Scott Alexander discusses a common example of what has been described as a “motte-and-bailey” argument:

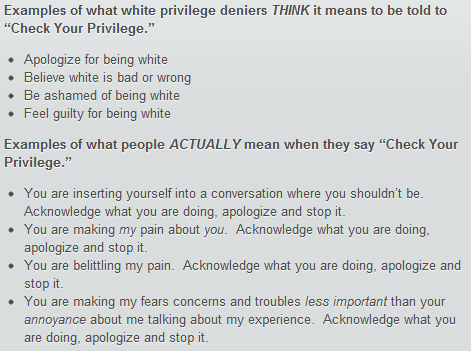

I recently learned there is a term for the thing social justice does. But first, a png from racism school dot tumblr dot com.

So, it turns out that privilege gets used perfectly reasonably. All it means is that you’re interjecting yourself into other people’s conversations and demanding their pain be about you. I think I speak for all straight white men when I say that sounds really bad and if I was doing it I’m sorry and will try to avoid ever doing it again. Problem solved, right? Can’t believe that took us however many centuries to sort out.

A sinking feeling tells me it probably isn’t that easy.

In the comments section of the last disaster of a social justice post on my blog, someone started talking about how much they hated the term “mansplaining”, and someone else popped in to — ironically — explain what “mansplaining” was and why it was a valuable concept that couldn’t be dismissed so easily. Their explanation was lucid and reasonable. At this point I jumped in and commented:

I feel like every single term in social justice terminology has a totally unobjectionable and obviously important meaning — and then is actually used a completely different way.

The closest analogy I can think of is those religious people who say “God is just another word for the order and beauty in the Universe” — and then later pray to God to smite their enemies. And if you criticize them for doing the latter, they say “But God just means there is order and beauty in the universe, surely you’re not objecting to that?”

The result is that people can accuse people of “privilege” or “mansplaining” no matter what they do, and then when people criticize the concept of “privilege” they retreat back to “but ‘privilege’ just means you’re interrupting women in a women-only safe space. Surely no one can object to criticizing people who do that?”

…even though I get accused of “privilege” for writing things on my blog, even though there’s no possible way that could be “interrupting” or “in a women only safe space”.

When you bring this up, people just deny they’re doing it and call you paranoid.

When you record examples of yourself and others getting accused of privilege or mansplaining, and show people the list, and point out that exactly zero percent of them are anything remotely related to “interrupting women in a women-only safe space” and one hundred percent are “making a correct argument that somebody wants to shut down”, then your interlocutor can just say “You’re deliberately only engaging with straw-man feminists who don’t represent the strongest part of the movement, you can’t hold me responsible for what they do” and continue to insist that anyone who is upset by the uses of the word “privilege” just doesn’t understand that it’s wrong to interrupt women in safe spaces.

I have yet to find a good way around this tactic.

My suspicion about the gif from racism school dot tumblr dot com is that the statements on the top show the ways the majority of people will encounter “privilege” actually being used, and the statements on the bottom show the uncontroversial truisms that people will defensively claim “privilege” means if anyone calls them on it or challenges them. As such it should be taken as a sort of weird Rosetta Stone of social justicing, and I can only hope that similarly illustrative explanations are made of other equally charged terms.

H/T to Sam Bowman for the link.