Over the last few days, I’ve posted some entries on the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three). We’re still sorting out the end of Otto von Bismarck’s grand diplomatic juggling act, and we’ve barely dug into the fascinating ethnic, religious, cultural, and linguistic goulash of the Balkans.

France searches for allies

After the disaster of the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second Empire, France was left (for the second time) alone and friendless on the European stage. Having painfully rebuilt from the end of the Napoleonic wars, France faced the need to do it all again, but now with a newly unified and powerful enemy literally on the Eastern frontier.

The overriding foreign policy objectives of the Third Republic were finding ways to counteract the German Reich … even if it meant cosying up to the most autocratic regime in Europe. With Bismarck off the scene, the French were able to further pursue a dialogue with the Tsar’s government that actually began with financial aid from Paris in 1888 leading eventually to a formal alliance in 1892. The loans were intended to allow Russia to improve existing East-West railways and to build new ones with the purpose of allowing Russian troops to be more quickly concentrated on the German-Russian and (less urgently) Austrian-Russian borders. Russia had the military manpower while France had the financial means and technological know-how — both parties drew benefits from the deal (but the French needed the Russians more than vice-versa).

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan shows that the Russians were aware of the imbalance in the needs of the allies and resented the French attitude to them:

Although the French alliance had caused difficulties initially, Russian opinion had largely come around to seeing it as a good thing, a neat matching of Russian manpower with French money and technology. Of course, there were strains over the years. France tried to use its financial leverage over Russia to shape Russian military planning to meet French needs or to insist that Russia place its orders for new weapons with French firms. The Russians resented this “blackmail”, as they sometimes called it, which was demeaning to Russia as a great power. As Vladimir Kokovtsov, Russia’s Minister of Finance for much of the decade before 1914, complained: “Russia is not Turkey; our allies should not set us an ultimatum, we can get by without these direct demands.”

The French also put pressure on Russia to avoid confrontations with Britain, as French and British diplomats had started working toward some kind of understanding, and the French felt (with some justice) that the Russians might easily do damage to that process by some mild adventurism on a distant frontier with Britain’s colonies.

Britain’s global-scale worries

Britain’s lack of direct engagement during much of the period of the Concert of Europe was rational: British interests lay away from Europe, with the burgeoning colonies providing more than enough economic, diplomatic, and military activity for British tastes. From British Imperial viewpoints, the Germans were a mere distraction — it was the Russians who seemed to be threatening the Empire at every turn.

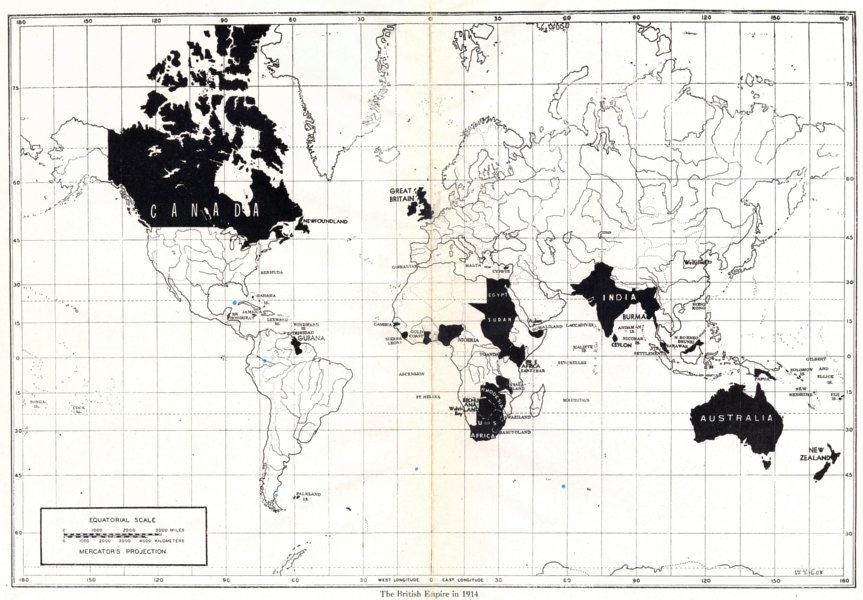

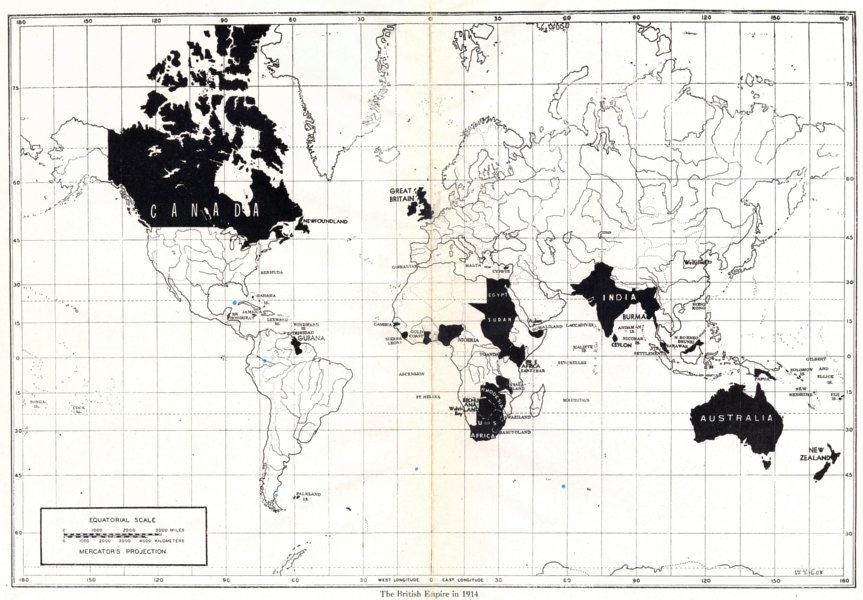

The British Empire in 1914 (via antiquaprintgallery.com)

Margaret MacMillan writes that before the popular series of sensationalist novels by William Le Queux featured German invasions of Britain, his chosen villains were the Russians:

In Britain itself, public opinion was strongly anti-Russian. In popular literature, Russia was exotic and terrifying: the land of snow and golden domes, of wolves chasing sleighs through the dark forests, of Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great. Before he made Germany the enemy in his novels, the prolific William Le Queux used Russia. In his 1894 The Great War in England in 1897, Britain was invaded by a combined French and Russian force but the Russians were by far the more brutal. British homes were burned, innocent civilians shot and babies bayoneted. “The soldiers of the Tsar, savage and inhuman, showed no mercy to the weak and unprotected. They jeered and laughed at piteous appeal, and with fiendish brutality enjoyed the destruction which everywhere they wrought.”

In Britain itself, public opinion was strongly anti-Russian. In popular literature, Russia was exotic and terrifying: the land of snow and golden domes, of wolves chasing sleighs through the dark forests, of Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great. Before he made Germany the enemy in his novels, the prolific William Le Queux used Russia. In his 1894 The Great War in England in 1897, Britain was invaded by a combined French and Russian force but the Russians were by far the more brutal. British homes were burned, innocent civilians shot and babies bayoneted. “The soldiers of the Tsar, savage and inhuman, showed no mercy to the weak and unprotected. They jeered and laughed at piteous appeal, and with fiendish brutality enjoyed the destruction which everywhere they wrought.”

Aside from the role of barbarous invaders in popular fiction, there were sufficient things to offend British consciences which added to this general dislike of the Russian state:

Radicals, liberals and socialists all had many reasons to hate the regime with its secret police, censorship, lack of basic human rights, its persecution of its opponents, its crushing of ethnic minorities and its appalling record of anti-Semitism. Imperialists on the other hand hated Russia because it was a rival to the British Empire. Britain could never come to an agreement with Russia in Asia, said Curzon, who had been Salisbury’s Under-secretary at the Foreign Office before he became Viceroy in India. Russia was bound to keep expanding as long as it could get away with it. In any case the “ingrained duplicity” of Russian diplomats made negotiations futile.

In the wake of the abortive 1905 revolution, it was easy to think of Russia as being weak and unstable, but as economic growth slowly returned, the government’s efforts to extend its control over far-flung recently acquired territories led to roads and railways being built … which Britain could hardly help but view as being at least partly military in nature:

It was one of the rare occasions on which [Curzon] agreed with the chief of the Indian general staff, Lord Kitchener, who was demanding more resources from London to deal with “the menacing advance of Russia towards our frontiers.” What particularly worried the British were the new Russian railways, either built or planned, which stretched down to the borders of Afghanistan and Persia and which now made it possible for the Russians to bring more force to bear. Although the term was not to be coined for another eighty years, the British were also becoming acutely aware of what Paul Kennedy called “imperial overstretch”. As the War Office said in 1907, the expanded Russian railway system would make the military burden of defending India and the empire so great that “short of recasting our whole military system, it will become a question of practical politics whether or not it is worth our while to retain India.”

More to follow over the next few days. This series of blog posts has certainly ballooned past what I originally thought would be required (and I’m skipping over masses and masses of stuff already). This just reinforces my earlier point that the situation was far more complex 100 years ago than we might think.