January 1, 2015

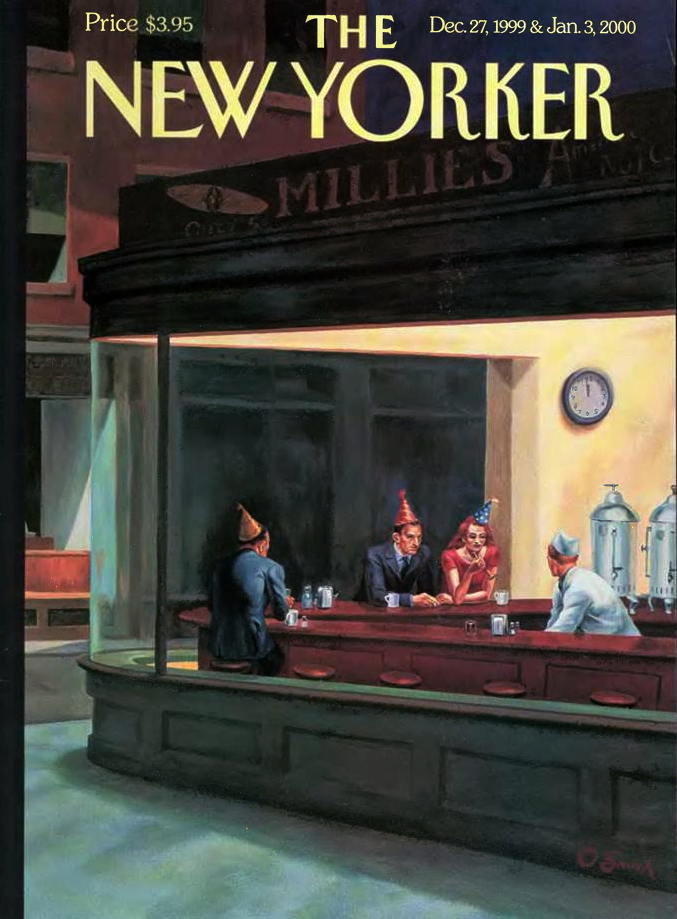

Oh, yeah … Happy New Year (with apologies to Edward Hopper)

The Laffer Curve at 40

In the Washington Post, Stephen Moore recounts the tale of the most famous napkin in US economic history:

It was 40 years ago this month that two of President Gerald Ford’s top White House advisers, Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfeld, gathered for a steak dinner at the Two Continents restaurant in Washington with Wall Street Journal editorial writer Jude Wanniski and Arthur Laffer, former chief economist at the Office of Management and Budget. The United States was in the grip of a gut-wrenching recession, and Laffer lectured to his dinner companions that the federal government’s 70 percent marginal tax rates were an economic toll booth slowing growth to a crawl.

To punctuate his point, he grabbed a pen and a cloth cocktail napkin and drew a chart showing that when tax rates get too high, they penalize work and investment and can actually lead to revenue losses for the government. Four years later, that napkin became immortalized as “the Laffer Curve” in an article Wanniski wrote for the Public Interest magazine. (Wanniski would later grouse only half-jokingly that he should have called it the Wanniski Curve.)

This was the first real post-World War II intellectual challenge to the reigning orthodoxy of Keynesian economics, which preached that when the economy is growing too slowly, the government should stimulate demand for products with surges in spending. The Laffer model countered that the primary problem is rarely demand — after all, poor nations have plenty of demand — but rather the impediments, in the form of heavy taxes and regulatory burdens, to producing goods and services.

[…]

Solid supporting evidence came during the Reagan years. President Ronald Reagan adopted the Laffer Curve message, telling Americans that when 70 to 80 cents of an extra dollar earned goes to the government, it’s understandable that people wonder: Why keep working? He recalled that as an actor in Hollywood, he would stop making movies in a given year once he hit Uncle Sam’s confiscatory tax rates.

When Reagan left the White House in 1989, the highest tax rate had been slashed from 70 percent in 1981 to 28 percent. (Even liberal senators such as Ted Kennedy and Howard Metzenbaum voted for those low rates.) And contrary to the claims of voodoo, the government’s budget numbers show that tax receipts expanded from $517 billion in 1980 to $909 billion in 1988 — close to a 75 percent change (25 percent after inflation). Economist Larry Lindsey has documented from IRS data that tax collections from the rich surged much faster than that.

Unintended consequences – charities suffer due to US anti-terror measures

It’s actually rather amazing how powerful the US government can be … and we’re not talking about military power here. US banking laws are being exported to other nations without their consent or consultation, and there’s nothing non-US governments can do about it:

Now here’s a real surprise. The various anti-terror laws, terrorist financing laws, know your customer, illicit money tracking laws which now festoon the financial system have costs. Really, who would have thought it that bureaucratic regulations have real costs out there in the real world? It’s something of an amusement that it’s a rather lefty think tank, Demos, that brings us this news. For, of course, it tends to be those who are rather lefty who tell us that regulation is the cure for all our ills and no, of course not, regulations never have any costs they only do good things. You know, the Elizabeth Warren approach, piles of regulations on finance will be just wonderful, no one will ever lose out.

It particularly interests me as I’ve a very vague connection with a charity, Interpal, that has been hit by these sorts of regulations. Not, I hasten to add, that I am actually connected with that charity, only that I was once on a TV program with the head of it discussing their difficulties in gaining access to a bank account. The basic problem was that the Americans thought that they were less than kosher (the charity themselves obviously disagree) and that thus they shouldn’t have access to the banking system. This shouldn’t be all that much of a problem as they’re a UK charity and they were looking for access to the UK banking system. But that isn’t how it all works. If the Americans decide that they don’t think someone should have access to the banking system then they tell the bank that, well, you wouldn’t want us to come looking at your American banking licence if you were to offer an account with your UK licence, would you? And thus there is the leverage required to extend US law to other countries.

[…]

It’s not particularly the British government that is causing these problems although they have a part in it, to be sure. It’s the general international rules over who a bank may deal with, what they’ve got to know about them and what they’re doing with the money. Everyone seems quite happy with this as it stops (or hinders at least) drug dealing, money laundering and tax abuse. But it does have costs. Absolutely any set of regulations will affect people who are not the target of said regulations. If you insist that banks make a large effort to understand what their customers are doing then the banks will simply reject some customers as not being worth the candle. If perhaps handling money for some Islamic terrorist means bankers go to jail then bankers won’t handle the money of anyone who might be an Islamic terrorist: nor anyone who wanders around in Huddersfield in Islamic robes and states that they’re raising money to help the poor of Gaza. The manager of, say, Lloyds Bank in Huddersfield doesn’t know what the heck is going on in Gaza, who is linked to Hamas, who is not, who is delivering food and who is doing other less reputable things. And there’s no reason why she should either. So, the laws to prevent the one will lead to the other not gaining access to a bank account. This is really simple, simple, stuff.

This is what happens when people regulate.

J.R.R. Tolkien – confessed anarchist

In The Federalist, Jonathan Witt and Jay W. Richards wonder if the Shire is a hippie paradise:

“The Battle of the Five Armies,” the final installment of The Hobbit film trilogy, opened last week, and online boards are buzzing with discussions of Peter Jackson’s casting decisions, his use or overuse of computer-generated imagery and what Middle-Earth’s creator, J.R.R. Tolkien, would have thought of the films. Geeky questions, to be sure, but for those who follow both Tolkien and politics, we suggest a still geekier line of inquiry: How would Tolkien vote? That is, what kind of political vision did the Oxford professor carry into his novels?

His wildly popular novels have, after all, shaped generations of followers, and are shot through with valuable insights about man and government that might not be obvious to a casual reader or fan of the movie versions. Tolkien’s political insights, moreover, are in danger of being lost and forgotten in the capitols of the West. Here, in other words, is a vein worth mining.

[…]

An early hint of this can be found in the beloved homeland of the hobbits, the Shire. Her pastoral villages have no department of unmotorized vehicles, no internal revenue service, no government official telling people who may and may not have laying hens in their backyards, no government schools lining up hobbit children in geometric rows to teach regimented behavior and groupthink, no government-controlled currency, and no political institution even capable of collecting tariffs on foreign goods.

“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government,’” we eventually learn. “Families for the most part managed their own affairs.”

Significantly, Tolkien once described himself as a hobbit “in all but size,” commenting in the same letter that his “political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs).” As he explained, “The most improper job of any man, even saints, is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.”

In the Shire, Tolkien created a society after his own heart, one marked by minimal government, private charity, and a commitment to property rights and the rule of law.

This isn’t to say the Shire is without problems. Near the end of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo returns home after a quest to destroy a corrupting ring of absolute power. To his dismay, a gang of bossy outsiders has infiltrated the Shire, “gatherers and sharers … going around counting and measuring and taking off to storage,” supposedly “for fair distribution,” but what becomes of most of it is anyone’s guess.

Ugly new buildings are being thrown up, beautiful hobbit homes spoiled. And for all the effort to “spread the wealth around” (to borrow a phrase from our current president), the only thing that seems to be spreading is the gatherers’ power. It’s a critique of aesthetically impoverished urban development, to be sure. But conservatives and progressives alike also have seen in it a pointed critique of the modern, hyper-regulated nanny state.

As Hal Colebatch put it in the Tolkien Encyclopedia, the Shire’s joyless regime of bureaucratic rules and suffocating redistribution “owed much to the drabness, bleakness and bureaucratic regulation of postwar Britain under the Attlee labor Government.”

It’s. Just. Wrong. Period.

Jacob Sullum on the always-hot-button topic of state torture:

In an interview on Sunday, NBC’s Chuck Todd asked former Vice President Dick Cheney if he was “OK” with the fact that a quarter of the suspected terrorists held in secret CIA prisons during the Bush administration “turned out to be innocent.” Todd noted that one of those mistakenly detained men died of hypothermia after being doused with water and left chained to a concrete wall, naked from the waist down, in a cell as cold as a meat locker.

Cheney replied that the end — to “get the guys who did 9/11” and “avoid another attack against the United States” — justified the means. “I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective,” he said.

Charles Fried, a Harvard law professor who served as solicitor general during the Reagan administration, and his son Gregory, a philosophy professor at Suffolk University, offer a bracing alternative to Cheney’s creepy consequentialism in their 2010 book Because It Is Wrong. They argue that torture is wrong not just when it is inflicted on innocents, and not just when it fails to produce lifesaving information, but always and everywhere.

That claim is bolder than it may seem. As the Frieds note, most commentators “make an exception for grave emergencies,” as in “the so-called ticking-bomb scenario,” where torturing a terrorist is the only way to prevent an imminent explosion that will kill many people. “These arguments try to have it both ways,” they write. “Torture is never justified, but then in some cases it might be justified after all.” The contradiction is reconciled “by supposing that the justifying circumstances will never come up.”

QotD: Henry Ford and the doubled wages – the real story

In 1913, turnover reached an unbelievable 370 percent, and Ford hired more than 50,000 people to maintain an average labor force of about 13,600. When profits swelled, he paid well for labor, creating an uproar when he doubled the basic wage to $5.00 a day, which triggered a virtual stampede of job seekers. Paying higher wages for labor was not altruistic in Ford’s eyes. Moreover, it wasn’t simply that Ford was trying to pay his workers “enough to buy back the product,” although he did preach a high-wage doctrine after the stock market crash in 1929. Rather, paying relatively high wages was, for Ford, a matter of smart business. He regarded well-paid skilled workers as important as high-grade material. By paying workers well, he effectively lowered his costs because higher wages reduced turnover and the need for constant training of new hires. (At the time, the newspapers saw Ford’s wage increase as an extraordinary gesture of goodwill.)

Mark Spitznagel, The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World, 2013.