As reported the other day, what was once the world’s fourth largest lake, the Aral Sea, has almost completely dried up due to Soviet water diversion projects of the late 1950s and early 1960s:

In the early 1960s, the Soviet government decided the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the east, would be diverted to irrigate the desert, in an attempt to grow rice, melons, cereals, and cotton.

This was part of the Soviet plan for cotton, or “white gold”, to become a major export. This temporarily succeeded, and in 1988, Uzbekistan was the world’s largest exporter of cotton.

The Soviet government made a deliberate choice to sacrifice the Aral Sea to create a vast new cotton-growing region in Uzbekistan. It was clearly quite successful, depending on how you choose to measure success.

The disappearance of the lake was no surprise to the Soviets; they expected it to happen long before. As early as 1964, Aleksandr Asarin at the Hydroproject Institute pointed out that the lake was doomed, explaining, “It was part of the five-year plans, approved by the council of ministers and the Politburo. Nobody on a lower level would dare to say a word contradicting those plans, even if it was the fate of the Aral Sea.”

The reaction to the predictions varied. Some Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be “nature’s error”, and a Soviet engineer said in 1968, “it is obvious to everyone that the evaporation of the Aral Sea is inevitable.”

The drying-out of the Aral was not just bad news for the fishermen of the region: it was a full-blown environmental disaster, as the former lake bottom was heavily polluted:

The receding sea has left huge plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals – the results of weapons testing, industrial projects, and pesticides and fertilizer runoff – which are picked up and carried away by the wind as toxic dust and spread to the surrounding area. The land around the Aral Sea is heavily polluted, and the people living in the area are suffering from a lack of fresh water and health problems, including high rates of certain forms of cancer and lung diseases. Respiratory illnesses, including tuberculosis (most of which is drug resistant) and cancer, digestive disorders, anaemia, and infectious diseases are common ailments in the region. Liver, kidney, and eye problems can also be attributed to the toxic dust storms. Health concerns associated with the region are a cause for an unusually high fatality rate amongst vulnerable parts of the population. The child mortality rate is 75 in every 1,000 newborns and maternity death is 12 in every 1,000 women. Crops in the region are destroyed by salt being deposited onto the land. Vast salt plains exposed by the shrinking Aral have produced dust storms, making regional winters colder and summers hotter.

The Aral Sea fishing industry, which in its heyday had employed some 40,000 and reportedly produced one-sixth of the Soviet Union’s entire fish catch, has been devastated, and former fishing towns along the original shores have become ship graveyards. The town of Moynaq in Uzbekistan had a thriving harbor and fishing industry that employed about 30,000 people; now it lies miles from the shore. Fishing boats lie scattered on the dry land that was once covered by water; many have been there for 20 years.

“Waterfront” of Aralsk, Kazakhstan, formerly on the banks of the Aral Sea. Photo taken Spring 2003 by Staecker. (Via Wikipedia)

So, tragic as all this is, what does it have to do with the clothing industry? The Guardian‘s Tansy Hoskins points out that due to the murky supply chains, it’s almost impossible to find out where the cotton used by many international clothing firms actually originates, and the Uzbek cotton fields are worked by forced labour:

The harvest of Uzbek cotton is taking place right now — it started on the 5 September and is expected to last until the end of October. The harvest itself is also a horror story, on top of the environmental devastation, this is cotton picked using forced labour. Every year hundreds of thousands of people are systematically sent to work in the fields by the government.

Under pressure from campaigners, in 2012, Uzbek authorities banned the use of child labour in the cotton harvest, but it is a ban that is routinely flouted. In 2013 there were 11 deaths during the harvest (pdf), including a six year old child, Amirbek Rakhmatov, who accompanied his mother to the fields and suffocated after falling asleep on a cotton truck.

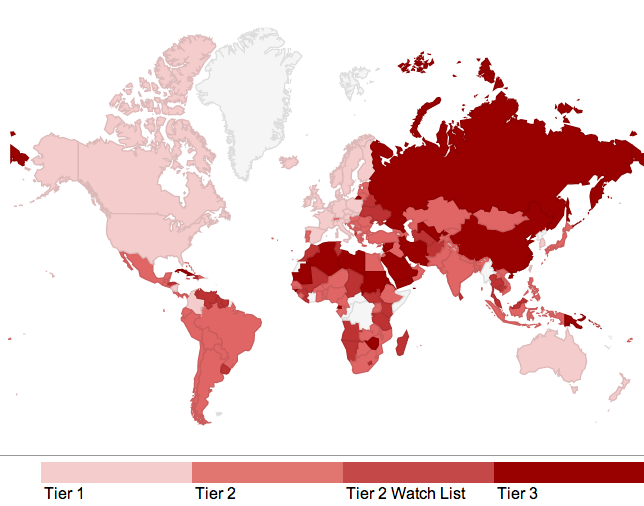

Campaigners have also managed to get 153 fashion brands to sign a pledge to never knowingly use Uzbek cotton. Anti-Slavery International have worked on this fashion campaign but acknowledge that despite successes there is still a long way to go.

“Not knowingly using Uzbek cotton and actually ensuring that you don’t use Uzbek cotton are two completely different things,” explains Jakub Sobik, press officer at Anti-Slavery International.

One major problem that Sobik points out is that much of the Uzbek cotton crop now ends up in Bangladesh and China — key suppliers for European brands. “Whilst it is very hard to trace the cotton back to where it comes from because the supply chain is so subcontracted and deregulated, brands have a responsibility to ensure that slave picked cotton is not polluting their own supply chain.”