This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is an American railway that definitely deserved to call itself “great”, James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railway. Hill was noteworthy as the only “Robber Baron” of that era who was scrupulous in avoiding government entanglements (including grants, loans, subsidies, and other forms of money-with-political-strings-attached), building his entire railway system using private funds and rational profit-oriented economic decision-making (the other transcontinental lines often over-built to claim higher subsidies or added money-losing branch lines to please powerful politicians). The result was that when economic hard times hit the railway business, his was the only transcontinental that never needed to declare bankruptcy.

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is an American railway that definitely deserved to call itself “great”, James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railway. Hill was noteworthy as the only “Robber Baron” of that era who was scrupulous in avoiding government entanglements (including grants, loans, subsidies, and other forms of money-with-political-strings-attached), building his entire railway system using private funds and rational profit-oriented economic decision-making (the other transcontinental lines often over-built to claim higher subsidies or added money-losing branch lines to please powerful politicians). The result was that when economic hard times hit the railway business, his was the only transcontinental that never needed to declare bankruptcy.

In an earlier post, Dane Stuhlsatz summarized the GN’s engineering:

Hill’s line […] was methodically surveyed and built, on the shortest routes possible, with the least gradient possible, and using the best steel and other materials on the market at the time. Rather than political largess, Hill made his decisions based on profit and loss. But, for all the efficiency that Hill built into his line — he was able to transport across the country faster, cheaper, and with less maintenance costs than could the UP and CP — arguably the most important aspect for the viability of his business was the freedom to conduct business untethered by the strings that accompanied government subsidies.

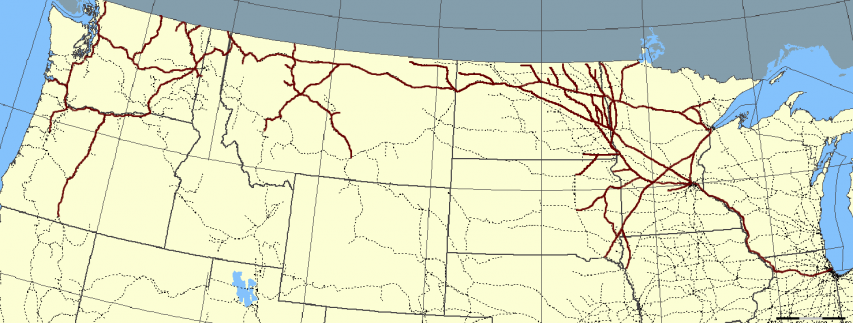

Route map of the Great Northern Railway, circa 1920. Red lines are Great Northern trackage; dotted lines are other railroads.

Map by Elkman via Wikimedia Commons.

George Drury outlines the origins of the railway:

In 1857, the Minnesota & Pacific Railroad was chartered to build a line from Stillwater, Minnesota, on the St. Croix River, through St. Paul and St. Cloud to St. Vincent, in the northwest corner of the state. The company defaulted after completing a roadbed between St. Paul and St. Cloud, Minnesota, and its charter was taken over by the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad, which ran its first train between St. Paul and St. Anthony (now Minneapolis) in 1862.

For financial reasons the railroads were reorganized as the First Division of the St. Paul & Pacific. Both StP&P companies were soon in receivership, and Northern Pacific, with which the StP&P was allied, went bankrupt in the Panic of 1873.

In 1878 James J. Hill and an associate, George Stephen, acquired the two St. Paul & Pacific companies and reorganized them as the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway (“the Manitoba”). By 1885 the company had 1,470 miles of railroad and extended west to Devils Lake, North Dakota. In 1886 Hill organized the Montana Central Railway to build from Great Falls, Montana, through Helena to Butte, and in 1888 the line was opened, creating in conjunction with the StPM&M a railroad from St. Paul to Butte.

In 1881 Hill took over the 1856 charter of the Minneapolis & St. Cloud Railroad. He first used its franchises to build the Eastern Railway of Minnesota from Hinckley, Minnesota, to Superior, Wisconsin, and Duluth. Its charter was liberal enough that he chose it as the vehicle for his line to the Pacific. He renamed the road the Great Northern Railway; it then leased the Manitoba and assumed its operation.

[…]

Even before completion of the route from St. Paul, the Great Northern opened a line along the shore of Puget Sound between Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1891. In the years that followed, Hill pushed a number of lines north across the international boundary into the mining area of southern British Columbia in a running battle with Canadian Pacific. In 1912 GN traded its line along the Fraser River east of Vancouver to Canadian Northern for trackage rights into Winnipeg.

Great Northern gradually withdrew from British Columbia after Hill’s death. In 1909 the Manitoba Great Northern Railway purchased most of the property of the Midland Railway of Manitoba (lines from the U.S. border to Portage la Prairie and to Morden), leaving the Midland, which was jointly controlled by GN and NP, with terminal properties in Winnipeg. The Manitoba Great Northern disposed of its rail lines in 1927. They were later abandoned.

Postcard photo of the Great Northern Railway’s “Empire Builder” streamliner between Everett and Seattle, Washington, circa 1963.

Great Northern Railway postcard via Wikimedia Commons.

The Great Northern and Northern Pacific lines agreed to a merger in 1901 (both lines were controlled by Hill) but the plan was vetoed by the Interstate Commerce Commission. A second attempt in the 1920s after Hill’s death was again turned down by the regulator unless the combined company divested ownership of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy which was both railways’ connection from Minneapolis to Chicago. It was only on the final attempt in 1970 that the deal gained the government’s grudging approval and the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and CB&Q merged to form the Burlington Northern.