What comes next, of course, is that Pyrrhus seemingly fails to capitalize on his victory – but I think in reality the opportunity to capitalize in the way that most folks imagine wasn’t really there.

On Pyrrhus’ side, his army had been bloodied, but was mostly intact and was almost immediately bolstered by the arrival of his Italian allies, including the Lucanians and Samnites, along with the Tarantines. On the Roman side, Laevinius’ army was battered, but still extant; he fell back to Roman-controlled Campania, eventually taking up a position at Capua, the chief city of that region. Pyrrhus then marched north, entering Campania, bypassing the Roman force at Capua (which had been reinforced with two legions pulled from Etruria) and entering Latium, apparently getting within about 60 kilometers (c. 37 miles) of Rome (Plut. Pyrrh. 17.5). And here the question students as is why not take Rome?

And there is an easy answer: because he couldn’t.

The first thing to remember here is the natural of the human-created terrain Pyrrhus has to operate in: functionally all of the cities of any significant size in third-century Italy were likely to be fortified and their populations – thanks to Rome’s recruitment system – experienced and armed. Consequently, if the locals didn’t voluntarily switch sides, Pyrrhus would have been forced to take their settlements either by siege or storm. Pyrrhus might well have hoped that the Campanians would go over to him, but here the problem is the human geography of Italy: his army is full of Samnites, whose emnity with the Campanians is what started the Samnite wars. This is a feature of Rome’s alliance system noted by M.P. Fronda in Between Rome and Carthage (2010): because Rome extended its alliance system by intervening in local rivalries, both sets of new “allies” had long-standing grudges against the other, which makes it hard to dismantle Rome’s alliance network, since any allies you peel away will push others closer to Rome.

In the case of Campania, Capua might have felt strong enough to try their luck without Rome, but that’s why Laevinius was sitting on it with a large army. But the other Campanian cities (of which there were about a dozen) might well fear exposure to Samnite raiding without Rome’s protection. Meanwhile, the Latins – the people of Latium, the region immediately to Rome’s south (technically Rome is in Latium, on its edge) – seem to have been pretty profoundly uninterested in siding against Rome either at this juncture or later when Hannibal tries to dismantle Rome’s alliance system.

So after Heraclea, Pyrrhus has fairly limited options: he can start the slow process of reducing the cities of Campania one by one to open the logistics necessary to permit him to operate long-term in Latium or he can conduct a lightning raid through Roman territory to try to maximize the psychological effect of his victory and perhaps get a favorable peace. He opts for the second choice and when the Romans opt not to take the deal – though they do consider it – he has to pull back to southern Italy (where he focuses on consolidating control, pushing out the last few Roman positions there).

Why not attack Rome directly? Well, Rome itself was fortified, of course. Moreover, the Romans had raised a fresh levy of troops for its defense (Plut. Pyrrh. 18.1), while dispatching Tiberius Corucanius with his army to reinforce Laevinius in Capua. So as Pyrrhus enters Latium, he has a well-defended fortified city in front of him and a Roman army of, conservatively, 30,000 men (Corucanius’ 20,000 men, plus whatever was left of Laevinius’ army) behind him. I don’t usually quote movie tactics, but Ridley Scott’s Saladin has the right wisdom for this problem: “One cannot maintain a siege with the enemy behind“. Had Pyrrhus stopped to besiege Rome, his supply situation would have quickly become hopeless as the Roman army behind him could have easily prevented him from foraging to feed his army during the long process setting up for an assault on the city, which might then simply fail, since the city was well-fortified and defended.

If Plutarch (Pyrrh. 18.4-5) is correct about the terms Pyrrhus offered – an alliance with Rome, a recognition of their hegemony over Italy outside of his new clients in southern Italy (who would of course, fall under Pyrrhus’ control now) – Pyrrhus may have hoped at this juncture to consolidate southern Italy and turn back towards the East or perhaps head on to Sicily. But the Romans refused the deal and so Pyrrhus seems to have set above clearing out the last Roman strongholds (Venusia and Luceria) in Apulia to consolidate his hold. The Romans responded in the following year by sending a new army, under the command of Publius Sulpicius Saverrio and Publius Decius Mus to challenge him and they met at Asculum, in northern Apulia.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIIb: Pyrrhus”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-08.

October 28, 2025

QotD: Pyrrhus after his bloody defeat of the Romans at Heraclea

July 11, 2025

QotD: Pyrrhus arrives in Magna Graecia to support the Tarantines

The Roman response to Pyrrhus’ initial arrival was hardly panic. Military operations in Etruria for 280, under the consul Tiberius Corucanius, continued for the year, while the other consul, Publius Valerius Laevinius, went south to fight Pyrrhus and shore up Rome’s position in Southern Italy. We don’t have clear numbers for the size of the armies at Heraclea – Plutarch stresses that they were big (Plut. Pyrrh. 16.3) – but I think it is fair to suppose that Lavinius probably has a regular consular army with two legions and attached socii, roughly 20,000 men. It has sometimes been supposed this might have been a double-strength army (so 40,000 men) on the basis of some of our sources (including Plutarch) suggesting somewhat nebulously that it was of great size.

There are a few reasons I think this is unlikely. First, sources enlarging armies to fit the narrative magnitude of battles is a very common thing. But more to the point, Pyrrhus has crossed to Italy with 28,500 men total and – as Plutarch notes – hasn’t had a chance to link any of his allies up to his army. That may mean he hasn’t even reabsorbed his scouting force of 3,000 and he may well have also had to drop troops off to hold settlements, secure supplies and so on. Pyrrhus’ initial reluctance to engage (reported by Plutarch) is inconsistent with him wildly outnumbering the Romans, but his decision to wait for reinforcements within reach of the Romans is also inconsistent with the Romans wildly outnumbering him. So a battle in which Pyrrhus has perhaps 20-25,000 men and the Romans a standard two-legion, two-alae army of 20,000 give or take, seems the most plausible.1

The two forces met along the River Siris at Heraclea on the coastal edge of Lucania, Laevinius having pushed deep into southern Italy to engage Pyrrhus. As usual for these battles, we have descriptions or partial descriptions from a host of sources (in this case, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Zonaras, Florus) which don’t always agree, leaving the modern historian in a bit of a pickle. Generally, we assume that a lot of the later Roman narratives of a famous defeat are likely to have been tailored to try and minimize the embarrassment, either by implying the battle was closer than it was or that Pyrrhus was a very impressive foe (or both) or other “face-saving” inventions. Worse yet, all of our sources are writing at substantial chronological distance, the Romans not really having started to record their own history until decades later (though there would have been Greek sources for later historians to work with). Generally, Patrick Kent tends to conclude that – somewhat unusually – Plutarch’s moralizing focus renders him more reliable here: Plutarch feels no need to cover for embarrassing Roman defeats or to embellish battle narratives (which he’d rather keep short, generally) because his focus is on the character of Pyrrhus. Broadly speaking, I think that’s right and so I too am going to generally prefer Plutarch’s narratives here.

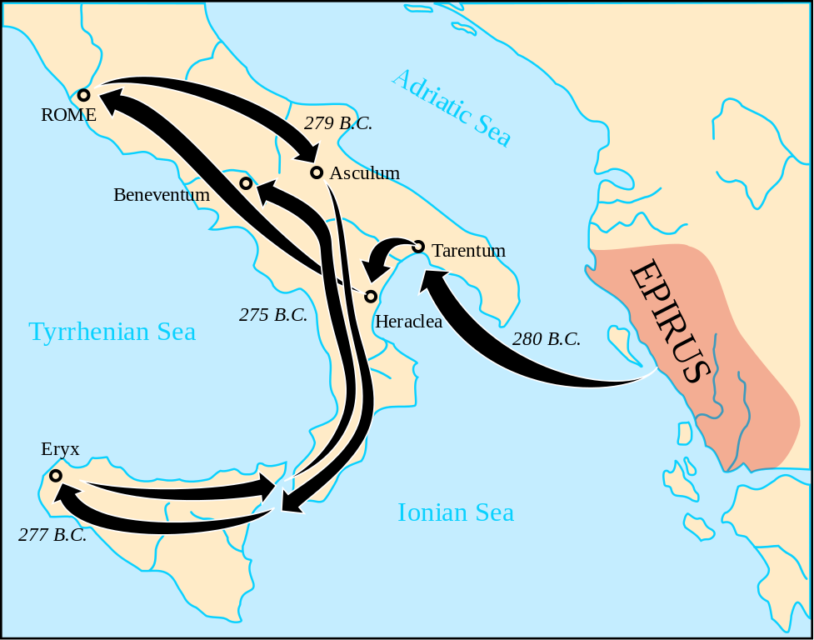

A fairly handy map of Pyrrhus’ campaigns (though some of the detail is lost in the big sweeping arrows). What is notable is, apart from Pyrrhus’ lightning raid into Latium in 280, he is almost invariably fighting in “friendly” territory, either in Lucania (Heraclea), Apulia (Asculum) or Samnium (Beneventum), the lands of his allies. Pyrrhus never fights an actual pitched battle on Roman-controlled territory, which I think speaks to his strategic intent: to carve out a kingdom in Greater Greece, not to conquer the whole of Italy.

Wikimedia Commons.The battle was defined by Pyrrhus’ use of terrain – Pyrrhus thought delay might be wiser (to link up with his allies) but left a blocking force on the river (the Romans being on the other side). The Romans responded by forcing the river – typical Roman aggression – but Plutarch at least thinks it caught Pyrrhus by surprise (he hadn’t fought Romans before) and so it leaves him in a scramble. He charges his cavalry (Plut. Pyrrh. 16.5) to give his main phalanx time to form up for battle resulting in what seems like a cavalry engagement near the river. Pyrrhus nearly gets himself killed in the fighting, but survives and falls back to his main infantry force, which then met the Romans in an infantry clash. The infantry fighting was fierce according to Plutarch and Pyrrhus, still shaken from being almost killed, had to come out and rally his troops. In the end, the Romans are described as hemmed in by Pyrrhus’ infantry and elephants before some of his Greek cavalry – from Thessaly, the best horse-country in Greece – delivers the decisive blow, routing the Roman force.

It is, on the one hand, a good example of the Hellenistic army “kit” using almost all of its tactical elements: an initial – presumably light infantry – screen holding the river, followed by a cavalry screen to enable the phalanx to deploy, then a fierce and even infantry fight, finally decided by what seems to be flanking actions by cavalry and elephants. Plutarch (Pyrrh. 17.4) gives two sets of casualty figures, one from Dionysius and another from Hieronymus; the former says that the Romans lost 15,000 to Pyrrhus’ 13,000 killed, the latter that the Romans lost 7,000 to Pyrrhus’ just a bit less than 4,000 killed. The latter seems almost certainly more accurate. In either case, the Roman losses were heavier, but Pyrrhus’ losses were significant and as Plutarch notes, his losses were among his best troops.

Even in the best case, in victory, Pyrrhus had lost around 15% of his force (~4,000 out of 28,000), a heavy set of losses. Indeed, normally if an army loses 15% of its total number in a battle, we might well assume they lost. Roman losses, as noted, were heavier still, but as we’ve discussed, the Romans have strategic depth (in both geography, political will and military reserves) – Pyrrhus does not. By contrast, Alexander III reportedly wins at Issus (333) with just 150 dead (and another 4,802 wounded or missing; out of c. 37,000) and at Gaugamela (331) with roughly 1,500 losses (out of c. 47,000). The Romans will win at Cynoscephelae (197) with just 700 killed.

This isn’t, I think, a product of Pyrrhus failing at all, but rather a product of the attritional nature of Roman armies: even in defeat they draw blood. Even Hannibal’s great victory at Cannae (216) costs him 5,700 men, according to Polybius (more, according to Livy). But the problem for Pyrrhus is that his relatively fragile Hellenistic army isn’t built to repeatedly take those kinds of hits: Pyrrhus instead really needs big blow-out victories where he takes few losses and destroys or demoralizes his enemy. And the Roman military system does not offer such one-sided battles often.

Nevertheless, Pyrrhus shows that a Hellenistic army, capable handled, could beat a third-century Roman army, albeit not cleanly, and that is well worth noting.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIIb: Pyrrhus”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-08.

1. I should note, this is Kent’s assessment as well.

February 10, 2025

QotD: The Roman Republic versus the heirs of Alexander the Great

Last time, we finished our look at the third-century successes of the phalanx with the career of Pyrrhus of Epirus, concluding that even when handled very well with a very capable body of troops, Hellenistic armies struggled to achieve the kind of decisive victories they needed against the Romans to achieve strategic objectives. Instead, Pyrrhus was able to achieve a set of indecisive victories (and a draw), which was simply not anywhere close to enough in view of the tremendous strategic depth of Rome.

Well, I hope you got your fill of Hellenistic armies winning battles because it is all downhill from here (even when we’re fighting uphill). For the first half of the second century, from 200 to 168, the Romans achieve an astounding series of lopsided victories against both (Antigonid) Macedonian and Seleucid Hellenistic armies, while simultaneously reducing several other major players (Pergamon, Egypt) to client states. And unlike Pyrrhus, the Romans are in a position to “convert” on each victory, successfully achieving their strategic objectives. It was this string of victories, so shocking in the Greek world, that prompted Polybius to write his own history, covering the period from 264 to 146 to try to explain what the heck happened (much of that history is lost, but Polybius opens by suggesting that anyone paying attention to the First Punic War (264-241) ought to have seen this coming).

That said, this series of victories is complex. Of the five major engagements (The River Aous, Cynoscephalae, Thermopylae, Magnesia, and Pydna) Rome commandingly wins all of them, but each battle is strange in its own way. So we’re going to look at each battle and also take a chance to lay out a bit of the broader campaigns, asking at each stage why does Rome win here? Both in the tactical sense (why do they win the battle) and also in the strategic sense (why do they win the war).

We’re going to start with the war that brought Rome truly into the political battle royale of the Eastern Mediterranean, the Second Macedonian War (200-196). Rome was acting, in essence, as an interloper in long-running conflicts between the various successor dynasties of Alexander the Great as well as smaller Greek states caught in the middle of these larger brawling empires. Briefly, the major players are the Ptolemaic Dynasty, in Egypt (the richest state), the Seleucid Dynasty out of Syria and Mesopotamia (the largest state) and the Antigonid Kingdom in Macedonia (the smallest and weakest state, but punching above its weight with the best man-for-man army). The minor but significant players are the Attalid dynasty in Pergamon, a mid-sized Hellenistic power trapped between the ambitions of the big players, two broad alliances of Greek poleis in the Greek mainland the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues, and finally a few freewheeling poleis, notably Athens and Rhodes. The large states are trying to dominate the system, the small states trying to retain their independence and everyone is about to get rolled by the Romans.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVa: Philip V”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-15.

September 29, 2024

QotD: Pyrrhus, King of Epirus

Last time, we sought to assess some of the assumed weaknesses of the Hellenistic phalanx in facing rough terrain and horse archer-centered armies and concluded, fundamentally, that the Hellenistic military system was one that fundamentally worked in a wide variety of environments and against a wide range of opponents.

This week, we’re going to look at Rome’s first experience of that military system, delivered at the hands of Pyrrhus, King of Epirus (r. 297-272). The Pyrrhic Wars (280-275) are always a sticking point in these discussions, because they fit so incongruously with the rest. From 214 to 148, Rome will fight four “Macedonian Wars” and one “Syrian War” and utterly demolish every major Hellenistic army it encounters, winning every single major pitched battle and most of them profoundly lopsidedly. Yet Pyrrhus, fighting the Romans some 65 years earlier manages to defeat Roman armies twice and fight a third to a messy draw, a remarkably better battle record than any other Hellenistic monarch will come anywhere close to achieving. At the same time, Pyrrhus, quite famously, fails to get anywhere with his victories, taking losses he can ill-afford each time (thus the notion of a “Pyrrhic victory”), while the Roman armies he fights are never entirely destroyed either.

So we’re going to take a more in-depth look at the Pyrrhic Wars, going year-by-year through the campaigns and the three major battles at Heraclea (280), Ausculum (279) and Beneventum (275) and try to see both how Pyrrhus gets a much better result than effectively everyone else with a Hellenistic army and also why it isn’t enough to actually defeat the Romans (or the Carthaginians, who he also fights). As I noted last time, I am going to lean a bit in this reconstruction on P.A. Kent, A History of the Pyrrhic War (2020), which does an admirable job of untangling our deeply tangled and honestly quite rubbish sources for this important conflict.

Believe it or not, we are actually going to believe Plutarch in a fair bit of this. So, you know, brace yourself for that.

Now, Pyrrhus’ campaigns wouldn’t have been possible, as we’ll note, without financial support from Ptolemy II Philadelphus, Antigonus II Gonatus and Ptolemy Keraunos. So, as always, if you want to help me raise an Epirote army to invade Italy (NATO really complicates this plan, as compared to the third century, I’ll admit), you can support this project on Patreon.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIIb: Pyrrhus”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-08.

May 9, 2024

QotD: Rome’s socii system

The earliest indicator we have of what is going to be Rome’s socii-system is the Foedus Cassianum (“Cassius’ Treaty”) concluded with the communities of Latium – the Latins – in 493. That is, of course, quite an early date and while we have narratives of these events from both Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, we have to be quite cautious as they are operating at great chronological remove (both writing in the first century B.C.) and with limited sources (something both actually more or less admit). According to Livy (2.18) the issue had begun with thirty Latin towns conspiring in a league against Rome (which does not yet have any imperial holdings), to which Rome responded by going to war. The timing, just a few years after the expulsion of Rome’s kings and the formation of the res publica may be suggestive that the Latins had formed this league to take advantage of the political crisis in Rome, which was the largest town in Latium, in order to throw off whatever Roman influence they may have been under during the period of the kings.

In any case, the Romans win the war and impose a peace treaty the terms of which, according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus went thusly:1

Let there be peace between the Romans and all the Latin cities as long as the heavens and the earth shall remain where they are. Let them neither make war upon another themselves nor bring in foreign enemies nor grant a safe passage to those who shall make war upon either. Let them assist one another, when warred upon, with all their forces, and let each have an equal share of the spoils and booty taken in their common wars. Let suits relating to private contracts be determined within ten days, and in the nation where the contract was made. And let it not be permitted to add anything to, or take anything away from these treaties except by the consent both of the Romans and of all the Latins.

This is the origin point for Rome’s use of what I’ve termed the “Goku Model of Imperialism” – “I beat you, therefore we are friends”. Having soundly defeated – at least according to our sources – the Latins, Rome doesn’t annex or destroy them, nor does it impose tribute, but rather imposes a treaty of alliance on them (in practice I suspect we might want to understand that Rome’s position was not so dominant as our sources suggest, thus the relatively good terms the Latins get). The treaty sounds like an equal relationship, until one remembers that it is the entire Latin league – thirty or more communities – as one party and then just Rome as the other party.

Rome proceeds, in the century or so that follows, to use this alliance to defeat their other neighbors, both the nearest major Etruscan centers as well as the Aequi and Sabines who lived in the hills to the north-east of Rome and the Volsci who lived to the south of Latium. Roman relations with the Latins seem to fray in the early 300s, presumably because the greatest threat to their communities was increasingly not the Volsci, but Rome’s emerging regional power. That leads to a collapse of the Foedus Cassianum in 341 and another war between Rome and the Latin League. Once again our sources are much later, so we might be somewhat skeptical of the details they provide, but the upshot is that at the end the Romans won by 338.

Rome’s expansion into most areas follows a familiar pattern: Rome enters a region by concluding an alliance with some weaker power in a region and then rushing to the aid of that weaker power; in some cases this was a long-term relationship that had been around for some time (like the long Roman friendship with Etruscan Caere) and in some cases it was a very new and opportunistic friendship (as with Capua’s appeal to the Romans for aid in 343). In either case, Rome formed a treaty with the community it was “protecting” and then moved against its local enemies. Once defeated, it imposed treaties on them, too. Rome might also seize land in these wars from the defeated party (before it imposed that treaty); if these were far away, Rome might settle a colony on that land rather than annexing it into Rome’s core territory (the ager Romanus). These new communities – the Latin colonies – were created with treaty obligations towards Rome.

Note the change: what was initially an alliance between one party (Rome) and another party (the Latin League) has instead become an alliance system, a series of bilateral treaties between Rome and a slew of smaller communities. And they were smaller, because Rome often took land in these wars, so that by the third century, the Roman citizen body represented roughly 40% of the total, making Rome much bigger than any other allied community. This shift was probably gradual, rather than there being some dramatic policy change at any point. Rome accrued its Italian empire the same way it would accrue its Mediterranean one: as a result of a series of localized, ad hoc decisions which collectively added up to the result without ever being intended to constitute a single, unified policy.

The Romans called all of these allied communities and their people socii, “allies” – a bit of a euphemism, because these were no longer equal alliances. We’ll get into the terms in a moment, but it seems clear that by 338 that these “allies” are promising to have no foreign policy save for their alliance with Rome and to contribute soldiers to Roman armies. So Rome is in the driver’s seat determining where the alliance will go; Rome does not have to consult the allies when it goes to war and indeed does not do so. The socii cannot take Rome to war (but Rome will go to war immediately if a community of socii is attacked). This is no longer an equal arrangement, but it is useful for the Romans to pretend it is.

The next major series of Roman conflicts are with the Samnites. Rome is, according to Livy, at least, drawn into fighting the Samnites because of its suddenly concluded alliance with Capua and the Campanians (though Rome had been more loosely allied to the Samnites shortly before). In practice, the first two Samnite Wars (343-341, 326-304) were fought to determine control over Campania and the Bay of Naples, with Rome fighting to expand its influence there (by making those communities allies or protecting those who were) while the Samnites pushed back.

The Third Samnite War (298-290) becomes something rather different: a containment war. Rome’s growing power – through its “alliance” system – was clearly on a course to dominate the peninsula, so a large coalition of opponents, essentially every meaningful Italian power not already in Rome’s alliance system, banded together in a coalition to try to stop it (except for the Greeks). What started as another war between Rome and the Samnites soon pulled in the remaining independent Etruscan powers and then even a Gallic tribe (the Senones) in an effort to contain Rome. The Romans manage to pull out a victory (though it was a close run thing) and in the process managed to pull yet more communities into the growing alliance system. It seems – the sources here are confused – that the decade that followed, the Romans lock down much of Etruria as well.

The Greek cities in southern Italy now at last recognize their peril and call in Pyrrhus of Epirus to try to beat back Rome, leading to the Pyrrhic War (280-275). Pyrrhus wins some initial battles but – famously – at such cost that he is unable to win the war. Pyrrhus withdraws in 275 and Rome is then able over the next few years to mop up the Greek cities in Southern Italy, with the ringleader, Tarentum, falling to Rome in 272. Rome imposed treaties on them, too, pulling them into the alliance system. Thus, by 264 Rome’s alliance system covered essentially the whole of Italy South of the Po River. It had emerged as an ad hoc system and admittedly our sources don’t give us a good sense of how and when the terms of the alliance change; in many cases it seems our sources, writing much later, may not know. They have the foedus Cassianum, with its rather more equal terms, and knowledge of the system as it seems to have existed in the late third century and the dates and wars by which this or that community was voluntarily or forcibly integrated, but not the details of by what terms and so on.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Addenda: The Socii“, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-10-20.

1. trans. Earnest Clay (1940).

May 27, 2023

QotD: The war elephant’s primary weapon was psychological, not physical

The Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC), which I’ve discussed here is instructive. Porus’ army deployed elephants against Alexander’s infantry – what is useful to note here is that Alexander’s high quality infantry has minimal experience fighting elephants and no special tactics for them. Alexander’s troops remained in close formation (in the Macedonian sarissa phalanx, with supporting light troops) and advanced into the elephant charge (Arr. Anab. 5.17.3) – this is, as we’ll see next time, hardly the right way to fight elephants. And yet – the Macedonian phalanx holds together and triumphs, eventually driving the elephants back into Porus’ infantry (Arr. Anab. 5.17.6-7).

So it is possible – even without special anti-elephant weapons or tactics – for very high quality infantry (and we should be clear about this: Alexander’s phalanx was as battle hardened as troops come) to resist the charge of elephants. Nevertheless, the terror element of the onrush of elephants must be stressed: if being charged by a horse is scary, being charged by a 9ft tall, 4-ton war beast must be truly terrifying.

Yet – in the Mediterranean at least – stories of elephants smashing infantry lines through the pure terror of their onset are actually rare. This point is often obscured by modern treatments of some of the key Romans vs. Elephants battles (Heraclea, Bagradas, etc), which often describe elephants crashing through Roman lines when, in fact, the ancient sources offer a somewhat more careful picture. It also tends to get lost on video-games where the key use of elephants is to rout enemy units through some “terror” ability (as in Rome II: Total War) or to actually massacre the entire force (as in Age of Empires).

At Bagradas (255 B.C. – a rare Carthaginian victory on land in the First Punic War), for instance, Polybius (Plb. 1.34) is clear that the onset of the elephants does not break the Roman lines – if for no other reason than the Romans were ordered quite deep (read: the usual triple Roman infantry line). Instead, the elephants disorder the Roman line. In the spaces between the elephants, the Romans slipped through, but encountered a Carthaginian phalanx still in good order advancing a safe distance behind the elephants and were cut down by the infantry, while those caught in front of the elephants were encircled and routed by the Carthaginian cavalry. What the elephants accomplished was throwing out the Roman fighting formation, leaving the Roman infantry confused and vulnerable to the other arms of the Carthaginian army.

So the value of elephants is less in the shock of their charge as in the disorder that they promote among infantry. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, heavy infantry rely on dense formations to be effective. Elephants, as a weapon-system, break up that formation, forcing infantry to scatter out of the way or separating supporting units, thus rendering the infantry vulnerable. The charge of elephants doesn’t wipe out the infantry, but it renders them vulnerable to other forces – supporting infantry, cavalry – which do.

Elephants could also be used as area denial weapons. One reading of the (admittedly somewhat poor) evidence suggests that this is how Pyrrhus of Epirus used his elephants – to great effect – against the Romans. It is sometimes argued that Pyrrhus essentially created an “articulated phalanx” using lighter infantry and elephants to cover gaps – effectively joints – in his main heavy pike phalanx line. This allowed his phalanx – normally a relatively inflexible formation – to pivot.

This area denial effect was far stronger with cavalry because of how elephants interact with horses. Horses in general – especially horses unfamiliar with elephants – are terrified of the creatures and will generally refuse to go near them. Thus at Ipsus (301 B.C.; Plut. Demetrius 29.3), Demetrius’ Macedonian cavalry is cut off from the battle by Seleucus’ elephants, essentially walled off by the refusal of the horses to advance. This effect can resolved for horses familiarized with elephants prior to battle (something Caesar did prior to the Battle of Thapsus, 46 B.C.), but the concern seems never to totally go away. I don’t think I fully endorse Peter Connolly’s judgment in Greece and Rome At War (1981) that Hellenistic armies (read: post-Alexander armies) used elephants “almost exclusively” for this purpose (elephants often seem positioned against infantry in Hellenistic battle orders), but spoiling enemy cavalry attacks this way was a core use of elephants, if not the primary one.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.

November 24, 2022

QotD: Roman legionary fortified camps

The degree to which we should understand the Roman habit of constructing fortified marching camps every night as exceptional is actually itself an interesting question. Our sources disagree on the origins of the Roman fortified camp; Frontinus (Front. Strat 4.1.15) says that the Romans learned it from the Macedonians by way of Pyrrhus of Epirus but Plutarch (Plut. Pyrrhus 16.4) represents it the other way around; Livy, more reliable than either agrees with Frontinus that Pyrrhus is the origin point (Liv. 35.14.8) but also has Philip V, a capable Macedonian commander, stand in awe of Roman camps (Liv. 31.34.8). It’s clear there was something exceptional about the Roman camps because so many of our sources treat it as such (Liv. 31.34.8; Plb. 18.24; Josephus BJ 3.70-98). Certainly the Macedonians regularly fortified their camps (e.g. Plb. 18.24; Liv 32.5.11-13; Arr. Alex. 3.9.1, 4.29.1-3; Curtius 4.12.2-24, 5.5.1) though Carthaginian armies seem to have done this less often (e.g. Plb. 6.42.1-2 encamping on open ground is treated as a bold new strategy).

It is probably not the camps themselves, but their structure which was exceptional. Polybius claims Greeks “shirk the labor of entrenching” (Plb. 6.42.1-2) and notes that the stakes the Romans used to construct the wooden palisade wall of the camp are more densely placed and harder to remove (Plb. 18.18.5-18). The other clear difference Polybius notes is the order of Roman camps, that the Romans lay out their camp the same way wherever it is, whereas Greek and Macedonian practice was to conform the camp to the terrain (Plb. 6.42); the archaeology of Roman camps bears out the former whereas analysis of likely battlefield sites (like the Battle of the Aous) seem to bear out the latter.

In any case, the mostly standard layout of Roman marching camps (which in the event the Romans lay siege, become siege camps) enables us to talk about the Roman marching camp because as far as we can tell they were all quite similar (not merely because Polybius says this, but because the basic features of these camps really do seem to stay more or less constant.

The basic outline of the camp is a large rectangle with the corners rounded off, which has given the camps (and later forts derived from them) their nickname: “playing card” forts. The size and proportions of a fortified camp would depend on the number of legions, allies and auxiliaries present, from nearly square to having one side substantially longer than the other. This isn’t the place to get into the internal configuration of the camp, except to note that these camps seemed to have been standardized so that the layout was familiar to any soldier wherever they went, which must have aided in both building the camp (since issues of layout would become habit quickly) and packing it up again.

Now a fortified camp does not have the same defensive purpose as a walled city: the latter is intended to resist a siege, while a fortified camp is mostly intended to prevent an army from being surprised and to allow it the opportunity to either form for battle or safely refuse battle. That means the defenses are mostly about preventing stealthy approach, slowing down attackers and providing a modest advantage to defenders with a relative economy of cost and effort.

In the Roman case, for a completed defense, the outermost defense was the fossa or ditch; sources differ on the normal width and depth of the ditch (it must have differed based on local security conditions) but as a rule they were at least 3′ and 5′ wide and often significantly more than this (actual measured Roman defensive fossae are generally rather wider, typically with a 2:1 ratio of width to depth, as noted by Kate Gilliver. The earth excavated to make the fossa was then piled inside of it to make a raised earthwork rampart the Romans called the agger. Finally, on top of the agger, the Romans would place the valli (“stakes”) they carried to make the vallum. Vallum gives us our English word “wall” but more nearly means “palisade” or “rampart” (the Latin word for a stone wall is more often murus).

Polybius (18.18) notes that Greek camps often used stakes that hadn’t had the side branches removed and spaced them out a bit (perhaps a foot or so; too closely set for anyone to slip through); this sort of spaced out palisade is a common sort of anti-ambush defense and we know of similar village fortifications in pre- and early post-contact North America on the East coast, used to discourage raids. Obviously the downside is that when such stakes are spaced out, it only takes the removal of a few to generate a breach. The Roman vallum, by contrast, set the valli fixed close together with the branches interlaced and with the tips sharpened, making them difficult to climb or remove quickly.

The gateway obviously could not have the ditch cut across the entryway, so instead a second ditch, the titulum, was dug 60ft or so in front of the gate to prevent direct approach; the gate might also be reinforced with a secondary arc of earthworks, either internally or externally, called the clavicula; the goal of all of this extra protection was again not to prevent a determined attacker from reaching the gates, but rather to slow a surprise attack down to give the defender time to form up and respond.

And that’s what I want to highlight about the nature of the fortified Roman camp: this isn’t a defense meant to outlast a siege, but – as I hinted at last time – a defense meant to withstand a raid. At most a camp might need to withstand the enemy for a day or two, providing the army inside the opportunity to retreat during the night.

We actually have some evidence of similar sort of stake-wall protections in use on the East Coast of Native North America in the 16th century, which featured a circular stake wall with a “baffle gate” that prevented a direct approach and entrance. The warfare style of the region was heavily focused on raids rather than battles or sieges (though the former did happen) in what is sometimes termed the “cutting off way of war” (on this see W. Lee, “The Military Revolution of Native North America” in Empires and Indigines, ed. W. Lee (2011)). Interestingly, this form of Native American fortification seems to have been substantially disrupted by the arrival of steel axes for presumably exactly the reasons that Polybius discusses when thinking about Greek vs. Roman stake walls: pulling up a well-made (read: Roman) stake wall was quite difficult. However, with steel axes (imported from European traders), Native American raiding forces could quickly cut through a basic palisade. Interestingly, in the period that follows, Lee (op. cit.) notes a drift towards some of the same methods of fortification the Romans used: fortifications begin to square off, often combined a ditch with the palisade and eventually incorporated corner bastions projecting out of the wall (a feature Roman camps do not have, but later Roman forts eventually will, as we’ll see).

Roman field camps could be more elaborate than what I’ve described; camps often featured, for instance, observation towers. These would have been made of wood and seem to have chiefly been elevated posts for lookouts rather than firing positions, given that they sit behind the vallum rather than projecting out of it (meaning that it would be very difficult to shoot any enemy who actually made it to the vallum from the tower).

When a Roman army laid siege to a fortified settlement, the camp formed the “base” from which siege works were constructed (particularly circumvallation – making a wall around the enemy’s city to keep them in – and contravallation – making a wall around your siege position to keep other enemies out. We’ll discuss these terms in more depth a little later). Some of the most elaborate such works we have described are Caesar’s fortifications at the Siege of Alesia (52 BC; Caes. B.G. 7.72). There the Roman line consisted of an initial trench well beyond bow-shot range from his planned works in order to prevent the enemy from disrupting his soldiers with sudden attacks, then an agger and vallum constructed with a parapet to allow firing positions from atop the vallum, with observation towers every 80 feet and two ditches directly in front of the agger, making for three defensive ditches in total (be still Roel Konijnendijk‘s heart! – but seriously, the point he makes on those Insider “Expert Rates” videos about the importance of ditches are, as you can tell already, entirely accurate), which were reinforced with sharpened stakes faced outward. As Caesar expressly notes, these weren’t meant to be prohibitive defenses that would withstand any attack – wooden walls can be chopped or burned, after all – but rather to give him time to respond to any effort by the defenders to break out or by attackers to break in (he also contravallates, reproducing all of these defenses facing outward, as well).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part II: Romans Playing Cards”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-11-12.

January 20, 2020

Pyrrhus of Epirus: Enemy of Rome

History Time

Published 2 Dec 2017A brief look at one of the first and greatest adversaries of the Romans.

Some of the maps used in this and other History Time videos were produced by the incredible Battles of the Ancients. Check out the awesome website below for your ancient history fix.

http://turningpointsoftheancientworld.com/Music:-

Two Steps From Hell – “Hearts of Courage”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eYj8c…

BrunuhVille – “Song of the North” (Alt. Version)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHAFr…

Adrian Von Ziegler – “Moonsong”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifQ3J…If you liked this video and have a spare dollar you can help to support the channel here:-

http://www.patreon.com/historytimeUKAre you a budding artist, illustrator, cartographer, or music producer? Send me a message! No matter how professional you are or even if you’re just starting out, I can always use new music and images in my videos. Get in touch! I’d love to hear from you.

I’ve also compiled a reading list of my favourite history books via the Amazon influencer program. If you do choose to purchase any of these incredible sources of information, many of which form the basis of my videos, then Amazon will send me a tiny fraction of the earnings (as long as you do it through the link) (this means more and better content in the future) I’ll keep adding to and updating the list as time goes on:-

https://www.amazon.com/shop/historytimeI try to use copyright free images at all times. However if I have used any of your artwork or maps then please don’t hesitate to contact me and I’ll be more than happy to give the appropriate credit.

—Join the History Time community on social media:-

Patreon:-

https://www.patreon.com/historytimeUK

Instagram:-

https://www.instagram.com/historytime…

Twitter:-

https://twitter.com/HistoryTimeUK