Published on 26 Feb 2015

To break up the stalemate and get a decisive advantage, France and Great Britain open up yet another theatre of war in the Dardanelles. The plan is to seize the strait and open eventually open up the Bosporus in order to ship supplies to the Eastern and Balkan front. And so begins the naval bombardment of ottoman forts as prelude to a big offensive which will we know to today as Gallipoli.

February 27, 2015

Prelude to Gallipoli – Naval Bombardement of the Dardanelles I THE GREAT WAR Week 31

January 9, 2015

In Dire Straits – Russia on Austro-Hungary’s Doorstep I THE GREAT WAR Week 24

Published on 8 Jan 2015

The Austro-Hungarian army resembles a better militia after six months into the war. After defeats against Serbia and Russia and still under siege in Galicia, the forces are in dire straits. Many casualties, especially among the officers, mean that an effective warfare is impossible. And all this while the Russians are close to entering the Hungarian plains. On another front, the Russians are winning the battle of Sarikamish which ends in a disaster for the Ottoman Empire. On the Western Front, each side still tries to gain a decisive advantage.

January 2, 2015

The Ottoman Disaster – The Battle of Sarikamish I THE GREAT WAR Week 23

Published on 1 Jan 2015

The Champagne offensive is still going on the Western Front without any side gaining a decisive advantage. In the Caucasus, Enver Pasha is showing how far he’s willing to go to achieve his goals. Against his military advisors’ recommendations, he decides to send more and more troops to Sarikamish. Without supplies and with temperatures constantly below -20 degrees, thousands of them freeze to death before even reaching the frontline. When the Russians finally encircle the Ottoman Troops, defeat is inevitable.

December 26, 2014

The First Battle of Champagne – Dying In Caucasus Snow I THE GREAT WAR Week 22

Published on 25 Dec 2014

Right before Christmas the allied powers begin the Champagne offensive, which will last several months. In the snow and the mud, and under horrible living conditions not only the soldiers suffer. The images of a war fought with honour and glory are finally over as even the white flag is used for ambushes. Far away in the mountains of the Caucasian, Russia and the Ottoman Empire are fighting a grim battle, too, in which many soldiers die during interminable marches in the snow wearing summer uniforms.

November 10, 2014

The World at War – The Ottoman Empire Enters The Stage I THE GREAT WAR Week 15

Published on 6 Nov 2014

Three months after the outbreak of the war, another world power enters the conflict: The Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman war minister Enver Pasha, a supporter of a new Turkish self confidence, wants to gain advantages for a future Turkey by declaring war. Meanwhile, another ship of the German East Asian Squadron is surprising the Royal Navy by sinking two of their ships near Coronel, Chile. Regardless, the battles on the Eastern, Western Front and in Serbia are continuing.

August 27, 2014

The Congress System, the Holy Alliance and the re-ordering of Europe in the nineteenth century

In my ongoing origins of World War 1 series, I took a bit of time to discuss the Congress of Vienna and the diplomatic and political system it created for nearly one hundred years of (by European standards) peaceful co-existence. Not that it completely prevented wars (see the rest of the series for a partial accounting of them), but that it provided a framework within which the great powers could attempt to order affairs without needing to go to war quite as often. In the current issue of History Today, Stella Ghervas goes into more detail about the congress itself and the system it gave birth to:

Emperor Napoleon was defeated in May 1814 and Cossacks marched along the Champs-Elysées into Paris. The victorious Great Powers (Russia, Great Britain, Austria and Prussia) invited the other states of Europe to send plenipotentiaries to Vienna for a peace conference. At the end of the summer, emperors, kings, princes, ministers and representatives converged on the Austrian capital, crowding the walled city. The first priority of the Congress of Vienna was to deal with territorial issues: a new configuration of German states, the reorganisation of central Europe, the borders of central Italy and territorial transfers in Scandinavia. Though the allies came close to blows over the partition of Poland, by February 1815 they had averted a new war thanks to a series of adroit compromises. There had been other pressing matters to settle: the rights of German Jews, the abolition of the slave trade and navigation on European rivers, not to mention the restoration of the Bourbon royal family in France, Spain and Naples, the constitution of Switzerland, issues of diplomatic precedence and, last but not least, the foundation of a new German confederation to replace the defunct Holy Roman Empire.

[…]

Surprisingly, the Russian view on peace in Europe proved by far the most elaborate. Three months after the final act of the Congress, Tsar Alexander proposed a treaty to his partners, the Holy Alliance. This short and unusual document, with Christian overtones, was signed in Paris on September 1815 by the monarchs of Austria, Prussia and Russia. There is a polarised interpretation, especially in France, that the ‘Holy Alliance’ (in a broad sense) had only been a regression, both social and political. Castlereagh joked that it was a ‘piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense’, even though he recommended Britain to undersign it. Correctly interpreting this document is key to understanding the European order after 1815.

While there was undoubtedly a mystical air to the zeitgeist, we should not stop at the religious resonances of the treaty of the Holy Alliance, because it also contained some realpolitik. The three signatory monarchs (the tsar of Russia, the emperor of Austria and the king of Prussia) were putting their respective Orthodox, Protestant and Catholic faiths on an equal footing. This was nothing short of a backstage revolution, since they relieved de facto the pope from his political role of arbiter of the Continent, which he had held since the Middle Ages. It is thus ironic that the ‘religious’ treaty of the Holy Alliance liberated European politics from ecclesiastical influence, making it a founding act of the secular era of ‘international relations’.

There was, furthermore, a second twist to the idea of ‘Christian’ Europe. Since the sultan of the Ottoman Empire was a Muslim, the tsar could conveniently have it both ways: either he could consider the sultan as a legitimate monarch and be his friend; or else think of him as a non-Christian and become his enemy. As a matter of course, Russia still had territorial ambitions south, in the direction of Constantinople. In this ambiguity lies the prelude to the Eastern Question, the struggle between the Great Powers over the fate of the Ottoman Empire (the ‘sick man of Europe’), as well as the control of the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Much to his credit, Tsar Alexander did not profit from that ambiguity, but his brother and successor Nicholas soon started a new Russo-Turkish war (1828-29).

August 18, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part eleven of a series)

You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here (now with hopefully helpful descriptions):

- Why it’s so difficult to answer the question “Who is to blame?”

- Looking back to 1814

- Bismarck, his life and works

- France isolated, Britain’s global responsibilities

- Austria, Austria-Hungary, and the Balkan quagmire

- The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- The First Balkan War

- The Second Balkan War

- The Entente Cordiale, Moroccan crises, and the influence of public opinion

We left the Austro-Hungarian Empire in a state of ferment back in part five, having undergone a near-death constitutional stroke in 1867, resulting in a bi-polar domestic and even world outlook to accommodate the newly redefined Dual Monarchy, and dangerously inconsistent treatment of their respective ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities in the Cisleithanic (Austrian) and Transleithanic (Hungarian) “halves” of the empire. This might not have mattered much in the long run if the empire hadn’t been summarily extended in 1908 with the addition of new territory on the southern border of the empire.

Administration turns into annexation

Under the terms of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, Austria-Hungary had been administering the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the provision that they would be returned at some future date when the stability of the occupied territories had been re-established. In 1908, however, something happened which drove the Austro-Hungarians into a panic: the somnolent Ottoman government was faced with a revolutionary movement called the Young Turks.

Since 1878, the Sultan had ruled without a parliament, having suspended the General Assembly and ending the short-lived First Constitutional Era. The Young Turks were an unlikely alliance of Turkish nationalists, reformers, pro-Western modernizers, and certain national minorities including Armenians and Greeks: in short, anyone with a grievance against the Sultan, the administration, or the general state of life in the empire. The Young Turks forced the Sultan to restore the 1876 constitution and recall the general assembly. They also announced plans to call elections throughout the empire, including the Austrian-occupied territories.

Bosnia and Herzegovina had no existing representation of any sort — with the Ottomans or with the Austrians — and it was feared that the Young Turks, having created representation in the two vilayets would then demand their return to Ottoman control. Austria’s foreign minister, Count Alois von Aehrenthal began to make urgent plans to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina. In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark outlines Aehrenthal’s actions:In 1908, having successfully negotiated Russian support for the move, Austria-Hungary swallowed the two provinces and added them to the empire. Then things went horribly, horribly wrong for Aehrenthal and Austria-Hungary. The reaction to annexation was far more angry and widespread than Aehrenthal had expected, the other Treaty signatories demanded answers … and Izvolsky bolted for cover:In order to forestall any such complications [a push by the Young Turks to reclaim the provinces], Aehrenthal moved quickly to prepare the ground for annexation. The Ottomans were bought out of their nominal sovereignty with a handsome indemnity. Much more important were the Russians, upon whose acquiescence the whole project depended. Aehrenthal was a firm believer in the importance of good relations with Russia — as Austrian ambassador in St. Petersburg during the years 1899-1906, he had helped to consolidate the Austro-Russian rapprochement. Securing the agreement of the Russian foreign minister, Alexandr Izvolsky, was easy. The Russians had no objection to the formalization of Austria-Hungary’s status in Bosnia-Herzegovina, provided St. Petersburg received something in return. Indeed it was Izvolsky, with the support of Tsar Nicholas II, who proposed that the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina be exchanged for Austrian support for improved Russian access to the Turkish Straits.

Despite these preparations, Aehrenthal’s announcement of the annexation on 5 October 1908 triggered a major European crisis. Izvolsky denied having reached any agreement with Aehrenthal. He subsequently even denied that he had been advised in advance of Aehrenthal’s intentions, and demanded that an international conference be convened to clarify the status of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In his recent article in History Today, Vernon Bogdanor explains the reaction to this less-than-legal Austro-Hungarian swallowing act:

The annexation […] was a breach of the treaty and of international law. It would have significant consequences. The first was that it made non-Slav rule in Bosnia appear permanent, since the Austro-Hungarian Empire was far more durable than the Ottoman Empire. The annexation was a particular blow to the independent south Slav state of Serbia, which objected. Second, the annexation made the southern Slav issue an international problem, since it involved Serbia’s ally, Russia, which saw itself as the protector of the Slavs. In March 1909 Austria demanded, under threat of war, that Serbia accept the annexation, while Germany told Russia that, in case of war, it would take Austria’s side.

Britain helped persuade Serbia and Russia to back down. The great powers accepted the annexation. The Kaiser, unwisely perhaps, boasted in Vienna in 1910 that he had come to Austria’s side as a ‘knight in shining armour’.

The deciding factor in settling the issue of annexation turned out to be the active involvement of the German government in providing diplomatic pressure on Russia, as Christopher Clark explains:

The issue was resolved only by the “St. Petersburg note” of March 1909, in which the Germans demanded that the Russians at last recognize the annexation and urge Serbia to do likewise. If they did not, Chancellor Bülow warned, then things would “take their course”. This formulation hinted not just at the possibility of an Austrian war on Serbia, but, more importantly, at the possibility that the Germans would release the documents proving Izvolsky’s complicity in the original annexation deal. Izvolsky immediately backed down.

At the time, Aehrenthal took the blame for this fiasco, at least to some degree for his preference for secret deals and understandings. He may have been correct that there was no chance that the other signatories to the Treaty of Berlin would accept the Austrian proposal, but when it all became public, it tarnished his reputation directly and Austria-Hungary’s reputation generally.

Russia hardly came out improved in standing either. As Christopher Clark put it, “the evidence suggests that the crisis took the course that it did because Izvolsky lied in the most extravagant fashion in order to save his job and reputation.” This embarrassing incident at least partially explains why Russia became far more concerned about the fate of the south Slavic populations — having signally failed them once in 1908, Russia could not afford to look like they were going to fail them in future conflicts without forfeiting any influence or control over events in the Balkans. Clark explains the toxic combination of official misinformation, rising political awareness of the Russian middle classes, and the indirect power of the newspapers:

Intense public emotions were invested in Russia’s status as protector of the lesser Slavic peoples, and underlying these in the minds of the key decision-makers was a deepening preoccupation with the question of access to the Turkish Straits. Misled by Izvolksy and fired up by chauvinist popular emotion, the Russian government and public opinion interpreted the annexation as a brutal betrayal of the understanding between the two powers, an unforgivable humiliation and an unacceptable provocation in a sphere of vital interest. In the years that followed the Bosnian crisis, the Russians launched a programme of military investment so substantial that it triggered a European arms race.

Another important question in the wake of the annexation crisis was how Austria-Hungary would placate Serbia. Margaret MacMillan, in The War That Ended Peace outlines the rather small pickings Serbia was offered:

The most difficult issue to settle in the aftermath of the annexation was the question of compensation for Serbia, complicated by the fact that Russia was backing Serbia’s demands and Germany was supporting Austria-Hungary. The most Aehrenthal was prepared to offer Serbia was some economic concessions such as access to a port on the Adriatic, but only if Serbia recognized the annexation and agreed to live on peaceful terms with Austria-Hungary. The Serbian government remained intransigent and, as spring melted the snows in the Balkans, the talk of war mounted again around Europe’s capitals. […] In St. Petersburg, Stolypin, who remained opposed to war, told the British ambassador at the start of March that Russian public opinion was so firmly in support of Serbia that the government would not be able to resist coming to its defense: “Russia would have, in that case, to mobilise, and a general conflagration would then be imminent.”

War was averted in 1908, but the issues that arose (or were exacerbated) during the Bosnian crisis were almost all still significant in 1914. As a dress rehearsal, 1908 went down fairly well: only diplomatic force was exerted, but it showed some of the limits of mere diplomacy and foreshadowed the crisis of July 1914.

August 6, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part eight of a series)

We’re getting closer to the end of the series now … you can catch up to the earlier posts here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, and part seven. The previous post touched on Russia’s disaster in the far east and the dangerous domestic situation it faced after the war. In this post we discover that Italy could be at least as perfidious as “Perfidious Albion”, and that the Balkans are a hell of a place to wage a war.

Italy tips the first domino … in Africa

In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark talks about a war I don’t think I’d ever heard of … an Italian campaign against the Ottoman Empire:

At the end of September 1911, only six months after the foundation of Ujedinjenje ili smrt! [“Union or death!” aka The Black Hand], Italy launched an invasion of Libya. This unprovoked attack one one of the integral provinces of the Ottoman Empire triggered a cascade of opportunistic attacks on Ottoman-controlled territory in the Balkans.

Italy’s attack on the Ottoman Empire was literally planned to steal what is now Libya and incorporate it into a new Italian Empire. Although the formal war was over in thirteen months, indigenous Arabs were still fighting back twenty years later. This attack broke the public-but-informal international understandings about leaving the remaining parts of the Ottoman Empire alone to prevent the risk of great power struggles breaking out. Britain and France had gone to war in 1854 to ensure that Russia did not gain access to the straits and thus a warm-water route to the Mediterranean and the coastlines of southern Europe, but the outcome of both the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War and the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War (and the secret Reinsurance Treaty with Germany) meant that Russia’s hands were largely free as long as Constantinople and the straits were not directly attacked. Italy’s attack broke with that understanding, and could be said to have started the most recent (and also most fatal) scramble for territory in the Balkans.

However, Italy did not act completely outside the norm for a would-be great power: they had an understanding with the French government that was formalized in a secret treaty in 1902 — Italy would not oppose French designs on Tunisia in exchange for French acceptance of Italy’s similar hopes for Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern day Libya). Italy’s attack was only possible because of the anomaly of the British position in Egypt: although still formally part of the Ottoman Empire, day-to-day Egyptian affairs were run by or overseen by British officials. Egypt was militarily occupied, but not a colony of the British Empire, and the country was — in theory — still run by the government of the Khedive. The Ottomans could not move formed bodies of troops through Egypt, and the Ottoman navy did not have the ships to transport them from Anatolia directly to Libya. This gave Italy the opportunity to concentrate against the weaker Ottoman forces.

The otherwise obscure Italo-Turkish War was interesting for several reasons, as the Wikipedia article notes:

Although minor, the war was a significant precursor of the First World War as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the weakened Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the Ottoman Empire before the war with Italy had ended.The Italo-Turkish War saw numerous technological changes, notably the airplane. On October 23, 1911, an Italian pilot, Captain Carlo Piazza, flew over Turkish lines on the world’s first aerial reconnaissance mission, and on November 1, the first ever aerial bomb was dropped by Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti, on Turkish troops in Libya, from an early model of Etrich Taube aircraft. The Turks, lacking anti-aircraft weapons, were the first to shoot down an aeroplane by rifle fire.

It was also in this conflict that the future first president of Turkey and leader of the Turkish War of Independence, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, distinguished himself militarily as a young officer during the Battle of Tobruk.

Although Italy ended up with possession of the disputed land, it did not come easily or cheaply:

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated. The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giovanni Giolitti estimated before the war. This ruined ten years of fiscal prudence.

After the withdrawal of the Ottoman army the Italians could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania, Ghadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913. The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Jihad by the Ottomans and the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania forced the Italians to abandon all occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna, and on the coast of Cyrenaica. The Italian control over much of the interior of Libya remained ineffective until the late 1920s, when forces under the Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani waged bloody pacification campaigns. Resistance petered out only after the execution of the rebel leader Omar Mukhtar on September 15, 1931. The result of the Italian colonisation for the Libyan population was that by the mid-1930s it had been cut in half due to emigration, famine, and war casualties. The Libyan population in 1950 was at the same level as in 1911, approximately 1.5 million in 1911.

The war ended well — at least geographically speaking — for Italy, having gained title not only to Libya but also to the Dodecanese: a group of twelve large and about 150 small islands in the Aegean Sea. The largest and most economically valuable island was Rhodes, which became a useful base for Italian forces for more than 40 years. The treaty ending the Italo-Turkish War required Italy to vacate the islands, but due to both fuzzy wording and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, Italy managed to retain possession.

The Ottoman tide ebbs

The remaining Ottoman territories in Europe were under constant pressure both from external forces (Austria and Russia) and internal linguistic, religious, and cultural separatist movements. Austria preferred to view the separatists as potential new provinces for the Dual Monarchy, while Russia saw the possibility of new independent Russophile political groupings that might allow indirect Russian access to the Mediterranean, bypassing Constantinople (or, perhaps more realistically, additional bases from which to launch an attack against the straits).Italy’s attack was the first domino falling. Christopher Clark writes:

The First World War was the Third Balkan War before it became the First World War. How as this possible? Conflicts and crises on the south-eastern periphery, where the Ottoman Empire abutted Christian Europe, were nothing new. The European system had always accommodated them without endangering the peace of the continent as a whole. But the last years before 1914 saw fundamental change. In the autumn of 1911, Italy launched a war of conquest on an African province of the Ottoman Empire, triggering a chain of opportunistic assaults on Ottoman territories across the Balkans. The system of geopolitical balances that had enabled local conflicts to be contained was swept away. In the aftermath of the two Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, Austria-Hungary faced a new and threatening situation on its south-eastern periphery, while the retreat of Ottoman power raised strategic questions that Russian diplomats and policy-makers found it impossible to ignore.

Margaret MacMillan, in The War That Ended Peace:

It was in the Balkans […] that the greatest dangers were to arise: two wars among its nations, one in 1912 and a second in 1913, nearly pulled the great powers in. Diplomacy, bluff and brinksmanship in the end saved the peace but although Europeans could not know it, they had had a dress rehearsal for the summer of 1914. As they say in the theatre, if that last run-through goes well, the opening night will be a disaster.

The First Balkan War of 1912 — A Pan-Slavic triumph

To some, the Balkans were a comic opera assemblage of exotic uniforms, passionate actors, indecipherable languages, a bit of bloodshed, but no real source of international danger or worry. Margaret MacMillan explains that much happened beneath the surface of the above-ground culture: much that portended danger to the entire region and beyond.

To the rest of Europe the Balkan states were something of a joke, the setting for tales of romance such as the Prisoner of Zenda or operettas (Montenegro was the inspiration for the The Merry Widow), but their politics were deadly serious — and frequently deadly with terrorist plots, violence and assassinations. In 1903 King Peter’s unpopular predecessor as King of Serbia and his equally unpopular wife had been thrown from the windows of the palace and their corpses hacked to pieces. […] The growth of national movements had welded peoples together but it had also divided Orthodox from Catholic or Muslim, Albanians from Slaves, and Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, Bulgarians or Macedonians from each other. While the peoples of the Balkans had coexisted and intermingled, often for long periods of peace through the centuries, the establishment of national states in the nineteenth century had too often been accompanied by burning of villages, massacres, expulsions of minorities and lasting vendettas.

Politicians who had ridden to power by playing on nationalism and with promises of national glory found they were in the grip of forces they could not always control. Secret societies, modelling themselves on an eclectic mix which included Freemasonry, the underground Carbonari, who had worked for Italian unity, the terrorists who more recently had frightened much of Europe, and old-style banditry, proliferated throughout the Balkans, weaving their way into civilian and military institutions of the states.

In addition to the ethnic, proto-national, cultural, and religious aspects of Balkan conflict, it was also an inter-generational conflict:

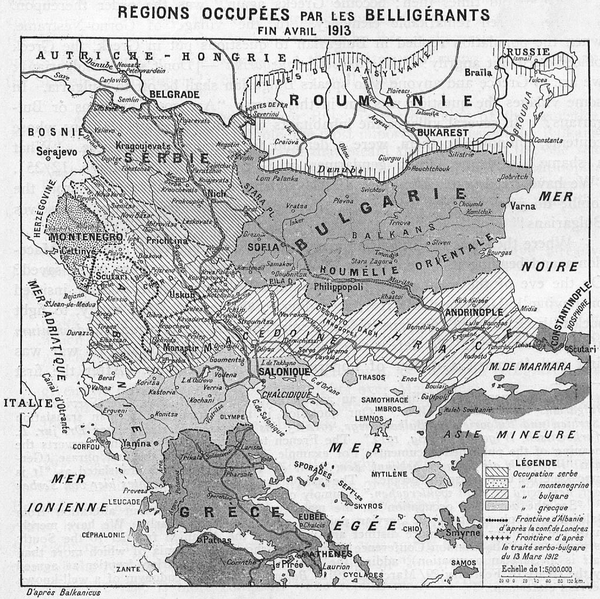

Comic opera states or not, they proved to be more than a match for their Ottoman overlords. Taking advantage of the Italian attack on Libya, Serbia allied with Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro to invade and capture much of the Balkan peninsula, stopping just a few miles outside Constantinople. The First Balkan War triggered vast population shifts, as nearly half a million Muslims fled from the conquered territory to escape religious persecution (and many thousands died through privation, disease, and starvation. Between the actual combat between military forces, forced evacuations, and the early use of genocidal policies, several million people were forced out of their homes and moved at gunpoint to wherever the armed groups wanted them to go. Cultural patterns nearly a millennia old were uprooted and dispersed to suit the tastes of local warlords and jumped-up military leaders.The younger generation who were attracted to the secret societies were often more extreme than their elders and frequently at odds with them. “Our fathers, our tyrants,” said a Bosnian radical nationalist, “have created this world on their model and are now forcing us to live in it.” The young members were in love with violence and prepared to destroy even their own traditional values and institutions in order to build the new Greater Serbia, Bulgaria, or Greece. (Even if they had not read Nietzsche, which many of them had, they too had heard that God was dead and that European civilization must be destroyed in order to free humankind.) In the last years before 1914, the authorities in the Balkan states either tolerated or were powerless to control the activities of their own young radicals who carried out assassinations and terrorist attacks on Ottoman or Austrian-Hungarian official as oppressors of the Slavs, on their own leaders whom they judged to be insufficiently devoted to the nationalist cause, or simply on ordinary citizens who happened to be in the wrong religion or the wrong ethnicity in the wrong place.

And there it might have ended, but the unexpectedly successful campaign by the Balkan League left just a few too many loose ends, which almost immediately led to conflict among the victorious allies. Since I’ve already tipped you to the fact that there was more than one Balkan War, you probably won’t be surprised to find that the Second Balkan War happened quite soon after the first one. But that’s a tale for another day.

July 29, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part two of a series)

Yesterday, I posted the first part of this series. Today, I’m dragging you a lot further back in time than you probably expected, because it’s difficult to understand why Europe went to war in 1914 without knowing how and why the alliances were created. It’s not immediately clear why the two alliance blocks formed, as the interests of the various nations had converged and diverged several times over the preceding hundred years.

Let me take you back…

To start sorting out why the great powers of Europe went to war in what looks remarkably like a joint-suicide pact at the distance of a century, you need to go back another century in time. At the end of the Napoleonic wars, the great powers of Europe were Russia, Prussia, Austria, Britain, and (despite the outcome of Waterloo) France. Britain had come out of the war in by far the best economic shape, as the overseas empire was relatively untroubled by conflict with the other European powers (with one exception), and the Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the world. France was an economic and demographic disaster area, having lost so many young men to Napoleon’s recruiting sergeants and the bureaucratic demands of the state to subordinate so much of the economy to the support of the armies over more than two decades of war, recovery from war, and preparation for yet more war. In spite of that, France recovered quickly and soon was able to reclaim its “rightful” position as a great power.

Dateline: Vienna, 1814

The closest thing to a supranational organization two hundred years ago was the Concert of Europe (also known as the Congress System), which generally referred to the allied anti-Napoleonic powers. They met in Vienna in 1814 to settle issues arising from the end of Napoleon’s reign (interrupted briefly but dramatically when Napoleon escaped from exile and reclaimed his throne in 1815). It worked well enough, at least from the point of view of the conservative monarchies:

The age of the Concert is sometimes known as the Age of Metternich, due to the influence of the Austrian chancellor’s conservatism and the dominance of Austria within the German Confederation, or as the European Restoration, because of the reactionary efforts of the Congress of Vienna to restore Europe to its state before the French Revolution. It is known in German as the Pentarchie (pentarchy) and in Russian as the Vienna System (Венская система, Venskaya sistema).

The Concert was not a formal body in the sense of the League of Nations or the United Nations with permanent offices and staff, but it provided a framework within which the former anti-Bonapartist allies could work together and eventually included the restored French Bourbon monarchy (itself soon to be replaced by a different monarch, then a brief republic and then by Napoleon III’s Second Empire). Britain after 1818 became a peripheral player in the Concert, only becoming active when issues that directly touched British interests were being considered.

The Concert was weakened significantly by the 1848-49 revolutionary movements across Europe, and its usefulness faded as the interests of the great powers became more focused on national issues and less concerned with maintaining the long-standing balance of power.

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

[…]

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).

The 1859 unification of Italy created new problems for Austria (not least the encouragement of agitation among ethnic and linguistic minorities within the empire), while the rise of Prussia usurped the traditional place of Austria as the pre-eminent Germanic power (the Austro-Prussian War). The 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War destroyed Napoleon III’s Second Empire and allowed the King of Prussia to become the Emperor (Kaiser) of a unified German state.

Russia’s search for a warm water port

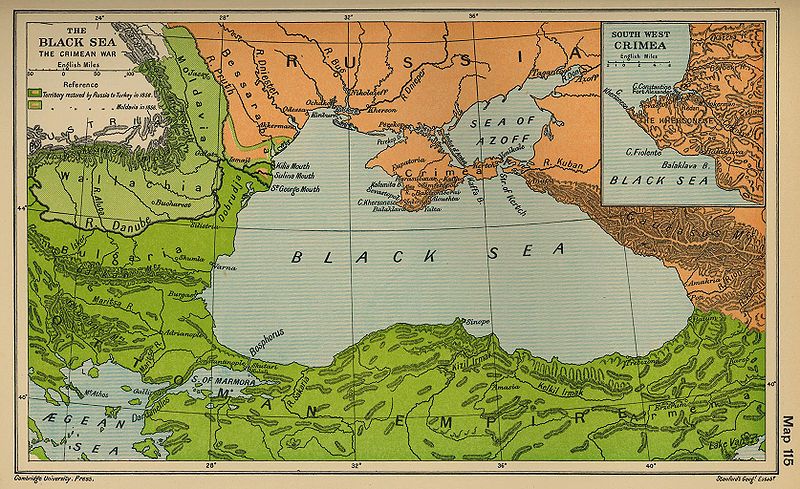

Russia’s not-so-secret desire to capture or control Constantinople and the access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean was one of the political and military constants of the nineteenth century. The Ottoman Empire was the “sick man of Europe”, and few expected it to last much longer (yet it took a world war to finally topple it). The other great powers, however, were not keen to see Russia expand beyond its already extensive borders, so the Ottomans were propped up where necessary. The unlikely pairing of British and French interests in this regard led to the 1853-6 Crimean War where the two former enemies allied with the Ottomans and the Kingdom of Sardinia to keep the Russians from expanding into Ottoman territory, and to de-militarize the Black Sea.

The Black Sea in 1856 with the territorial adjustments of the Congress of Paris marked (via Wikipedia)

Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck talks with the captive Napoleon III after the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

In the wake of Napoleon III’s fall, France declared that they were no longer willing to oppose the re-introduction of Russian forces on and around the Black Sea. Britain did not feel it could enforce the terms of the 1856 treaty unaided, so Russia happily embarked on building a new Black Sea fleet and reconstructing Sebastopol as a fortified fleet base.

Twenty years after the Crimean War, the Russians found more success against the Ottomans, driving them out of almost all of their remaining European holdings and establishing independent or quasi-independent states including Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, with at least some affiliation with the Russians. A British naval squadron was dispatched to ensure the Russians did not capture Constantinople, and the Russians accepted an Ottoman truce offer, followed eventually by the Treaty of San Stefano to end the war. The terms of the treaty were later reworked at the Congress of Berlin.

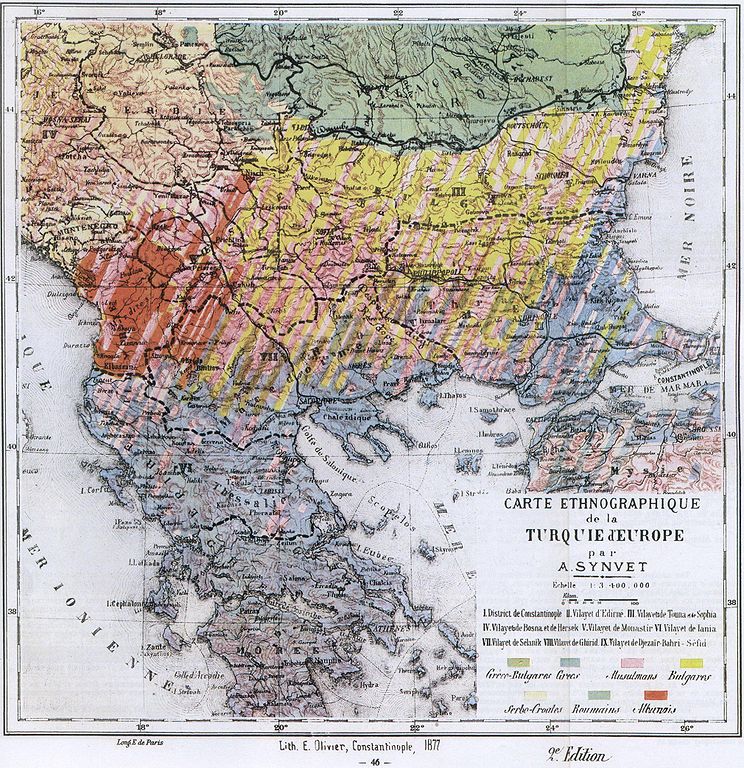

Other territorial changes resulting from the war was the restoration of the regions of Thrace and Macedonia to Ottoman control, the acquisition by Russia of new territories in the Caucasus and on the Romanian border, the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar (but not yet annexed to the empire), and British possession of Cyprus. The new states and provinces addressed a few of the ethnic, religious, and linguistic issues, but left many more either no better or worse than before:

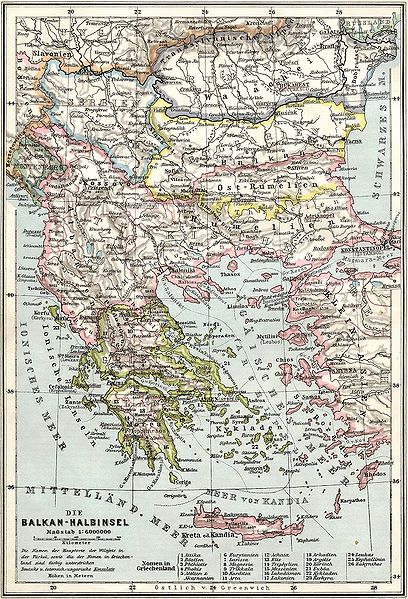

An ethnographic map of the Balkans published in Carte Ethnographique de la Turquie d’Europe par A. Synvet, Lith. E Olivier, Constantinople 1877. (via Wikipedia)

The end of the second post and we’re still in the 1870s … more to come over the next few days.

April 16, 2014

Russia’s long and brutal relationship with Crimea

In History Today, Alexander Lee talks about the historical attitude of Russia toward the Crimean peninsula and some of the terrible things it has done to gain and retain control over the region:

… Russia’s claim to Crimea is based on its desire for territorial aggrandizement and – more importantly – on history. As Putin and Akysonov are keenly aware, Crimea’s ties to Russia stretch back well back into the early modern period. After a series of inconclusive incursions in the seventeenth century, Russia succeeded in breaking the Ottoman Empire’s hold over Crimea with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), before formally annexing the peninsula in 1784. It immediately became a key factor in Russia’s emergence as a world power. Offering a number of natural warm-water harbours, it gave access to Black Sea trade routes, and a tremendous advantage in the struggle for the Caucasus. Once gained, it was not a prize to be willingly surrendered, and the ‘Russianness’ of Crimea quickly became a cornerstone of the tsars’ political imagination. When a spurious dispute over custody of Christian sites in the Holy Land escalated into a battle for the crumbling remnants of the Ottoman Empire in 1853, Russia fought hard to retain its hold over a territory that allowed it to threaten both Constantinople and the Franco-British position in the Mediterranean. Almost a century later, Crimea was the site of some of the bitterest fighting of the Second World War. Recognising its military and economic importance, the Nazis launched a brutal attempt to capture the peninsula as a site for German resettlement and as a bridge into southern Russia. And when it was eventually retaken in 1944, the reconstruction of Sevastopol – which had been almost completely destroyed during a long and bloody siege – acquired tremendous symbolic value precisely because of the political and historical importance of the region. Even after being integrated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and – later – acknowledged as part of an independent Ukraine after the fall of the USSR, Crimea’s allure was so powerful that the new Ukrainian President, Leonid Kraychuk, claimed that Russia’s attempts to assert indirect control of the peninsula betrayed the lingering force of an ‘imperial disease’.

[…]

The non-Russian population of Crimea was to suffer further even worse under the Soviet Union, and between 1921 and 1945, two broad phases of persecution devastated their position in the peninsula. The first was dominated by the fearsome effects of Stalinist economic policy. In keeping with the centralised aims of the First Five-Year Plan (1928-32), Crimean agricultural production was collectivised, and reoriented away from traditional crops such as grain. On top of this, bungling administrators imposed impossibly high requisition quotas. The result was catastrophic. In 1932, a man-made famine swept through the peninsula. Although agronomists had warned their political masters of the danger from the very beginning, the Moscow leadership did nothing to relieve the situation. Indeed, quite the reverse. As starvation began to take hold, Stalin not only prosecuted those who attempted to collect left-over grain from the few remaining collectivised farms producing grain, but also hermetically sealed regions afflicted by shortages. He was using the famine to cleanse an ethnically diverse population. A true genocide, the Holodmor (‘extermination by hunger’) – as this artificial famine is known – killed as many as 7.5 million Ukrainians, including tens of thousands of Crimeans. And when it finally abated, Stalin took the opportunity to fill the peninsula with Russians, such that by 1937, they accounted for 47.7% of the population, compared to the Tatars’ 20.7%.

The second phase – covering the period between 1941 and 1945 – compounded the terrible effects of the Holodmor. On its own, the appalling casualties caused by the savage battle for Crimea would have decimated the peninsula. Some 170,000 Red Army troops were lost in the struggle, and the civilian population suffered in equal proportion. But after the Soviet Union regained control, the region was subjected to a fresh wave of horror. Accusing the Tatars of having collaborated with the Nazis during the occupation, Stalin had the entire population deported to Central Asia on 18 May 1944. The following month, the same fate was meted out to other minorities, including Greeks and Armenians. Almost half of those subject to deportation died en route to their destination, and even after they were rehabilitated under Leonid Brezhnev, the Tatars were prohibited from returning to Crimea. Their place was taken mostly by ethnic Russians, who by 1959 accounted for 71.4% of the population, and – to a lesser extent – Ukrainians.