Scenic Routes to the Past

Published Jul 12, 2024This second part of my survey of Herculaneum explores some of the site’s incredibly well-preserved houses.

(more…)

November 8, 2024

Highlights of Herculaneum (Part II)

November 7, 2024

Highlights of Herculaneum (Part I)

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published Jul 9, 2024An introduction to Herculaneum, buried and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. This video surveys the site and some of its public monuments. Part II explores Herculaneum’s incredibly well-preserved houses.

Check out my other channels, @toldinstone and @toldinstonefootnotes

October 27, 2024

Reading the Herculaneum Papyri

Toldinstone Footnotes

Published Jul 5, 2024On this episode of the Toldinstone Podcast, Dr. Federica Nicolardi and I discuss the challenges of reading scrolls charred and buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Chapters:

00:00 Discovery of the scrolls

03:23 Opened and unopened

05:17 How to handle charred papyrus

09:11 New texts

13:17 Philodemus of Gadara

16:04 Epicurean philosophy

20:20 The library in the Villa of the Papyri

24:05 The Vesuvius Challenge

25:56 Progress so far …

28:44 The newest text

30:06 What comes next

34:20 What’s still buried?

October 26, 2024

Secrets of the Herculaneum Papyri

toldinstone

Published Jul 5, 2024The Herculaneum papyri, scrolls buried and charred by Vesuvius, are the most tantalizing puzzle in Roman archaeology. I recently visited the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples, where most of the papyri are kept, and discussed the latest efforts to decipher the scrolls with Dr. Federica Nicolardi.

My interview with Dr. Nicolardi: https://youtu.be/gs1Z-YN1aQMChapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:40 Opening the scrolls

1:47 A visit to the library

2:38 A papyrologist at work

4:00 The Vesuvius Challenge

4:46 What the scrolls say

5:40 Contents of the unopened scrolls

6:28 The other library

7:12 An interview with Dr. Nicolardi

(more…)

September 8, 2024

Ancient sources

In writing history from the early modern period onward, it’s a common problem to have too many sources for a given event so that it’s the job of the historian to (carefully, one hopes) select the ones that hew closer to the objective truth. In ancient history, on the other hand, we have so few sources to rely upon that it’s a luxury to have multiple accounts of a given event from which to choose:

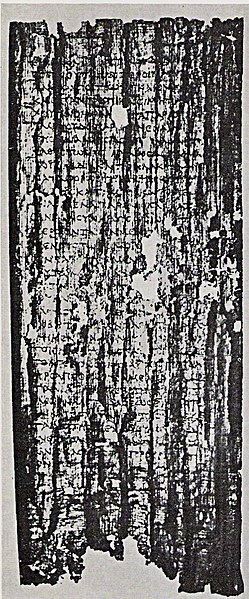

Unrolled papyrus scroll recovered from the Villa of the Papyri.

Picture published in a pamphlet called “Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri” by Amedeo Maiuri in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

We used to play this game in graduate school: find one, lose one. Find one referred to finding a lost ancient text, something that we know existed at one time because other ancient sources talk about it, but which has been lost to the ages. What if someone was digging somewhere in Egypt and found an ancient Greco-Roman trash dump with a complete copy of a precious text – which one would we wish into survival? Lose one referred to some ancient text we have, but we would give up in some Faustian bargain to resurrect the former text from the dead. Of course there is a bit of the butterfly effect; that’s what made it fun. As budding classicists, we grew up in an academic world where we didn’t have A, but did have B. How different would classical scholarship be if that switched? If we had had A all along, but never had B? For me, the text I always chose to find was a little-known pamphlet circulated in the late fourth century by a deposed Spartan king named Pausanias. It’s one of the few texts about Sparta written by a Spartan while Sparta was still hegemonic. I always lost the Gospel of Matthew. It’s basically a copy of Mark, right down to the grammar and syntax. Do we really need two?

What would you choose? Consider that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are only two of the poems that make up the eight-part Epic Cycle. Or that Aristotle wrote a lost treatise on comedy, not to mention his own Socratic dialogues that Cicero described as a “river of gold”. Or that only eight of Aeschylus’s estimated 70 plays survive. Even the Hebrew Old Testament refers to 20 ancient texts that no longer exist. There are literally lost texts that, if we had them, would in all likelihood have made it into the biblical canon.

The problem is more complex than the fact that many texts were lost to the annals of history. Most people just see the most recent translation of the Iliad or works of Cicero on the shelf at a bookstore, and assume that these texts have been handed down in a fairly predictable way generation after generation: scribes faithfully made copies from ancient Greece through the Middle Ages and eventually, with the advent of the printing press, reliable versions of these texts were made available in the vernacular of the time and place to everyone who wanted them. Onward and upward goes the intellectual arc of history! That’s what I thought, too.

But the fact is, many of even the most famous works we have from antiquity have a long and complicated history. Almost no text is decoded easily; the process of bringing readable translations of ancient texts into the hands of modern readers requires the cooperation of scholars across numerous disciplines. This means hours of hard work by those who find the texts, those who preserve the texts, and those who translate them, to name a few. Even with this commitment, many texts were lost – the usual estimate is 99 percent – so we have no copies of most of the works from antiquity.1 Despite this sobering statistic, every once in a while, something new is discovered. That promise, that some prominent text from the ancient world might be just under the next sand dune, is what has preserved scholars’ passion to keep searching in the hope of finding new sources that solve mysteries of the past.

And scholars’ suffering paid off! Consider the Villa of the Papyri, where in the eighteenth century hundreds, if not thousands, of scrolls were discovered carbonized in the wreckage of the Mount Vesuvius eruption (79 AD), in a town called Herculaneum near Pompeii. For over a century, scholars have hoped that future science might help them read these scrolls. Just in the last few months – through advances in computer imaging and digital unwrapping – we have read the first lines. This was due, in large part, to the hard work of Dr. Brent Seales, the support of the Vesuvius Challenge, and scholars who answered the call. We are now poised to read thousands of new ancient texts over the coming years.

[…]

Now let’s look at a text with a very different history, the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia. The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia is the name given to a group of papyrus fragments found in 1906 at the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus, modern Al-Bahnasa, Egypt (about a third of the way down the Nile from Cairo to the Aswan Dam). These fragments were found in an ancient trash heap. They cover Greek political and military history from the closing years of the Peloponnesian War into the middle of the fourth century BC. In his Hellenica, Xenophon covers the exact same time frame and many of the same events.2 Both accounts pick up where Thucydides, the leading historian of the Peloponnesian War (fought between Athens and Sparta in the fifth century BC), leaves off.

While no author has been identified for the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, the grammar and style date the text to the era of the events it describes. This is a recovered text, meaning it was completely lost to history and only discovered in the early twentieth century. Here, the word discovered is appropriately used, as this was not a text that was renowned in ancient times. No ancient historians reference it, and it did not seem to have a lasting impact in its day. What is dismissible in the past is forgotten in the present. The text is written in Attic Greek. This implies that whoever wrote the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia must have been an elite familiar enough with the popular Attic style to replicate it, and likely intended for the history to equal those of Thucydides and Xenophon. There were other styles available to use at the time but Attic Greek was the style of both the aforementioned historians, as well as the writing style of the elite originating in Athens. Any history not written in Attic would have been seen as inferior. Given that the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was lost for thousands of years, it would seem our author failed in his endeavor to mirror the great historians of classical Greece.

The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia serves as a reminder that the modern discovery of ancient texts continues. Many times, these are additional copies of texts we already have. This is not to say these copies are not important. Such was the case of the aforementioned Codex Siniaticus, discovered by biblical scholar Konstantin von Tischendorf in a trash basket, waiting to be burned, in a monastery near Mount Sinai in Egypt in 1844. Upon closer examination, Tischendorf discovered this “trash” was in fact a nearly complete copy of the Christian Bible, containing the earliest complete New Testament we have. One major discrepancy is that the famous story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery – from which the oft-quoted passage “let he who is without sin cast the first stone” originates – is not found in the Codex Sinaiticus.

Yet, sometimes something truly new to us, that no one has seen for thousands of years, is unearthed. In the case of the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, no one seemingly had looked at this text for at least 1,500 years, maybe more. This demonstrates that there is always the possibility that buried in some ancient scrap heap in the desert might be a completely new text that, once published for wider scholarship, greatly increases our knowledge of the ancients.

How does this specific text increase our knowledge? Bear in mind that before this period of Greek history, we have just one historian per era. Herodotus is the only source we have for the Greco-Persian Wars (480–479), and the aforementioned Thucydides picks up from there and quickly covers the political climate before beginning his history proper with the advent of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. But Thucydides’s history is unfinished – one ancient biography claims he was murdered on his way back to Athens around 404 BC. Many doubt this, citing evidence that he lived into the early fourth century BC. Either way, his narrative ends abruptly. Xenophon picks it up from there, and later we get a more brief history of this period from Diodorus, who wrote much later, between 60 and 30 BC. While describing the same time frame and many of the same events, these two sources vary widely in their descriptions of certain events. In some cases, they make mutually exclusive claims. One historian must have got it wrong.

For centuries, Xenophon’s account was the preferred text. That is not to say Diodorus’s history was dismissed, but when the two accounts were in conflict, Xenophon’s testimony got the nod. This was partially because Xenophon actually lived during the times he wrote about, whereas Diodorus lived 200 years after these events in Greek history. Consider if there were two conflicting accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg from two different historians: one actually lived during and participated in the war, while the other was a twenty-first century scholar living 150 years after the events he describes. They disagree on key elements of the battle. Who do you believe? This was precisely the case with Xenophon and Diodorus. Yet, once the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was published, it corroborated Diodorus’s history far more than that of Xenophon, forcing historians to reconsider their bias toward the older of the two accounts.

1. You can find a list of texts we know that we have lost at the Wikipedia page “Lost literary work“.

2. “Oxyrhynchus Historian”, in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. MC Howatson (Oxford University Press, 2011).

February 21, 2024

“There’s a moral imperative to go dig out that villa … It could be the greatest archaeological treasure on earth”

In City Journal, Nicholas Wade discusses the technical side of the ongoing attempts to read one of the Herculaneum scrolls:

A computer scientist has labored for 21 years to read carbonized ancient scrolls that are too brittle to open. His efforts stand at last on the brink of unlocking a vast new vista into the world of ancient Greece and Rome.

Brent Seales, of the University of Kentucky, has developed methods for scanning scrolls with computer tomography, unwrapping them virtually with computer software, and visualizing the ink with artificial intelligence. Building on his methods, contestants recently vied for a $700,000 prize to generate readable sections of a scroll from Herculaneum, the Roman town buried in hot volcanic mud from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

The last 15 columns — about 5 percent—of the unwrapped scroll can now be read and are being translated by a team of classical scholars. Their work is hard, as many words are missing and many letters are too faint to be read. “I have a translation but I’m not happy with it,” says a member of the team, Richard Janko of the University of Michigan. The scholars recently spent a session debating whether a letter in the ancient Greek manuscript was an omicron or a pi.

[…]

Seales has had to overcome daunting obstacles to reach this point, not all of them technical. The Italian authorities declined to make any of the scrolls available, especially to a lone computer scientist with no standing in the field. Seales realized that he had to build a coalition of papyrologists and conservationists to acquire the necessary standing to gain access to the scrolls. He was eventually able to x-ray a Herculaneum scroll in Paris, one of six that had been given to Napoleon. To find an x-ray source powerful enough to image the scroll without heating it, he had to buy time on the Diamond particle accelerator at Harwell, England.

In 2009, his x-rays showed for the first time the internal structure of a scroll, a daunting topography of a once-flat surface tugged and twisted in every direction. Then came the task of writing software that would trace the crumpled spiral of the scroll, follow its warped path around the central axis, assign each segment to its right position on the papyrus strip, and virtually flatten the entire surface. But this prodigious labor only brought to light a more formidable problem: no letters were visible on the x-rayed surface.

Seales and his colleagues achieved their first notable success in 2016, not with Napoleon’s Herculaneum scroll but with a small, charred fragment from a synagogue at the En-Gedi excavation site on the shore of the Dead Sea. Virtually unwrapped by the Seales software, the En-Gedi scroll turned out to contain the first two chapters of Leviticus. The text was identical to that of the Masoretic text, the authoritative version of the Hebrew Bible — and, at nearly 2,000 years old, its earliest instance.

The ink used by the Hebrew scribes was presumably laden with metal, and the letters stood out clearly against their parchment background. But the Herculaneum scroll was proving far harder to read. Its ink is carbon-based and almost impossible for x-rays to distinguish from the carbonized papyrus on which it is written. The Seales team developed machine-learning programs — a type of artificial intelligence — that scanned the unrolled surface looking for patterns that might relate to letters. It was here that Seales found use for the fragments from scrolls that earlier scholars had destroyed in trying to open them. The machine-learning programs were trained to compare a fragment holding written text with an x-ray scan of the same fragment, so that from the statistical properties of the papyrus fibers they could estimate the probability of the presence of ink.

February 9, 2024

The (so-far limited) ability to read the Herculaneum Papyri may vastly increase our knowledge about the Roman world

Colby Cosh on the achievement of the three young researchers who were awarded the Vesuvius Challenge prize earlier this month, and what it might mean for classicists and other academics:

On Monday morning, Farritor and two other young Vesuvius Challenge notables, Youssef Nader and Julian Schillinger, were announced as winners of the grand prize. Nader and Schillinger had, like Farritor, already won Vesuvius Challenge prizes for smaller technical discoveries, and Nader had in fact been a mere heartbeat behind Farritor in producing the same “porphyras” from the same scan. After Farritor nabbed his US$40,000 “first letters” prize, the three decided to combine their efforts to net the big fish.

The result is a text that represents about five per cent of one of the thousands of scrolls recovered — and there may be more not yet recovered — from the Villa of the Papyri. The enormous villa was owned by an unknown Roman notable, but there are clues that one of its librarians was the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, who lived from around 110 to 35 BC. Until his identity was connected with the library, Philodemus did not receive too much attention even from classicists. But the Vesuvius Challenge efforts have now yielded fragments of what has to be an Epicurean text — one which discusses the delights of music and food, and condemns an unnamed adversary, possibly a Stoic, for failing to give a philosophical account of sensual pleasure.

The recovery of dozens more of the works of Philodemus would be — one might now say “will be” — a world-changing event for the classics. We know Philodemus was close to Calpurnius Piso (101-43 BC), the father-in-law of Julius Caesar and a likely owner of the doomed villa. He almost certainly had a front-row seat for the prelude to the end of the Roman Republic. We know he wrote works on religion, on natural philosophy and on history: even his thoughts on music and poetry would be of marked interest.

But nobody knows what else, what copies of older works, may be lurking in Philodemus’s library. At this moment antiquarians know the titles of dozens of lost plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides and Aristophanes; we are missing major works of Aristotle and Euclid and Archimedes and Eratosthenes. We know that Sulla wrote his memoirs and that Cato the Elder wrote a seven-book history of Rome. Any of these old writings, or others of equal significance, may materialize suddenly out of oblivion now, thanks to the Vesuvius Challenge. It’s an impressive triumph for the idea of prize-giving as an approach to solving scientific problems, and the news release from the challenge offers a discussion of what the funding team got right and where the project will go next.

February 5, 2024

The Vesuvius Challenge prize has been awarded!

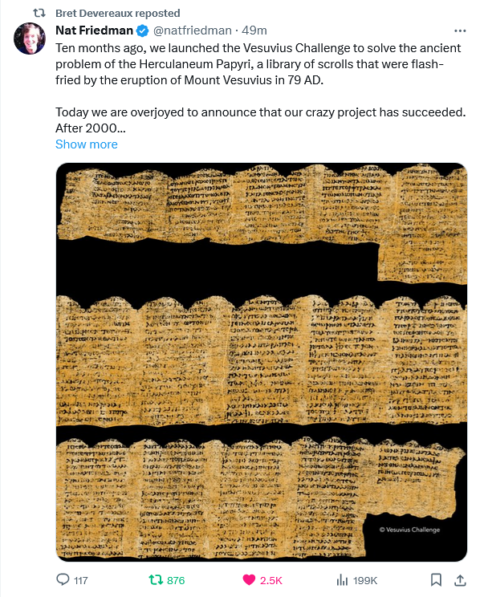

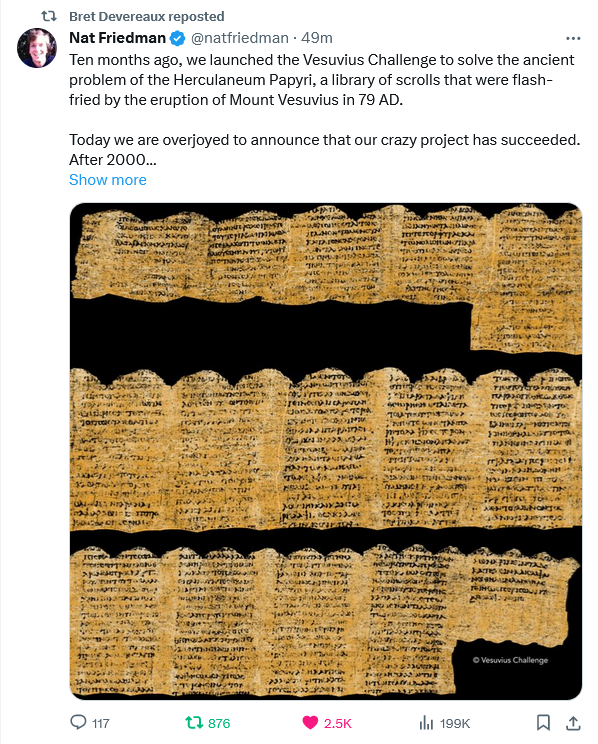

Scrolling through Twit-, er, I mean “X” this morning brought me this amazing piece of news for classical scholars:

We received many excellent submissions for the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize, several in the final minutes before the midnight deadline on January 1st.

We presented these submissions to the review team, and they were met with widespread amazement. We spent the month of January carefully reviewing all submissions. Our team of eminent papyrologists worked day and night to review 15 columns of text in anonymized submissions, while the technical team audited and reproduced the submitted code and methods.

There was one submission that stood out clearly from the rest. Working independently, each member of our team of papyrologists recovered more text from this submission than any other. Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing the Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85% of characters recoverable. This was not a given: most of us on the organizing team assigned a less than 30% probability of success when we announced these criteria! And in addition, the submission includes another 11 (!) columns of text — more than 2000 characters total.

The results of this review were clear and unanimous: the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize of $700,000 is awarded to a team of three for their excellent submission. Congratulations to Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger!

Much more information at the Vesuvius Challenge site.

October 17, 2023

An appropriate task for AI – reading the Herculaneum scrolls

Colby Cosh discusses the possibility of finally being able to read the carbonized scolls found in the buried remains of a wealthy Roman’s country villa in 1750:

Unrolled papyrus scroll recovered from the Villa of the Papyri.

Picture published in a pamphlet called “Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri” by Amedeo Maiuri in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

From the standpoint of fragile human life, a volcanic eruption is the worst possible thing that can happen anywhere in your general vicinity, up to and probably including the detonation of a nuclear weapon.

It goes without saying that pyroclastic flows are also bad for animals or buildings or vegetation … or documents. And yet: as a consequence of the eruption of Vesuvius, there exists a near-complete library of papyrus scrolls retrieved from the buried ruins of a splendid Roman villa.

The “Villa of the Papyri” in Herculaneum was found in 1750 by farmers and was quickly subjected to archeological excavation, an art then in its infancy.

These scrolls, which today number about 1,800 in all, are often described as the only known library to have physically survived from antiquity. The problem, of course, is that they have all been burned literally to a crisp, with only a few easily readable fragments here and there.

The incinerated scrolls are so sensitive that they tend to explode into a cloud of ash at the slightest touch. Occasional attempts to unravel the scrolls — which were rolled very tightly for storage in the first place — have been made over the past 300 years; the chemist Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829), for example, gave it a shot using newfangled stuff called chlorine. But none of these projects ever came especially close to success, and they typically involved destruction of some of the “books” in the library.

In recent years 3D imaging techniques for “reading” documents like this in a non-invasive way have been making great headway. The leader in the field is a University of Kentucky computer scientist named Brent Seales, who in 2015 led efforts to read a fragile, desiccated Hebrew Bible parchment scroll dating to the third or fourth century AD.

The text was from the book of Leviticus, and proved to be a letter-for-letter match with the Torah of today — which is a disappointment to scholars from one point of view, and a finding of awesome significance from another. (It goes without saying that this scroll came from the territory of Israel, near a kibbutz: this is a fact that would, in any other political context, be regarded as a supreme affirmation of indigeneity.)

Seales has been able to “unroll” some Herculaneum scrolls and detect the presence of inks using CT scanning, but reading the pages is a profound challenge. Roman ink was carbon-based, meaning researchers are trying to “read” traces of carbon on carbonized pages rolled up into three dimensions.