Fortissax contrasts Canadians and Americans ethnically, culturally, and historically. Here he discusses Anglo-Canadians and French-Canadians:

To understand Canada, you must first understand its foundations.

Canada is a breakaway society from the United States, like the United States was a breakaway society from the British Empire. You might even argue that Britain represented a thesis, America an antithesis, and Canada the synthesis.

Anglo-Canadians

Anglo-Canadians are descendants of the Loyalists from the American Revolution. They were North Americans, not British transplants, as depicted in American propaganda like Mel Gibson’s The Patriot. They shared the same pioneering and independent spirit as their Patriot counterparts. All were English “Yeoman” or free men. American history from the Mayflower to 1776 is also Canadian history. It is why both nations share Thanksgiving. Some historians have identified the American Revolution as an English civil war, and this is a fairly accurate assessment.

The United States’ founding philosophy was rooted in liberalism; it is a proposition nation based on creed over blood, shaped by Enlightenment thinkers like Edmund Burke and John Locke, now considered “conservative”. American revolutionaries embraced ideals of meritocracy, individualism, property rights, capitalism, free enterprise, republicanism, and democracy, which empowered the emerging middle class.

Anglo-Canada’s founding philosophy is British Toryism, emerging as a traditionalist and reactionary force in direct response to the American Revolution. During the revolution, many Loyalists had their private property seized or redistributed, suffered beatings in the streets, and in the worst cases, faced public executions or the infamous punishment of tar and feathering. Canadian philosopher George Grant, who is considered the father of Anglo-Canadian nationalism, traced their roots to Elizabethan-era Anglican theologian Richard Hooker.

Canada’s motto, Peace, Order, and Good Government (POGG), reflects a philosophy in stark contrast to the American ideal of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Anglo-Canadians valued God, King, and Country, emphasizing public morality, the common good, and Tory virtues like noblesse oblige — the expectation and obligation of elites to act benevolently within an organic hierarchy. While liberty was important, it was never to come at the expense of order. Canadian conservatism before the 1960s was not a variation of liberalism, as in the U.S., but a much older, European, and genuinely traditional ideology focused on community, public order, self-restraint, and loyalty to the state — values embedded in Canada’s founding documents.

Section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, empowers Parliament to legislate for the “peace, order, and good government” of Canada, giving rise to Crown corporations like Ontario Hydro, the CBC, and Canadian National Railway — state-owned enterprises. Canada’s tradition of mixed economic policies is often misunderstood by Americans as socialism, communism, or totalitarianism. These state-owned enterprises have historical precedents, such as state-controlled factories during Europe’s industrial revolution, often run by landed nobility. Going further back, state-owned mines in ancient Athens and Roman Empire granaries also exemplify this model, which cannot be simplistically labeled as “Islamofascist communism” — a mischaracterization of anything not aligned with liberalism by many Americans, and increasingly many populist Canadians.

It is also a lesser-known historical fact that Canada was almost ennobled into a kingdom rather than a dominion. This idea was suggested by Thomas D’Arcy McGee, a prominent Irish-Canadian politician, journalist, and one of the Fathers of Confederation. Deeply involved in the creation of Canada as a nation, McGee proposed in the 1860s that Canada could be formed as a monarchy with a hereditary nobility, possibly with a viceroyal king, likely a son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He believed this would provide stability and continuity to the fledgling nation. While this idea was not realized, its influence can be seen in the entrenched elites of Canada, who, in a sense, became an unofficial aristocracy.

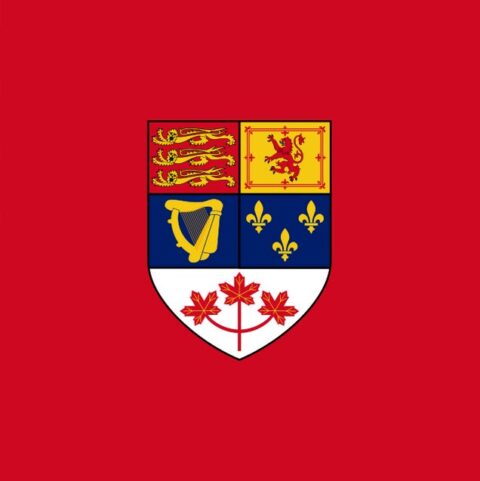

An element of Canada’s conservative origins can also be found in its use of traditional British and French heraldry. Every province, for example, has a medieval-style coat of arms, often displayed on its flag, which reinforces this connection to the old-world traditions McGee sought to preserve.

McGee’s vision was rooted in his belief in the importance of monarchical institutions and his desire to strengthen Canada’s bond with the British Crown while fostering a distinct Canadian identity. He argued that ennobling Canada would give the country legitimacy and elevate it in the eyes of Europe and the wider world.

French-Canadians

French Canada, with Quebec as its largest and most influential component, has a distinct history shaped by its French colonial roots. Quebec was primarily settled by French colonists, and its unique culture and identity have evolved over the centuries, heavily influenced by Catholicism and monarchical traditions.

The Jesuits and other Catholic organizations played a pivotal role in shaping early French Canadian society. They not only spread Christianity but also laid the foundation for Quebec’s social and cultural identity. The Jesuits, part of the Society of Jesus, were among the first Catholic missionaries to arrive in New France. Invited by Samuel de Champlain, the founder of Quebec, in 1611, they helped convert Indigenous populations to Catholicism but often remained separate from them. By 1625, they had established missions among various Indigenous nations, including the Huron, Algonquin, and Iroquois.

Unlike France, Quebec bypassed the upheavals of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. Isolated from the homeland, the Catholic Church in Quebec consolidated its power, and French colonists faced the threat of extinction due to their initially low numbers, particularly during the one-hundred-year war with the Iroquois. This struggle only strengthened their resolve. Over time, this foundation gave rise to Clerico-Nationalism, particularly exemplified by figures like Abbé Lionel Groulx, a theocratic monarchist and ultramontanist influenced by anti-liberal Catholic nationalist movements in France. Groulx and his contemporaries emphasized loyalty to the Pope over secular governments, and their influence was so strong that the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis embodied many of their beliefs.

Attempts to secularize education in the 1860s were thwarted, as the Catholic theocracy shut them down and restored control to the Church. Quebec remained a theocracy well into the 20th century, with the Catholic Church controlling public schooling and provincial healthcare until the 1960s. For much of its history, Quebecois culture saw itself as the last bastion of the traditionalist, Catholic, monarchist Ancien Régime of the fallen Bourbon monarchy. Liberal republicanism and the French Revolution were regarded as abominations, and French-Canadians believed they were the true French.

This mindset persists today, especially regarding Quebecois French. The 400-year-old dialect, rooted in Norman French and royal court French, is still regarded by many French-Canadians as “true French”. However, Europeans often deny this claim, pointing out the influence of anglicisms and the use of joual, a working-class dialect that was deliberately encouraged by Marxist intellectuals and separatists during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s to proletarianize the population.